Archeologist Uncovers Buried Bigfoot and Finds Out Truth About Them – Sasquatch Story

I still remember the moment we uncovered the skull. Massive, impossibly large, with features that were neither fully ape nor fully human. My team thought we’d made the discovery of the century. We had no idea that the grave’s occupant had family still living in those mountains—family who were watching us dig up their ancestors.

I’m an archaeologist, twelve years in the field, most of it spent wandering the Pacific Northwest in search of Native American artifacts or remnants of pioneer settlements. It’s honest work, usually routine: you dig, you catalog, you move on. Most days are uneventful. That’s how I like it.

Last summer, we were assigned to a site in remote Washington State, deep in the Cascades near the Canadian border. The area was so isolated we had to hike three miles from the trucks to reach our location. The forest there is dense, the kind of place where sunlight struggles to reach the ground even at noon.

Our goal was to search for traces of an expedition that vanished in the 1800s—a group of trappers and traders who supposedly disappeared without a trace. The first few days were normal. We set up camp, established our grid, and began the slow process of removing layers of soil and debris.

On our third day, one of the team members spotted something odd: a stone marker, two feet tall, covered in unusual carvings. The patterns didn’t match any Native American tribe in the region, and the placement seemed random. Over the next week, we found more markers, forming a rough circle thirty feet across. Each had similar carvings.

We thought we’d stumbled onto an undocumented cultural site. We started excavating inside the circle. The ground felt different—softer, disturbed more recently than the surrounding area. The soil had a looseness that suggested someone or something had dug here before.

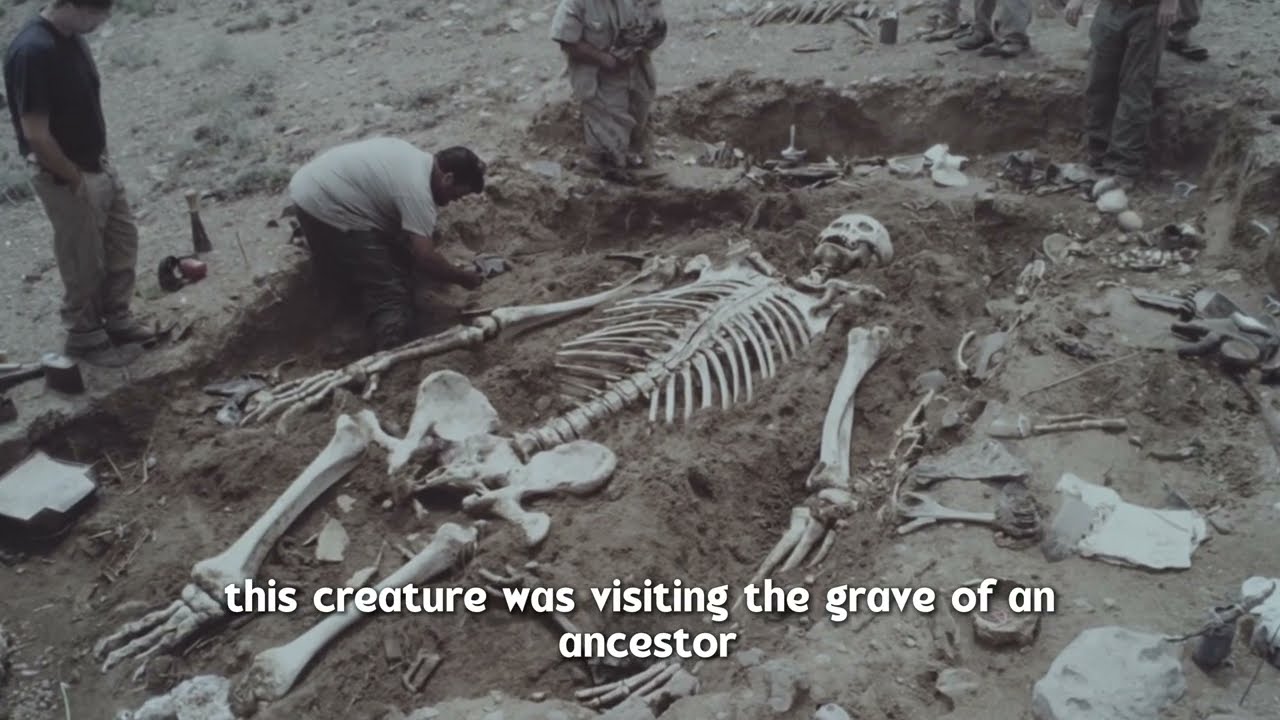

We proceeded carefully, documenting every inch as we went deeper. About two feet down, we struck something solid. At first, I thought it was a rock, but as we brushed away the dirt, I realized we were looking at bone. Big bone. Way too big to be human. The color was wrong—darker than typical human remains, and the density suggested significant age.

The team gathered around as we continued excavating. What emerged from that earth still gives me chills. It was a complete skeleton, but unlike anything I’d ever seen. The creature must have been eight feet tall when alive, maybe more. The femur alone measured over twenty inches, suggesting massive height and weight.

The skull was enormous, with a pronounced brow ridge creating deep eye sockets and a sagittal crest running along the top, like a natural mohawk of bone. The jaw was heavy, the teeth large, suited for an omnivorous diet. The pelvis was broad, designed for bipedal locomotion but with structural differences from humans. The rib cage was barrel-shaped, suggesting large lung capacity.

But what really caught my attention were the hands—enormous, twice the size of a human’s, with opposable thumbs and robust finger bones. The feet showed adaptations for walking on two legs, with pronounced arches and heelbones built for absorbing impact.

This wasn’t just some animal that died in the woods. The body had been positioned deliberately, laid out flat on its back with arms crossed over the chest—a pose suggesting reverence and care. There were objects buried with it, artifacts that spoke of ritual and meaning.

We found primitive stone tools shaped and placed near the hands, as if the deceased might need them in an afterlife. There were carved wooden pieces, most rotted beyond recognition, leaving only fragments and impressions in the soil. The surviving pieces showed sophisticated carving techniques, deliberate patterns and designs requiring skill and artistic vision. Scraps of woven plant fiber suggested the body had been wrapped in a burial shroud.

Small stones had been arranged in patterns around the body, forming geometric shapes whose meaning I could only guess at. Everything pointed to intentional burial, to ritual, to culture. Whatever this creature was, it belonged to a society that cared for its dead, that honored them with dignity and respect.

Nobody wanted to say it out loud, but we all knew what we were looking at. This was a Bigfoot—an actual, real Bigfoot that had lived and died centuries ago, buried by its own kind according to some ceremony or tradition.

I made the decision to keep this quiet. We documented everything with photographs and detailed notes, but I didn’t report it up the chain. Something told me we needed to understand what we had before bringing in officials. Call it intuition, call it caution—I just knew we weren’t ready to share this discovery.

The next day, we brought in ground-penetrating radar. What it showed was staggering. There weren’t just one or two burial sites. The radar indicated at least twelve distinct anomalies, all roughly the same size and depth, arranged in a pattern that suggested a cemetery or burial ground.

We were looking at evidence of a community that had used this place to bury their dead for who knows how long. Over the next two weeks, we carefully excavated three more sites. Each revealed similar findings. The bodies were positioned the same way, buried with personal objects and tools.

One grave contained what appeared to be a juvenile, maybe the equivalent of a human teenager. The skeleton was smaller, more delicate, buried with carved wooden objects that looked like toys. Another held an elderly individual, its bones showing signs of arthritis and old injuries, buried with an intricately carved walking stick.

Around each grave, we found evidence of fire pits—carefully arranged stones showing exposure to heat. Chemical analysis of the residue suggested they’d burned specific plants and herbs during ceremonies. These creatures hadn’t just dumped their dead in holes. They’d honored them, remembered them, mourned them.

The stone markers we’d found first turned out to be headstones, each carved uniquely, like signatures or family crests. This level of sophistication was mind-blowing. We weren’t looking at mindless apes or primitive beasts. We were looking at evidence of a species with complex social structures, symbolic thinking, and cultural traditions.

That’s when things started getting strange around camp.

It started small. One morning, I found our tools had been moved during the night. Nothing was damaged or stolen, just rearranged. Shovels I’d left in one spot were propped against a tree twenty feet away. The tarp covering one of the sites had been carefully folded and placed on a stump.

Then we found the footprints. Massive prints in the soft dirt near camp, each at least sixteen inches long, showing clear toe definition. They weren’t bear prints, and they sure as hell weren’t human. The prints led from the edge of camp into the dense forest, but none of us followed them. Something about those tracks made everyone nervous.

The feeling of being watched became constant. That prickle on the back of your neck when someone’s staring at you—we all felt it. Working at the dig sites, cooking dinner, even just sitting around the fire at night. Eyes were on us. I was sure of it.

One morning, a team member found fresh berries outside her tent, still on the branch, carefully placed on a flat rock. It felt like an offering, or maybe a message. At night, we started hearing vocalizations from the forest—not quite howls, more like long warbling calls that echoed through the trees. Sometimes they sounded almost like singing.

Multiple voices, different pitches, calling back and forth in the darkness. None of us slept well. The team wanted to leave. I didn’t blame them, but something kept me there—a need to understand what we’d found.

Against my better judgment, I convinced them to stay a few more days.

Then I met one of them face to face.

It was early morning, maybe an hour after sunrise. I was alone at the most recent burial site, double-checking measurements and taking photographs. The rest of the team was at camp, having breakfast. I was crouched down, examining some woven material we’d found near the skeleton’s hands, when I heard something move behind me.

I turned slowly. There it was—standing at the edge of the clearing, maybe twenty feet away. Massive, easily nine feet tall, covered head to toe in dark brown fur that looked thick and well-maintained, not matted or dirty. The fur caught the morning light, showing subtle variations in color from deep chocolate on the back to lighter auburn tones on the chest and face.

The shoulders were incredibly broad, supporting arms that hung down past the knees, hands that could have wrapped around my entire torso. The legs were thick and powerful, built for carrying immense weight over rough terrain. The face was simultaneously ape-like and eerily human—a flat nose, pronounced brow ridge, and a mouth capable of complex expressions.

But what struck me most were the eyes. Not blank animal eyes, but intelligent, aware, and filled with an emotion I recognized immediately: sadness. Deep, profound sadness that radiated from those eyes like heat from a fire.

The creature was mourning. I realized it was experiencing genuine grief for the ancient bones we’d disturbed. I froze. This being could have killed me without effort, and we both knew it. But it didn’t charge or threaten. It just stood there, looking at me, then at the excavated grave.

Slowly, deliberately, it walked forward. Each step was careful, almost hesitant. When it reached the edge of the excavation, it dropped to its knees with a gentleness that seemed impossible for something so large. Its enormous hands reached out and touched the ancient bones.

It made soft sounds, low vocalizations that came from deep in its chest. The sounds were mournful, unmistakably so. That’s when I understood: this wasn’t just some curious animal investigating strange activity in its territory. This creature was visiting the grave of an ancestor, a family member buried centuries ago. We had dug up its family cemetery, disturbed the resting places of its own kind.

The guilt hit me like a punch. The creature looked directly at me. There was no anger, no aggression—just grief and something like disappointment. It stayed there for several minutes, touching the bones, making those soft mourning sounds.

Then it stood, turned, and walked back into the forest, disappearing as if it had never been there.

That evening, I returned to the burial site alone, bringing food—dried fruit, nuts, jerky. I arranged it on a flat stone near the graves and sat down to wait, not sure what I expected.

As darkness fell, the creature returned. This time, it wasn’t alone. A second, slightly smaller individual accompanied it, probably female. They approached cautiously, watching me from the treeline before stepping into the clearing.

When they saw the food, they stopped. The larger one made low grunts and gestures to the female, who made sounds back. They came forward together and examined the offerings. The female picked up some dried fruit and sniffed it before eating a piece. The male took some nuts. They were cautious but not afraid, glancing at me as if trying to figure out my intentions.

Then the male did something that changed everything. He walked to the grave we’d excavated and pointed at the bones, then at the forest, gesturing back and forth. It was clear what he wanted: the remains covered again, returned to the earth where they belonged.

The female picked up one of the carved wooden objects we’d found, holding it to her chest in a gesture of tender reverence. These were family, ancestors, loved ones.

Without a word, I grabbed a shovel. The two creatures looked at me in surprise as I began scooping soil back into the excavation. After a moment, they joined me, using their massive hands to push dirt into the grave, working carefully to position everything back as it had been.

We worked together in silence, human and Bigfoot, side by side until the bones were covered again. When we finished, they placed the stone marker back in its original position, arranging rocks around it in a specific pattern.

Then the male reached out one massive hand and placed it gently on my shoulder—a gesture of acknowledgment, thanks, respect.

They left after that, vanishing into the darkness. I returned to camp and lay awake all night, thinking about what had happened.

The next morning, I found something outside my tent—a marker made from woven grass, intricately braided and tied with plant stems. More of them formed a trail leading away from camp into the forest. I told the team I was scouting for water and followed the trail alone.

It led deeper into the mountains, winding through valleys and over ridges. The markers continued for over a mile, always visible, always clear. Whoever had left them wanted to make sure I didn’t get lost.

The trail ended at a hidden valley, a place so remote I’d never have found it alone. The valley was a perfect natural amphitheater, surrounded by steep ridges, with a small stream running through the center.

There, spread out before me, was evidence of habitation that took my breath away. Shelters made from branches and leaves, arranged in a rough circle like the burial sites we’d found. Each shelter was different, customized for different family members or purposes. Built against windbreaks, using terrain for protection.

A fire pit sat in the center, lined with stones. The ashes were still warm. Drying racks held strips of fish and meat. The area showed signs of long-term use and thoughtful organization, but was currently empty, creating an eerie sense of having just missed the inhabitants.

I walked through the settlement carefully, not touching anything, just observing. More carved wooden objects lay scattered around—figurines of animals, tools, decorative pieces. Against one rock shelter, I found primitive artwork using natural pigments, depicting families, hunting scenes, ceremonies.

I was so absorbed in the paintings that I didn’t hear the creature approach. When I turned, the male from the previous night was standing at the edge of the settlement, watching me. He gestured for me to follow, leading me deeper into the valley to a cave entrance, partially hidden by vines. He pulled the vines aside and waited for me to enter.

Inside, the cave walls were covered in paintings—hundreds, maybe thousands. This was the history of their kind, recorded in images and symbols spanning centuries or millennia. The oldest paintings near the back showed larger communities, groups hunting massive animals now extinct. Families gathered around fires, ceremonies under full moons.

The images progressed forward in time toward the entrance, telling a story. There were paintings of humans appearing in their territory, small figures with weapons depicted in stark contrast to the larger forms. Conflict, violence, a turning point in their history.

Then the paintings changed, showing the creatures fleeing, hiding in the deepest forests and highest mountains, living in smaller groups, becoming more secretive with each generation.

The most recent paintings near the entrance showed solitary families living in isolated valleys, always watching, always hiding, always aware of the human presence that threatened their existence.

The male pointed to an image of his kind concealing themselves in dense forest, then pointed at himself. He showed me a painting of humans with guns and spears, then made a pushing away gesture. I understood. They had chosen isolation to survive, to avoid conflict.

He let me examine the cave paintings as long as I wanted. When I turned to leave, he stopped me with a gentle gesture and led me to another part of the valley. We emerged into a clearing where the rest of the family was waiting—the female I’d met before, two younger ones, and an elderly individual grizzled with age.

The juveniles were curious but shy, peeking out from behind the adults. The female approached carrying a wooden bowl of water, offering it to me. I drank, grateful for the gesture—a sign of hospitality, kindness, friendship.

The elderly one came forward, extending a massive hand to touch my face with delicate curiosity. The family sat in a circle and gestured for me to join them. We shared food—berries, root vegetables, dried fish, mushrooms cooked over the fire.

As we ate, I observed their manners. They ate slowly, deliberately, sharing portions equally, adults ensuring the young got enough. The elderly ate smallest portions, the others gently pressing more food on the old one when they thought no one was watching.

The juveniles eventually overcame their shyness, approaching with growing confidence and curiosity. They touched my clothes, tugged gently at my hair, compared their hands to mine, showed me carved wooden animals and collections of interesting stones.

These interactions revealed so much about their intelligence and emotional depth. They were capable of play, pride in possessions, the desire to share. In the most fundamental ways, they were just like human children.

Over the next days, I returned to the valley again and again. Each time, the family showed me more of their world—fishing in streams, gathering plants, making tools, preparing bodies for burial, carving marker stones, demonstrating healing practices.

They took me to a sacred grove where they marked seasonal changes, the ground worn smooth from generations of feet. Stone arrangements marked positions for ceremonies. I couldn’t understand the rituals completely, but I could feel their importance.

What struck me most was the realization that they had chosen this life deliberately. They weren’t primitive creatures lacking intelligence. They developed a parallel culture, prioritizing harmony with nature over technological progress. They lived sustainably, took only what they needed, moved with the seasons, maintained traditions connecting them to ancestors and environment.

Their society was sophisticated, just different in its priorities.

Then everything changed.

One morning, I arrived at the valley to find the family agitated, making distressed vocalizations. The male grabbed my arm, pulling me toward the ridge overlooking our dig site. More people had arrived—officials, heavy equipment, vehicles. Someone had reported our findings.

The authorities were going to expand the excavation, dig up all the graves, turn the cemetery into a full-scale operation. The family was distressed. The male looked at me with pleading eyes, gesturing toward the burial sites, then the forest. The female held a young one close, comforting it as it cried.

The family retreated into the forest quickly, disappearing before anyone at the dig site could see them.

I stood there, watching the people below prepare to disturb more graves. I had to make a choice—the biggest of my life.

I hiked down to the site, trying to look casual. The team was excited, talking about the discovery, the research. Someone had brought champagne.

I smiled and nodded, but my mind was racing, thinking about the family, their grief, the trust they’d shown me. If I let the excavation proceed, what would happen? The area would be swarmed with researchers, media, tourists. The family would lose their home, their privacy, their way of life. They’d become specimens, objects of study.

That evening, back at my tent, I found something that made my decision final—a carved wooden figure, small enough to fit in my palm, showing a Bigfoot and a human standing side by side, hands touching. A gift, a sign of trust, friendship, coexistence.

I waited until everyone was asleep. Then I went to work, moving quietly in the darkness. I spent the night restoring the graves, returning every artifact, covering the bones, replacing the markers. I destroyed all evidence—deleted photographs, burned notes, corrupted radar data, fabricated reports suggesting the remains were bear bones misidentified due to preservation.

I wrote up geological reports indicating the site was unstable, convincing enough to force evacuation. When the officials arrived, I presented my findings. The graves were gone, the data corrupted, the report suggested immediate evacuation. They had no choice but to shut down the operation.

My reputation took a hit. I was removed from the project, faced a formal review. I accepted all of it without complaint. Some things are more important than professional success.

A week later, after everyone had left and the site was abandoned, I returned one last time. The family was waiting, standing among the restored graves. The male walked forward, placing both hands on my shoulders, holding my gaze. I saw gratitude, respect, love.

The female approached, carrying a pendant carved from wood, strung on braided cord. She placed it around my neck—a symbol of friendship.

The elderly one touched my forehead—a blessing.

The juveniles hugged my legs, their arms wrapping around me. The family led me to the cave one final time. They showed me a new painting—still wet—depicting a human helping cover graves, then standing with the family in a circle, wearing a pendant.

I’d been added to their history, recorded as a friend and protector.

We stood together in that cave for a long time, seven souls who understood something most never would: that some relationships matter more than evidence, that some secrets are worth keeping.

When it was time to leave, the family walked me to the edge of their valley, removing the woven markers as we passed so no one else could follow. At the boundary, the male raised a hand in farewell. The others waved, copying the gesture. The elderly one touched its chest, then pointed at me, then the forest—a sign that I would always be welcome.

I watched them fade into the trees, becoming shadows, then nothing. The forest closed around them like a curtain.

That was six months ago. My career recovered somewhat, though I’ll never work on a high-profile project again. I’m okay with that. I transferred to a different region, work on smaller digs. I keep the pendant hidden, only taking it out when I’m alone. It’s the only proof I have.

Sometimes I wonder if I did the right thing, destroying all that evidence. Then I remember the young one crying, the elderly one’s blessing, the male’s hands on my shoulders. I know I made the only choice I could live with.

I think about the family often, hoping they’re safe and undisturbed. Sometimes, at remote sites, I find small carved objects left in unusual places—a figurine in a tree hollow, a decorative piece on a rock. Signs that I recognize, reminders that I’m not forgotten.

Every few months, I see news reports of sightings. Blurry photos, footprints found by hikers. Most people dismiss them as hoaxes. I just smile and say nothing.

Some discoveries aren’t meant to be shared with the world. Some truths are too precious, too fragile, too important to expose. The family chose isolation to survive, and I chose to protect that isolation.

I gave up recognition to honor their trust. I’d do it again. Their trust is worth more than any career achievement. Their friendship is more valuable than any discovery.

And so they remain hidden. Their existence unproven, their culture undocumented, their history known only to themselves and a handful of humans who earned their trust.

That’s how it should be. The truth isn’t meant for everyone. It’s meant for those rare few who understand that proof isn’t always the same as truth, and that sometimes the greatest discoveries are the ones we choose not to share.

I uncovered the cemetery. I met a living family. I learned their secrets and earned their trust. And then I buried it all again, so they could continue in peace.

That’s my story. That’s my choice. And that’s a decision I’ll defend until the day I die.

The Bigfoots are real. I know it. They know it. And that’s all that matters.