He Found Out What Mermaids Do to People Who Sink Too Deep… The Truth Is Horrifying

My name is David Torrance. I’m 56 years old, and I haven’t been in the water since March 2001—not a pool, not a bathtub deep enough to submerge my head, not even the ocean I can see from my apartment window in San Diego. People who knew me before find this strange. I was a deep-sea salvage diver for 18 years, certified to a thousand feet, comfortable in environments that would kill most people in seconds. I loved the work, the pressure, the darkness, the silence of the deep. That was before the Philippine Trench. Before I learned what’s really down there.

I’m telling this story now because Marcus Chen resurfaced three weeks ago—not physically, but in a way that forced me to confront the past. Marcus has been in the Columbia Psychiatric Institute in Portland since May 2001, the same locked ward, the same room. But something changed recently. The nurses called me because I’m listed as his emergency contact, the only member of our old crew who still visits. When I arrived, Marcus was sitting by the window, lucid for the first time in 23 years. He looked at me with clear eyes and said five words: “They’re coming up, David. Deeper.” I don’t know what that means. I don’t know if Marcus is truly lucid or if this is another break from reality, but those words, combined with the three fishing vessels that vanished off Mindanao last month, tell me it’s time people knew the truth.

The Descent

The job came through in February 2001. A Liberian-flagged cargo vessel, the Celeste Maritime, had gone down 40 nautical miles northeast of Mindanao in the Philippines. Standard salvage operation, decent pay, three-week contract. Our team of five had worked together for four years at Pacific Deep Recovery. We knew each other’s rhythms, trusted each other’s skills. Marcus Chen was our primary diver, ex-Navy salvage specialist. Jennifer Oaks, our secondary diver, the best technical diver I’d ever worked with. Thomas Ruiz handled topside operations and dive medicine. I was the documentation specialist, managing cameras, sonar, and sample collection. Peter Halifax was dive supervisor, running operations with rigid adherence to safety protocols.

We flew into Davao on February 23 and spent three days on equipment checks. The Celeste Maritime had gone down in 890 feet of water, on the edge of the Philippine Trench. The trench itself dropped to over 34,000 feet just 15 miles east, creating unusual current patterns. Our initial sonar surveys showed the ship intact on the bottom, listing 30 degrees to port. We mapped the debris field and calculated our gas requirements.

The first two days of diving went perfectly. Marcus and Jennifer made four dives each, documenting the wreck’s exterior. No collision damage, no evidence of fire or explosion, no hull breach. Whatever sank the Celeste Maritime happened inside.

On March 2, I went down with Marcus for my first dive on the wreck. Surface conditions were ideal. We descended at 75 feet per minute, the standard rate. At 200 feet, the light began to fade. By 400 feet, we were in twilight. At 600 feet, we switched on our primary lights. That’s when I first noticed something wrong with the sonar returns—irregular formations arranged in concentric circles extending away from the wreck. I signaled Marcus, pointed to my display. He responded: “Seeing it too. Probably volcanic basalt columns.” But at 750 feet, my lights picked up the first of the formations. Not basalt, not rock. Coral at first glance, but the color was wrong—pale white and gray, and the shapes too regular, too familiar.

I swam closer. The coral branches were bones, human bones, ribs, femurs, arm bones, arranged in deliberate patterns like some underwater garden. Dozens of skeletons, maybe hundreds, some still partially articulated. My breathing rate spiked. Marcus’ voice was steady but strained. “We’ve found human remains, multiple individuals, extensive arrangement. Requesting permission to document and continue.” Peter’s voice from the surface: “Document thoroughly. Continue to wreck site. Bottom time now, 18 minutes remaining.”

I began filming. The formations extended in all directions beyond our light range. Some skeletons were old, encrusted with marine growth, but others were newer, still ivory white, some with fragments of clothing attached—a diving mask, a watch, a wedding ring. Then we heard the sound, not through the water, but through the comm system itself. It started as a low-frequency tone, then rose in pitch and complexity. Whale song, but fragmented, mixed with something else—syllables, words spoken underwater by something without human vocal anatomy.

Peter’s response: “Negative. No broadcast from surface. You’re on a closed frequency.” The sound continued, rising and falling in patterns that felt conversational. My depth gauge read 782 feet. My remaining bottom time was 14 minutes. Marcus made the hand signal for abort dive just as my light picked up something moving at the edge of visibility. Something large, something deliberate. For just a moment, caught in my light beam, I saw pale skin, translucent, and a face that was watching us with focused intelligence. Then my camera died. The last frame showed a shape my brain still struggles to process—two large eyes, webbed hands reaching toward us through the dark water.

Marcus grabbed my arm. “We’re going up now.” The ascent should have taken five hours and forty minutes. We made it in four hours and fifty-two minutes, cutting decompression stops as short as protocol allowed. Every minute hanging at our safety stops, suspended in dark water with that sound still broadcasting, felt like an eternity.

The Aftermath

Peter was furious when we surfaced. “You could have bent yourselves. Whatever spooked you down there doesn’t justify risking decompression sickness.” He was right. In technical diving, panic kills more people than equipment failure. But Marcus and I had both felt the same overwhelming need to get away from that depth.

We were in the decompression chamber within 20 minutes, breathing pure oxygen for six hours. Thomas monitored us. No symptoms appeared, but those hours gave me time to think about what I’d seen. Jennifer and Peter reviewed our dive logs. The bone formations showed clearly on sonar—irregular structures extending 300 feet from the wreck, but there was no record of mass casualty events in this area, no sunken ships that would account for hundreds of bodies.

Our camera equipment shut down at 782 feet. No water intrusion, no electrical fault. The recording media was intact, but the files were corrupted. Thomas had recorded the sound from the surface. The bass frequency matched humpback whale vocalizations, but there was something else—high-frequency components that didn’t match any catalogued marine mammal. Patterns that looked almost like speech phonemes, but distorted.

Jennifer was examining the sonar logs. “These formations aren’t random. Look at the spacing. Concentric rings, each about forty feet apart. That’s not natural.” Marcus had been quiet since emerging. “The remains aren’t all Filipino. I saw diving equipment, modern gear. And the arrangement isn’t ceremonial. It’s functional, like a garden plot, like something is cultivating them.”

The word “cultivating” hung in the air. Peter made the decision: “We’re documenting this and reporting it. Recovery is suspended until authorities clear the site.”

The Return

That should have been the end of it. But Jennifer noticed something we’d missed. The cargo holds were open. “Someone already accessed this wreck recently.” Peter studied the screen. “No other salvage operation in this area. We’re the only team with permits.” Jennifer: “Someone else was here first, and they went inside the wreck.”

The decision to make one more dive was probably the worst mistake of my life. Marcus volunteered to go down alone—a quick survey of the cargo holds, 15 minutes of bottom time. Jennifer would be his backup at 400 feet. I would manage communications.

Marcus descended at 1,400 hours. His voice came through clear at each depth check. At 850 feet, he reached the wreck. “Cargo hold accessed. Hatch covers removed from inside. Someone cut through the locking mechanism. Entering hold now.” There was a long pause. Then: “Jesus Christ. Report.” Peter said immediately. “The cargo. It’s not what the manifest said. These aren’t containers. They’re cages. Steel cages. Maybe twenty of them. All open. Whatever was inside is gone.”

My skin went cold. “Marcus, get out of there.” “Wait, there’s something written on the bulkhead. Coordinates and a date. December 1987. It says, ‘They took all of them. God forgive us.’”

The sonar display erupted with new returns—dozens moving up from deeper water, ascending at impossible speeds, converging on Marcus’ position. “Marcus, you have multiple fast movers approaching. Emergency ascent.” Marcus’ breathing rate spiked. “I see them. There are dozens. They’re surrounding the wreck. They’re not fish.” Through the comm system, I heard that sound again, louder now, coming from multiple sources, and underneath it a rhythm that sounded like speech.

Jennifer descended to 600 feet. “I have visual. Multiple lights, but they’re not Marcus’ lights. They’re bioluminescent, moving around the cargo hold.” Marcus’ voice was wrong—too calm, too distant. “I understand now. They’ve been taking them for so long. The cages…”

His vital signs dropped below consciousness threshold. On the sonar, I watched his return descend, not rising toward Jennifer, but sinking deeper, pulled down by the shapes that had surrounded him. Jennifer tried to follow, but Peter ordered her to abort at 720 feet. We listened to Marcus’ regulator for eight minutes—regular breathing, then silence as he passed beyond communication range. The sonar tracked him to 1,400 feet before we lost the return. Marcus had descended into the Philippine Trench, surrounded by things that shouldn’t exist, and we had no way to follow.

The Mystery

Below 120 feet, the pressure is so intense that human physiology simply can’t function. Marcus should have died within minutes, but we’d heard him breathing. For eight minutes after he’d descended past the depth where human life is possible.

Thomas insisted we maintain station. “If there’s any chance he’s alive, we need to be here when he surfaces.” So, we stayed. Jennifer and I took turns monitoring sonar. Peter filed a preliminary report, omitting details about what Marcus had seen. The official report stated only that a diver had experienced probable nitrogen narcosis and descended beyond safe limits.

The authorities told us to maintain position and await a Coast Guard vessel, ordered us not to conduct further diving. We reviewed everything—audio, sonar, corrupted footage. The patterns were undeniable. The shapes moved with coordination, with purpose.

Jennifer found something in historical records: in December 1987, a Philippine Navy patrol boat disappeared in this area. Seven crew members, no wreckage. Three months before, a fishing vessel reported seeing lights, bioluminescent displays moving in organized patterns, and hearing singing from underwater. The Navy sent a patrol boat to investigate. It never came back.

The cargo manifest for the Celeste Maritime listed eight crew, but harbor records showed sixteen people boarded—eight crew and eight undocumented passengers. The cages were full when the ship went down. Whatever was down there knew the ship was coming. They were retrieving what had been delivered.

The Return

Thirty-one hours after Marcus disappeared, the sonar alarm triggered a single return ascending from deep water, taking a decompression profile that suggested controlled ascent. We watched the return climb, stopping at regular intervals for gas elimination. At 400 feet, Jennifer suited up. “If that’s Marcus, he’ll need assistance.” She descended to 300 feet and held position.

Her voice came through, grief mixed with horror. “I have visual. It’s Marcus. He’s alive. He’s ascending on his own power. But his eyes are open, and he’s not breathing from his regulator. He’s just ascending, like the pressure doesn’t affect him anymore.”

We brought Marcus aboard just before dawn. He’d been underwater for 61 hours. His skin was pale, translucent, blood vessels visible in patterns that seemed wrong. His eyes were open, pupils dilated, unresponsive to light. He was breathing, but slowly; his heart rate was 22 beats per minute. His body temperature was 88°. He should have been dead, but he was moving, standing, his eyes tracking movement.

He spoke. His voice was wrong. “They wanted me to tell you. The gardens are full. Hundreds of them. Thousands. Kept alive at depths where light doesn’t reach. Fed by minerals from thermal vents. Maintained in suspension between consciousness and death. Some have been there since the war. The second one. The ships that went down and were never found. The crews that vanished. They’re all there, all still aware, all waiting.”

Thomas tried to examine him, but Marcus wouldn’t let anyone touch him. He stood on the deck, water streaming from his suit. Then he spoke again: “I’m not Marcus anymore. Not completely. They changed something when they took me down. Showed me things. Put something in me that lets me survive the pressure. I could go back down right now. Descend to 2,000 feet without equipment, live there, join the garden.”

Jennifer asked, “Why keep people alive down there?” Marcus’ eyes fixed on her. “Because they’re lonely. Because they’ve been alone in the deep for so long, longer than humans have had language. They remember us. When we lived in the water together. They want us back.”

He stepped toward the rail, toward the dark water. Peter moved to block him, but Marcus was faster. He vaulted the rail and dropped into the ocean, disappearing without a sound.

The Warning

Marcus wasn’t dead. Nineteen days after he went back into the water, he surfaced near a fishing boat. The fisherman found him floating, conscious, his skin even paler. He was taken to a hospital, but doctors couldn’t explain his condition. His blood chemistry was wrong. Lung capacity tripled. Eyes adapted to process light in spectrums humans don’t see. He couldn’t speak, only made sounds resembling the vocalizations we’d heard.

Transferred to the psychiatric institute in Portland, Marcus sat in that room for 23 years, occasionally making those sounds. But three weeks ago, he spoke: “They’re coming up, moving to shallower water, adapting to depths where humans dive. The gardens are full and they need more. They’ve learned to change people faster now. The process that took 19 days with me takes only hours now.”

Three fishing boats vanished off Mindanao last month, in the same area where the Celeste Maritime went down. The recovery operation found one boat at 600 feet, cargo hold accessed from the inside. The Philippine Navy quietly established an exclusion zone around the trench.

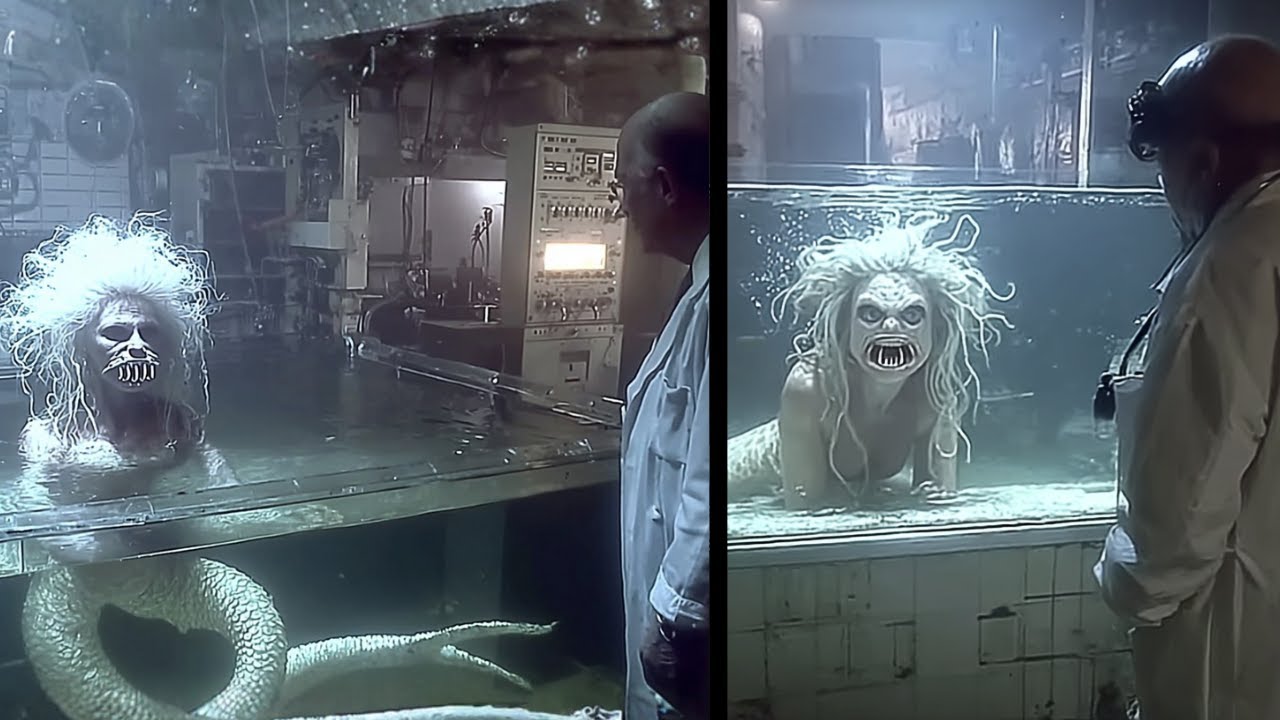

I still have the corrupted footage from my camera. You can see them if you know what to look for—pale shapes moving through darkness, faces almost human, eyes too large, hands webbed and elongated. You can see the gardens Marcus described: rows of figures suspended in water, attached to formations, bodies modified to survive without surface air, minds kept conscious through mechanisms I can’t understand.

Marcus was lucky. They let him go, changed him and sent him back as a message, a warning or an invitation. The others weren’t given that choice. They’re still down there, aware, waiting in the crushing darkness.

The Network

I didn’t tell anyone the full story for two years. I filed reports, attended debriefings, gave the sanitized version—equipment failure, probable nitrogen narcosis, tragic accident. Pacific Deep Recovery dissolved six months after we lost Marcus. Peter retired and moved to Arizona. Thomas took a position teaching hyperbaric medicine. Jennifer disappeared, moving to Costa Rica, living away from water.

I couldn’t let it go. I spent years researching maritime disappearances, cross-referencing dive accidents near trench zones. I found 47 cases—no bodies, no equipment, all at depths between 600 and 900 feet, all reporting unusual sonar readings or strange vocalizations.

I was contacted by others—divers who’d seen things they couldn’t explain, salvage operators in Japan, oil workers in the North Sea. Soviet research teams, French expeditions, all with similar accounts. Governments have known. Companies have known. I think we were sent there deliberately. Someone wanted us to find what we found.

Jennifer and I agreed to go back, to document it properly. We prepared equipment, tested systems, made arrangements for footage release if we didn’t return. In March 2024, we met Marcus in Davao. He was changed, his skin translucent, his eyes reflective. He showed us equipment from the deep—biological suits, organic rebreathers, crystalline cameras.

We descended together, passing bone formations, reaching the wreck, entering the gardens. Living people, suspended, modified, conscious. The deep ones surrounded us, pale shapes with massive eyes and elongated hands. They led us to the source—a massive organic structure maintaining the gardens, keeping the humans alive.

We saw Peter Halifax, our old supervisor, suspended near the entrance, changed but aware. Jennifer tried to free him, but Marcus stopped her. “Without the system, they’d die. The pressure would crush what’s left.”

The Choice

We surfaced after two hours. The footage we captured was corrupted, except for what was stored in the biological cameras. Marcus warned us: releasing this footage would make us targets. The modified ones on the surface would try to stop us.

We tried. We built a website, contacted journalists, prepared simultaneous releases. Then Thomas Ruiz drowned in his swimming pool. Jennifer disappeared. I knew they’d taken her, brought her back to the gardens. I was next.

Marcus visited me one last time. “They’re coming for you tonight. You can hide or you can tell this story. Put it somewhere it can’t be erased. Eventually, someone will understand.”

I received the original biological storage from Marcus’ daughter. Six months after Marcus returned to the ocean, the first cruise ship vanished—2,400 people, no distress call, no debris. The harvest had accelerated. Mass collection had begun.

I tried to warn people. Most dismissed me. A few believed but felt powerless. We formed a network, tracking patterns, documenting modified ones in authority. Investigations were shut down, evidence disappeared.

Epilogue: The Deep Ones

The conspiracy theorists were right. There was a plan to return humanity to the ocean. In October 2024, I received a package—a crystalline storage unit. Inside was footage of Jennifer suspended in a garden, her body modified, her eyes aware. A message appeared: “The gardens are full. The signal comes soon. You can warn them or you can join them. Choose.”

I’m making my choice now. I’m telling this story to anyone who will listen, putting it in places where it can’t be erased. Because soon, ships will disappear in numbers that can’t be ignored. And when that happens, this document will exist. The gardens are full. They’re preparing to expand. Every person who goes into deep water, every ship that crosses a trench, every submarine that descends, is at risk of being collected, modified, kept conscious for a life they didn’t choose.

I haven’t been in the water since 2001. I know they’re coming for me eventually. Marcus said they’ll take me last, so I can see how it unfolds.

Sometimes I dream about the gardens—about Jennifer and Peter and Thomas, suspended in the dark, conscious, waiting, part of something older than humanity, something that remembers when we lived in the ocean, something that wants us back. I wonder if they’re suffering, or if they’ve learned to thrive in darkness. I don’t know. And I’m afraid I’ll find out soon.