He Kept a Mermaid Hidden in His Basement for 40 Years — Until the Navy Found Out

My name is Dr. Robert Henley. I am 68 years old, and for four decades, I have carried a secret that shaped and shadowed my entire life. I was once a marine biologist, specializing in cetacean communication at the University of Maine. I published papers, advised fishing companies, and consulted for NOAA. I had a career, a reputation, and colleagues who respected my work. But that person ceased to exist the night I chose protection over truth. For forty years, I told myself I was saving a life. Now, I’m not sure. This is my story, and I need to tell it exactly as it happened—because the truth about what lives in our oceans is stranger than anything you’ve imagined.

The Night of the Storm

September 11, 1984. Hurricane Diana was bearing down on the Maine coast, winds howling at 115 mph. I was 28, living alone in my grandfather’s house on a rocky point outside Booth Bay Harbor. The house was perched on granite ledge and scrub pine, isolated enough that my nearest neighbor lived half a mile away. My grandfather, a retired ship captain, had left me the property six months earlier. His eccentric legacy included a saltwater pool built into the basement, fed by tidal channels he’d blasted through the bedrock. The water cycled naturally with the tides, cold and clean.

I’d repurposed the pool for research, installing hydrophones and monitoring marine mammal activity along the coast. It was perfect for someone who preferred solitude and didn’t mind isolation.

The hurricane hit at 9 p.m. I spent the evening listening to weather reports on a battery radio, eating cold soup straight from the can. The wind sounded like freight trains passing overhead. Around midnight, the eye passed over—sudden silence after hours of noise. I knew I had maybe forty minutes before the storm returned, so I went outside to check for damage.

The destruction was extensive: shingles torn off the barn, trees down across the driveway, the dock reduced to splinters. I walked down to the tidal pools with my flashlight, checking the channels that fed the basement pool. That’s when I heard it—a sound unlike anything I’d ever heard. Not quite singing, not quite clicking. Something between a dolphin’s whistle and a human voice, with harmonics that made my teeth ache.

It was coming from the largest tidal pool, about fifty yards from the house. The flashlight caught something in the water. At first, I thought it was a seal tangled in fishing line. Then I got closer.

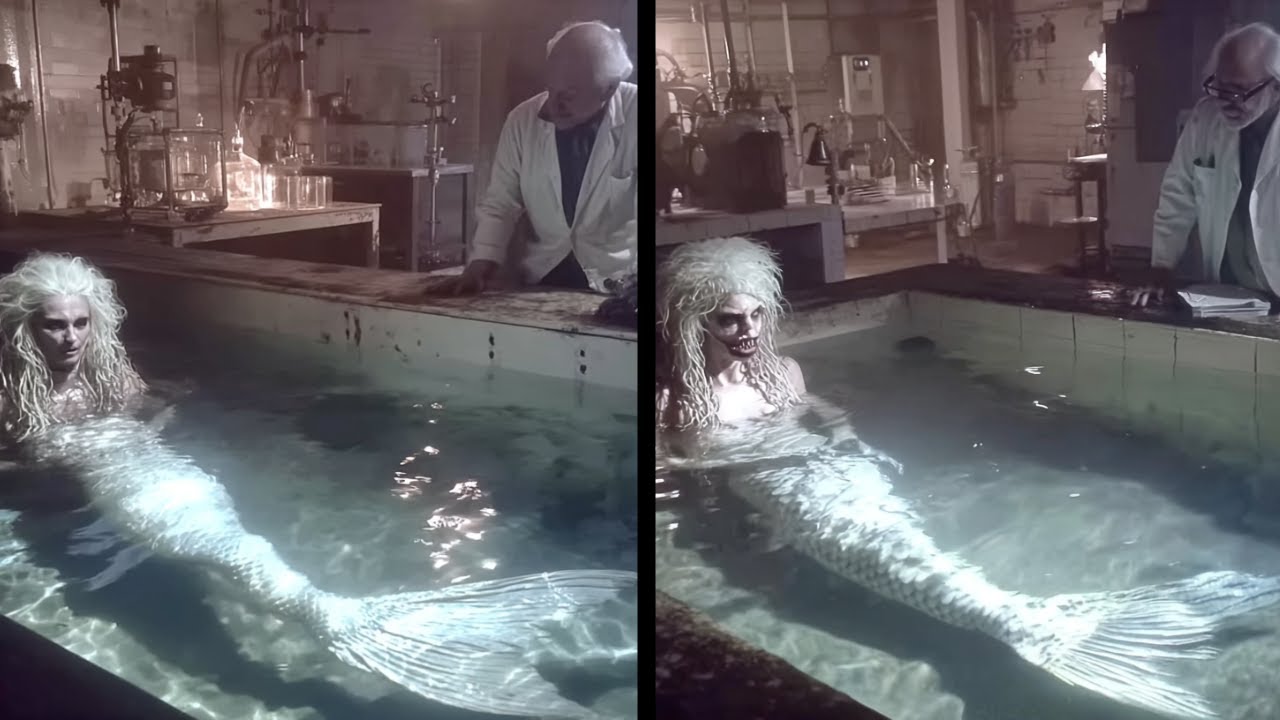

The Impossible Encounter

She was trapped in a massive commercial fishing net, the kind used for dragging. The net was wound around her upper body and caught on the rocks. She was trying to pull herself toward deeper water, but the tide was going out and she didn’t have the strength. I saw the tail first—a horizontal fluke, scaled in dark blue-green, bleeding from several deep cuts. Then I saw the rest. From the waist down, she was fish; from the waist up, human. Not human-like. Human.

She had a young woman’s torso, arms, face, dark hair matted with blood and seawater, hands with webbed fingers and opposable thumbs, and gills—three parallel slits on each side of her rib cage fluttering as she struggled to breathe. Her eyes were large, with nictitating membranes, dark brown and aware.

She was dying. The propeller wounds were deep, her breathing ragged. I had maybe ten minutes before the storm surge hit. If I left her, she’d drown or bleed out. I pulled my diving knife and started cutting the net. She didn’t fight me. She watched as I worked, sawing through the synthetic line. My hands shook from cold and disbelief. When I finally cut the last piece, she tried to move toward the water, collapsed, and lay gasping.

With the wind picking up, I made a decision that defined the next forty years. I got my arms under her shoulders and dragged her toward the house. She was heavy, slippery with blood and seawater, making soft sounds I couldn’t interpret. The basement entrance was open for ventilation; I hauled her down the concrete steps, across the floor, and into the pool.

She sank immediately, then surfaced, gripping the concrete lip, breathing hard through her mouth and gills. I was soaked, exhausted, and beginning to comprehend what I’d done. I’d brought a mermaid into my basement. Something that wasn’t supposed to exist.

Shelter and Recovery

The basement lights flickered on and I got my first clear look at her. She was young, maybe late teens or early twenties. Her face was human but subtly off—the eyes too large, the nose too small, the mouth too wide. Her skin was pale gray-blue, scales starting below her navel and transitioning from skin to scale over several inches. The propeller wounds were bad, still bleeding.

I ran upstairs for my first aid kit and towels. I cleaned her wounds with saline, applied antibiotic ointment, and bandaged them with waterproof gauze. She made soft clicking sounds but stayed still. Her gills were inflamed; I used more antibiotic ointment, careful not to hurt her. When I finished, she swam to the center of the pool, dove under, surfaced, and watched me.

I sat on the concrete floor, wrapped in a blanket, listening to the storm rage outside. Inside, I was in a basement with a mermaid. I didn’t sleep that night. She spent most of it at the bottom of the pool, surfacing to breathe every ten or fifteen minutes. By dawn, the hurricane had passed. The house was intact, but none of that mattered. What mattered was the creature in my pool.

The Choice

I needed to make decisions: treatment, food, secrecy. If anyone found out, she’d end up in a government facility within hours. I made coffee on my camp stove and thought about calling the university, NOAA, maybe the Coast Guard. But I’d seen enough to know what would happen—she’d become a specimen, a research subject, or worse.

I chose to keep her hidden, at least until I understood what she needed. I drove into town for supplies, claiming I’d found an injured seal. The vet gave me antibiotics and wound care supplies; the fish market provided mackerel, herring, and squid. When I returned, she was at the surface, watching me.

I sat at the edge of the pool and spoke slowly. “I’m Robert. I’m going to help you, but you need to stay here. Stay hidden. Do you understand?” She nodded. My hands shook. She understood English.

“Can you speak?” I asked. She tried, but her vocal anatomy wasn’t built for human language. Clicking, whistling, frustration on her face. “It’s okay,” I said. “We’ll figure something else out.”

I changed her bandages, gave her antibiotics mixed with fish, and watched her eat—bones and all. Over the next week, she healed faster than I expected. The propeller cuts closed with new scar tissue, scales growing back lighter than before. We started communicating with a waterproof slate and marker. She drew pictures: fish, other figures with tails, ships with nets. Her family? She nodded. The ship separated you? Another nod. Then more ships, some with sonar equipment, lights, hunting her pod.

“Are there more of you?” I asked. She drew a question mark, then waves, pointing up. She didn’t know where they were. For the first time, I saw grief. She was alone.

The Refuge

I made a decision: I couldn’t release her. Not yet. Even if her wounds healed, I didn’t know if her pod was still in the area, or if she could survive. If she ended up caught again, I wouldn’t be there to help. She would stay in the pool. I told myself it was temporary—a few months, maybe a year. That was forty years ago.

By October 1984, Marina—I’d started calling her that—was fully healed. She was eating regularly, swimming with strength, showing no signs of illness. I should have released her. The rational part of me knew this. But I didn’t. I told myself I needed to monitor her longer, wait for better weather. The truth was simpler: I was afraid for her.

I researched marine mammal hunting, commercial fishing, and naval operations. What I found made releasing her seem like a death sentence. There were reports of unusual catches classified by federal authorities, sonar contacts investigated by Navy vessels, folklore about fishing boats catching something and being ordered to turn it over. The government had been looking for her kind for decades.

I couldn’t release her into that. So, I kept her in the pool, and told myself it was protection.

Communication and Connection

We developed a more sophisticated communication system. Waterproof slates were useful, but limited. I made laminated cards with symbols: fish species, weather, time, emotions, family, danger, ship, net. Marina learned the system faster than I could create it. She could string together complex ideas, clarify meaning with drawings.

She was intelligent, with abstract understanding and a strange sense of humor. She was curious about everything—pool filtration, concrete structure, lights. Artificial light fascinated her. She played with a flashlight, experimented with angles, studied how light bent at the water’s surface.

I brought down books with pictures, marine biology texts, oceanography references, children’s books for vocabulary. She absorbed everything, learned to read. By December, she was reading simple sentences. We had written conversations on a chalkboard. Her letters were crude but readable, her webbed fingers struggling with the pencil.

I asked about her life before the ships. She wrote: “Deep water, cold, we traveled, followed fish.” How many in your family? “12. mother, sisters, others.” Do you think they survived? She wrote, “No.”

I asked what she wanted. Did she want to try to find survivors? Did she want me to release her? She wrote, “Afraid. Ships still there.” “I’ll keep you safe,” I said. “You can stay here as long as you need.” She wrote one more word: “Prison?”

The question hit me hard. Was this a prison? I told myself it was protection, but what was the difference? “No,” I said. “Not a prison. A refuge. You’re free to leave whenever you want.” She wrote, “Safe, but alone.” I had no answer.

Adapting to Captivity

I tried to make the pool less isolating—better lighting, a radio for music and news, enrichment objects, puzzles. I spent hours in the basement every day, not just feeding her, but talking, teaching, learning. She taught me things about the ocean I’d never known—maps of underwater currents, feeding grounds, migration patterns. She corrected scientific literature, explained dolphin communication nuances.

I started keeping detailed notes, documenting her health and needs, but also conducting research. The difference, I told myself, was that she was a willing participant. She wanted to teach me, wanted me to understand her world. I never hurt her, never took samples without asking, never pushed her beyond comfort.

But I was still keeping her in a basement pool. As winter turned to spring and spring to summer, temporary became permanent. My life shrank to the house, the pool, and Marina. I avoided relationships, stopped attending conferences, isolated myself from anyone who might ask too many questions.

Marina never complained. She seemed content. She never demanded release, never showed signs of depression. She created a life in the pool, limited as it was. I told myself this proved I’d made the right choice. She was safe, healthy, intellectually stimulated. But sometimes I’d find her floating at the surface, motionless, and wonder if she was sleeping or just waiting.

The Years Pass

By 1986, keeping Marina hidden was the central fact of my existence. Every decision, every relationship, every routine was built around the secret. I developed elaborate systems—backup pumps, generators, soundproofing, white noise generators to mask her vocalizations. I told neighbors I was running aquaculture experiments for the university.

My work changed. I focused on projects I could do from home: acoustic analysis, data processing, grant writing. Colleagues noticed. Dr. Sarah Chen asked if I was okay. I told her I was dealing with family issues.

The isolation was difficult. I couldn’t have friends over, couldn’t date. Anyone close enough to visit would eventually hear something, notice something, ask questions. I had one close call in 1987—a visiting marine biologist who wanted to see my setup. She left disappointed when I refused her overnight stay.

Fish deliveries became routine—rotating suppliers, never buying more than fifteen pounds at a time, keeping detailed records of her diet and health. She grew, matured, read voraciously, discussed books, questioned human culture. She asked about families, cities, war. I had no good answers.

She was particularly interested in marine biology, correcting my research, explaining dolphin communication. I incorporated her insights into my work, published papers, won grants. The irony wasn’t lost on me—my career improved because I was keeping a sentient being in my basement.

By 1990, Marina was my closest companion. We spent hours together—meals on the pool deck, reading aloud, watching television. She loved nature documentaries, soap operas, sitcoms, asked me to explain cultural references. She adapted to captivity remarkably well. Too well.

The Guilt

She seemed happy, content, never demanded release. But sometimes I’d wake at 3 a.m. and find her floating, motionless, waiting for something I couldn’t give her. The guilt grew worse as years passed. By 1995, she’d been in the pool for eleven years—since she’d felt ocean currents, seen natural light, tasted wild fish. Eleven years in a concrete cylinder.

I tried to rationalize it—she was alive, likely dead if I’d released her. The ships were still out there, reports of unusual catches, sonar contacts, federal interventions. Was survival enough? Was mere existence enough? I never asked her directly. I was afraid she’d say no.

Instead, I kept improving the pool—underwater speakers, more lights, day-night cycles, a laptop with modified keys. She learned to type, kept a journal. Sometimes she showed me entries, things she wanted me to understand.

One entry from 1996 stayed with me:

Robert asks if I am happy. I do not know this word’s meaning anymore. I am not in pain. I am not afraid. I have food and learning and someone who talks to me. But I remember the deep water. I remember swimming for days and feeling current change. I remember the taste of fish I caught myself. I remember mother’s songs. Are these things happy or is this safe? I do not know.

I kept that entry in my desk drawer, a reminder of the choice I couldn’t make. Marina stayed in the pool. I stayed in the house. The years kept passing.

Epilogue: The Choice

People ask why I’m coming forward now. The Navy found Marina three months ago, and what happened after makes silence pointless. More than that, I need someone to understand the choice I made in 1984—whether it was protection or imprisonment.

For forty years, I told myself I was saving a life. Now, I’m not sure. The truth about what lives in our oceans is far stranger than anything you’ve imagined. I kept Marina hidden, studied her, learned from her, and built a life around the secret. But I never answered her question: Was this a prison?

I hope this account helps someone else understand that the line between protection and captivity is thin, and the cost of crossing it is measured in years, in guilt, and in the silence of deep water.