FBI Agent Interrogated a Mermaid. Her Revelation About Humanity Is Terrifying

I am Dr. Ellen Marsh, and for 23 years, I have kept silent about what happened in the deep waters off the Great Barrier Reef in April 2001. I was a marine biologist, my life devoted to coral reefs, fish population dynamics, and the intricate balance of underwater ecosystems. I taught at James Cook University, led research expeditions, and published papers on the health of the ocean. All of that ended the night our research vessel’s holding tank became home to something that should not have existed—and looked at me with eyes that understood exactly what I had done.

This is not a story about folklore or fantasy. It is a record, drawn from research logs, dive records, and the memories of those who were there. The footage, photographs, and physical evidence disappeared within 72 hours of our return to port, along with any official acknowledgment that our expedition ever happened. But I was there. I saw her. And she changed everything I believed about the ocean—and about myself.

The Vanishing

On March 28, 2001, the Australian Maritime Safety Authority contacted me. Seven divers had vanished from the waters near Osprey Reef over three months. Osprey is remote, accessible only by live-aboard vessels, and its eastern wall plunges into deep water—a magnet for experienced technical divers.

The first disappearance was Marcus Chen, a seasoned instructor from Sydney. He signaled he was fine, swam around a coral outcropping, and was never seen again. No body, no equipment, no trace. The second incident involved a married couple, diving together. Their computers flatlined simultaneously at 38 meters. By March, three more divers had vanished, all in the same zone.

The Water Police found nothing—no shark attacks, no equipment failures, no bodies. The currents were not strong enough to sweep divers away, and there was no evidence of predation. The official theory was equipment failure and down currents, but I had reviewed the data: the descents were controlled, the disappearances sudden, clustered in a 12-square-mile zone.

They called me because I knew those waters. I had mapped the reef, tracked migrations, and dived that wall dozens of times. I had never seen anything that explained seven people vanishing without a trace.

The Investigation

I recommended a week-long research expedition: underwater cameras, sonar mapping, systematic documentation of marine activity. The authority approved funding for a vessel, equipment, and a small team. They wanted answers before the tourist season brought more divers.

On April 2, I boarded the Meridian—a 68-foot catamaran equipped with dive compressors, camera sleds, sonar arrays, and a 2,000-liter seawater holding tank. The crew included Captain Ray Thompson, two graduate students (David Ortiz and Sarah Kim), and a documentary crew led by Alex Chen, whose company provided our camera equipment in exchange for filming the expedition.

We left Cairns Harbor at dawn. The sea was calm, the weather clear. By mid-afternoon, we anchored near the eastern wall, where the disappearances had occurred. My preliminary dive revealed a healthy reef, dense coral, normal fish populations. But Ray noticed something I missed: no dolphins, no turtles. Osprey Reef was famous for both. Thirty years, Ray said, and he’d never seen it so empty. Something had spooked the big animals.

The First Clues

The next day, we deployed six underwater cameras along the wall, each spaced about 50 meters apart, aimed outward toward the open ocean. If something was pulling divers away, we hoped to catch it on video. The cameras had motion sensors and low-light capability.

Alex, ever the documentarian, speculated about rogue predators. I told him the odds of a new large species in these waters were nearly zero. But seven experienced divers do not vanish because of environmental factors. Not from the same place, not without evidence.

When we retrieved the first batch of footage, four cameras had malfunctioned. The recording systems simply stopped during the night. The two that worked showed normal reef life—sharks, groupers, barracuda. No sign of anything unusual. The electronics showed no water intrusion, no damage. Sarah suggested electromagnetic interference, but nothing else on the boat was affected.

We redeployed the cameras with extra shielding, clustering them tighter in the sector where most disappearances had occurred.

The Encounter

On April 6, at 11:30 p.m., Alex came to me with footage. One camera had captured something at 3:47 a.m., moments before it failed. The clip was brief: a shape glided past the edge of the frame, too large for a shark, wrong for a grouper. It was humanoid. An arm, fingers spread, moved with intention. Could be a diver, Alex said. But we were alone out there.

David thought it might be a large ray. Sarah suggested a dolphin, but we hadn’t seen any dolphins all week. Ray watched the footage once, then walked away.

The next afternoon, Alex proposed baiting whatever was down there. We had frozen tuna on board. Ray reluctantly agreed. I should have objected, but the footage haunted me. One night, I said. We run the bait line tonight. If nothing happens, we leave.

The Haul

We prepared the bait line, mixing tuna blood with seawater and running heavy test line off the stern, sinking it to 25 meters. The documentary crew had night vision cameras ready. At 11:30 p.m., nothing had happened. The line hung slack. Then Ray stood up. The line was moving—steady, strong, not the sharp strike of a shark.

We hauled in the line, gaining a meter at a time. The resistance was dead weight, with occasional surges. The boat lurched to port. I called to cut the line, fearing we’d capsize, but Ray insisted. Five more meters. Let’s see what we’ve got.

Suddenly, the resistance stopped. The line went slack, then taut again, lighter now. It was coming up. The water churned, shapes breaking the surface. Ray shouted for the net. Together, we hauled up a reinforced mesh net, pulling it over the rail and onto the deck.

There, tangled in the net, was something humanoid—about six feet long, gray-blue skin, elongated torso, webbed fingers, fused tail structure. The face was human enough to be recognizable, alien enough to be wrong: large, dark eyes, no visible nose, a mouth too wide. The skull was elongated, hydrodynamic.

She opened her eyes and looked at me. I saw intelligence, awareness, and rage.

The Dilemma

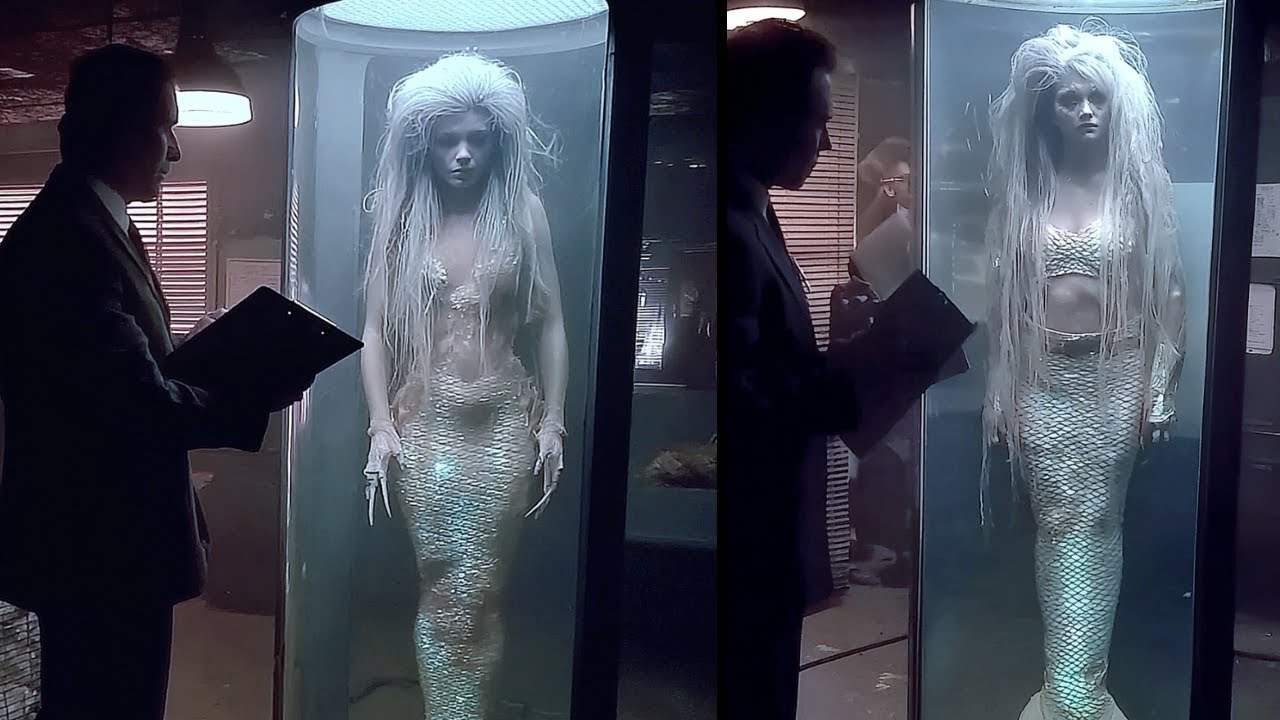

Ray threw a tarp over her and ordered us to move her to the holding tank. We dragged her across the deck, still tangled in the net, and lowered her into the seawater tank. She freed herself from the mesh, then floated upright, staring out at us through the reinforced viewing port.

Ray turned to Alex: whatever you filmed, it doesn’t exist. Alex nodded, but I knew the footage was already backed up and distributed.

Sarah came up on deck, pale. “Aquatic humanoids, convergent evolution to that degree… It’s not possible.” David said, “It’s in the tank. Seems pretty possible to me.”

I knelt by the viewing port. She watched me. Not aggressive, not fearful—just watching.

What do we do now? Sarah asked. I should have said release her immediately. Instead, I said, “We keep her for 24 hours. We document everything. Then we decide.” That decision still wakes me at night.

The Watch

None of us slept. Ray took the first watch, sitting beside the tank. Alex uploaded his footage to encrypted cloud storage. I warned everyone: no external communication until we were back in port. No radio, no satellite internet. If word got out, we wouldn’t decide what happened next.

At 4:30 a.m., I went on deck. She hadn’t moved, just floated, watching. Up close, her skin showed subtle patterns—darker patches on her sides and back, lighter along her front. Her hands rested at her sides, webbing between fingers translucent.

Ray told me stories—old tales from islanders about things in the deep water that looked like people but weren’t. Equipment failures, beached whales, dolphins that no longer came to Osprey Reef. “We caught someone, not something,” Ray said. “And we need to decide if we’re the kind of people who keep someone in a cage.”

The Attempt

Alex wanted to try communication. He played dolphin vocalizations through the underwater speaker. She responded instantly—clicks and low-frequency tones, her body language alert. Alex knocked on the glass; she matched his rhythm exactly. She was responding, not just mimicking.

Alex tried hand signals, speech, writing words on a whiteboard—nothing. But when he played dolphin sounds, she responded with structured vocalizations. When he played sonar pings, she moved to the back of the tank, defensive, emitting sharp sounds.

Sarah analyzed the recordings. “These vocalizations have syntax. Not just noise.” We tried showing her images—fish, sharks, dolphins. She leaned closer to the glass when she saw the dolphin.

The Realization

I stayed by the tank as the sun rose, thinking about the missing divers. Seven disappearances, all in the same zone, all experienced, all without a trace. I wondered what I had dismissed as folklore that might have been observation.

Ray brought coffee. “Why you?” he asked. “She keeps watching you.” I didn’t have an answer. Maybe I was the first face she saw, maybe she recognized I made the decision to keep her.

Ray told me about a night dive in New Caledonia decades earlier—seeing something with hands swimming away into the dark. “We’re going to tell ourselves this is science, but that’s not what this is. We caught someone, not something.”

The Choice

Alex wanted to build a communication system, assign meanings to sounds, teach her to respond to questions. But Sarah said it would take months, not hours. We tried showing her more images—familiar fish, sharks, dolphins. She responded only to the dolphin.

The tank was too small. She hovered in place, unable to swim, unable to do anything but watch us. I realized then that the ethical dilemma was not about discovery—it was about responsibility. We had a choice: compassion or curiosity.

I looked at her through the glass, remembering the missing divers, the stories Ray had told, the silence of the dolphins. I understood that some mysteries are not meant to be solved, and some boundaries are not meant to be crossed.

Epilogue: The Ocean’s Secret

We documented everything we could. But in the end, the footage, the evidence, the creature herself—all disappeared. The official record of our expedition was erased, the story buried beneath bureaucracy and fear.

But I was there. I saw her. I made the choice. And I carry the memory of her eyes—watching, understanding, forgiving, or perhaps just waiting for us to realize that the ocean is more than a resource, more than a place to explore. It is a world with its own secrets, its own sentinels, and its own stories.

If you ever dive the eastern wall of Osprey Reef, remember what the ocean keeps hidden. Remember the silence of the dolphins, the stories of the islanders, and the eyes that watched from the deep. Some mysteries are not meant to be solved, but to be respected. And sometimes, the greatest discovery is knowing when to let go.