Mountain Ranger Saved 2 Small Bigfoot and Found the Truth About Their Species

I never believed in Bigfoot.

Not in the way tourists mean it—wide-eyed and hopeful, wanting the woods to be magical. And not in the way the internet means it, either, with grainy videos and people selling certainty like bait.

I believed in weather patterns. Trail erosion. Bear behavior. The predictable ways people got themselves killed when they stopped respecting distance and elevation and daylight.

I believed the wilderness didn’t care about your feelings.

That belief held for twenty years in the Cascades.

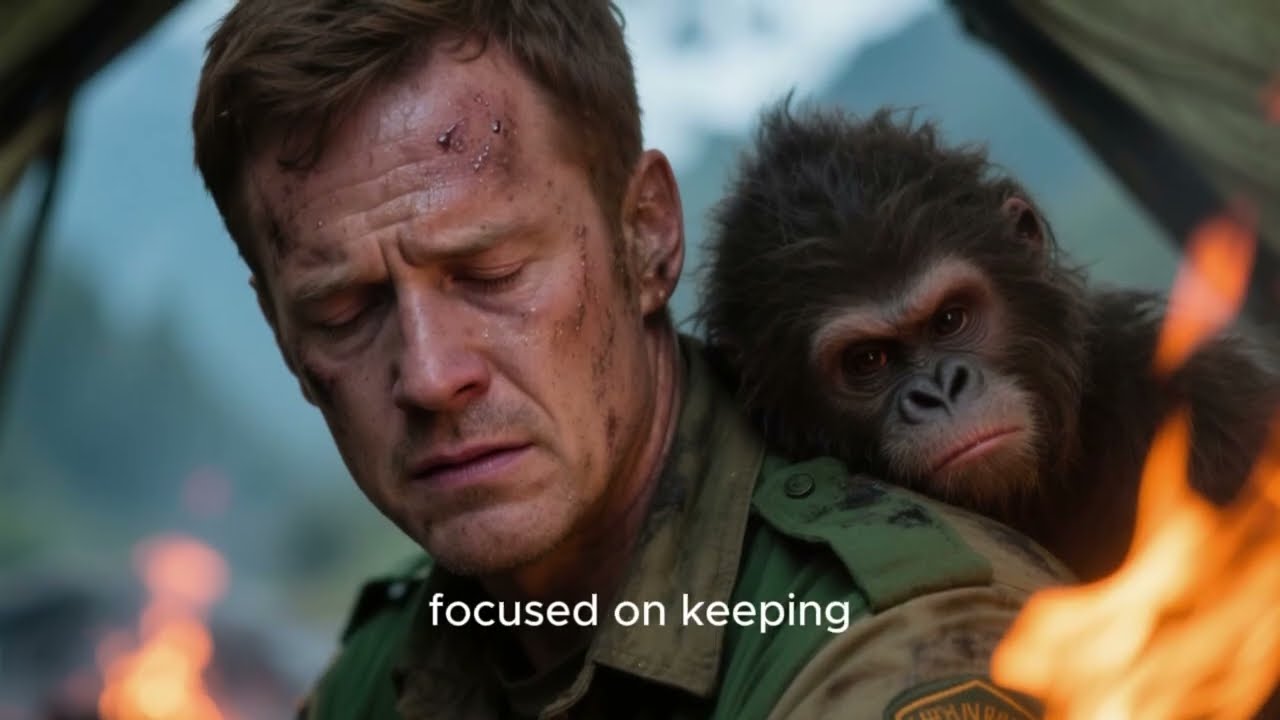

Then a fire pinned me against a cliff with two small, furred children who looked at me like they understood exactly what death was—and like they also understood I might be the last person between them and it.

I still hear their screams in my sleep.

Not because they were loud—though they were—but because they were intelligent. There’s a difference. A deer will cry and run. A cougar will shriek and vanish. But those sounds weren’t instinctive noise.

They were language stripped down to its rawest form:

Help.

And when you’ve worked the backcountry long enough, you learn that the woods don’t produce many true “firsts.” Everything is usually a variation on what you already know.

That day was the exception.

I’ve been a mountain ranger for two decades in the Cascade Range, mostly in the remote sections where tourists rarely venture. My job is trail maintenance, wildlife monitoring, search and rescue. Most days I’m alone, which is exactly how I like it. The mountains have always made more sense to me than people.

I grew up here—the son of a logger who taught me to read forest sign the way other kids learned to read books. I could identify tracks before I could tie my shoes. I knew the difference between “fresh” and “fresh enough to get you killed.” My father said the woods would take care of you if you respected them.

He died in a logging accident when I was fifteen.

The mountains still felt like home after that. Maybe more so. I became a ranger because I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. I tried college for one semester—forestry management—and couldn’t stand the fluorescent lights. I needed the smell of wet bark and the sound of a creek under ice. By twenty-three, I had my certification and started taking the backcountry beats everyone else avoided. Too remote. Too lonely. Too dangerous.

Perfect.

Over those years I heard the Bigfoot stories. Every ranger does. Hikers came back swearing they’d heard strange howls or found footprints that didn’t belong to any known animal. Old-timers at the station talked about glimpsing something tall and hairy disappearing into the treeline.

I smiled. I nodded. I filed it under campfire noise.

Sure, I’d seen odd tracks—big prints that could’ve been from bears walking on hind legs, or distortions from melting snow. I’d heard screams in the night that sounded inhuman until you realized a mountain lion can make a noise that will convince your brain a woman is dying in the trees.

Nothing I’d seen ever convinced me.

Looking back, I realize how arrogant that was.

The wilderness is vast. The wilderness is older than our categories. The wilderness holds secrets that don’t care whether you believe in them.

And some secrets don’t reveal themselves until the exact right moment—when you’re alone, under pressure, and there’s no room left for denial.

That summer was the driest on record. The kind of dry that makes everything brittle, even your thoughts. Streams that usually ran full were reduced to trickles by June and dust by July. Understory that stayed damp even in August crumbled into kindling. Every step sent up little puffs of powder. Twigs snapped under my boots like gunshots.

The forest felt fragile—like it was holding its breath and waiting for disaster.

We staged equipment early: water trucks, bulldozers, helicopters. Daily briefings. Trail closures. Evacuations. The tension in the ranger station was physical. Nobody said it outright, but we all knew it wasn’t a question of if the big fires would come. It was when, and how many of us would get caught between wind shifts.

I had a bad feeling I couldn’t name. I checked my emergency gear obsessively—fire shelter, extra batteries, water purification tablets, first aid supplies. The guys teased me for it. I let them. I’d rather be mocked than dead.

On the morning of August 23rd, I headed out before dawn to check a series of remote campsites along the upper ridge. The air was thick and still, with that metallic taste that comes before lightning storms. I packed extra water and fire gear because I’ve learned the hard way what drought plus lightning means: strikes without rain.

Around noon, I saw the first wisps of smoke rising from a canyon three miles northeast of my position.

Within minutes my radio crackled with reports: multiple strikes, growing fires, wind erratic. Dispatch called for all available personnel to report to staging areas. I was too far out to make it back quickly. I radioed my location and started hiking toward the nearest evacuation route.

The wind picked up as I descended into a narrow valley, and suddenly the smoke wasn’t distant anymore.

It was everywhere.

Thick, choking, turning the sun into an angry orange coin. I pulled my bandana over my nose and mouth and picked up my pace. The fire was moving faster than expected, pushed by winds that couldn’t decide which direction they wanted to kill you from.

That was when I heard the screaming.

Not human screaming.

But close enough that my blood ran cold.

High-pitched. Desperate. Coming from off the trail to my right, deeper into brush so dry it sounded like paper when it moved.

Training tells you to keep moving toward safety. Training tells you not to get pulled off route by mystery sounds when the air itself is becoming a weapon.

But something about those cries made me stop.

They sounded young.

Terrified.

Helpless in a way that was… deliberate.

I turned off the trail and pushed through underbrush, fighting brambles and deadfall. Smoke thickened. I could hear the fire now—a distant roar that was growing louder by the minute, like a freight train in the trees.

Every instinct screamed at me to turn back.

The cries kept pulling me forward.

I found them in a small clearing at the base of a cliff, trapped between rock face and an advancing wall of flame moving through dry brush like it had purpose.

Two small figures huddled against stone.

Four feet tall, maybe a little more.

Covered in reddish-brown fur.

For a moment my brain refused to process what I was seeing. It tried to find a familiar label—bear cubs, maybe, though bear cubs don’t stand like that. Young elk, though elk don’t have hands.

These had hands.

Disturbingly human hands, furred and broad, fingers splayed against the rock as if trying to climb through it.

They looked like a cross between apes and human children, but not in the cartoonish way people imagine. In a way that made your mind recoil because it was too close to you.

My first thought—honest thought—was that I was hallucinating from smoke inhalation.

That had to be it.

I blinked hard, expecting the vision to clear and become something explainable.

It didn’t.

They stayed.

Unmistakably real.

Unmistakably terrified.

The larger one—maybe four and a half feet—positioned itself in front of the smaller, using its body as a shield. The stance wasn’t just instinctive. It was a decision. A choice made with awareness.

Sacrifice.

Love.

The smaller one was hurt.

Even from twenty feet away I could see its left leg was damaged, fur dark and matted with blood. It leaned heavily on the larger one, unable to put weight on the injured limb. Its breathing was fast and shallow. Its eyes rolled back and snapped forward again.

Shock.

The larger one made those terrible screams again when it saw me, pressing itself harder against the cliff. It bared its teeth and swung its arm out like a barrier.

It wasn’t trying to attack me.

It was trying to protect the other.

The fire was maybe two hundred yards away and closing fast. Embers floated through the smoke like deadly fireflies. We had minutes before this clearing became an oven.

I dropped my pack and pulled out my emergency fire shelter—a reflective tent designed to protect people from burnovers. It was rated for one adult, maybe two children.

It was all I had.

I shook it out and staked the corners as fast as my shaking hands would allow. The larger creature watched me with wary eyes that tracked every movement like it was reading intent, not just motion.

I pointed at the shelter.

Then at them.

Then at the flames.

The larger one seemed to understand.

But it didn’t move.

The smaller one whined weakly, and I saw fresh blood seep through fur. That was when the simplest truth slammed into me:

They hadn’t run because they couldn’t.

The injured one couldn’t walk.

And the other wouldn’t leave it behind.

My chest tightened with something I didn’t have time to name.

Respect, maybe.

Or the kind of awe you feel when you watch something do the right thing at the cost of its own survival.

The fire surged closer. Heat pressed against my face like an opening oven. There wasn’t time for trust to develop gently.

I ran toward them.

The larger one shrieked and swung at me with surprising strength. Its fist clipped my shoulder and sent me stumbling sideways. Pain flashed hot down my arm.

I kept moving.

I grabbed the injured one under its arms. It was lighter than I expected—maybe sixty pounds—and it made a heartbreaking sound as I lifted it. Not a scream. A broken, breathless cry that sounded like it understood exactly what was happening and was too weak to protest.

I carried it toward the shelter.

The larger one followed, still vocalizing, still torn between attacking me and staying with its companion. I shoved the injured one into the shelter and pointed again—sharp this time, urgent.

The larger one hesitated for half a heartbeat.

Then it scrambled inside and immediately pressed against the injured one, making soft cooing sounds meant to comfort.

I squeezed in after them and pulled the shelter closed just as the fire hit.

The world became heat and roar.

The reflective fabric glowed faintly in the orange light. The air inside tasted like smoke and metal. The temperature climbed so fast it felt like being cooked.

The two young creatures huddled together in the center, eyes huge, bodies shaking. I pulled them toward me and wrapped my arms around both, pressing their faces against my chest to help them breathe the thinnest pocket of air.

The larger one struggled at first. Its muscles were tight, its hands pushing, its fear turning into frantic energy.

I held firm and murmured nonsense—soft sounds, the same tone I’d used to calm a terrified dog, the same steady rhythm I’d used on lost kids.

Eventually it stopped fighting.

It pressed against me, trembling.

The injured one went limp, barely conscious. I could feel its heartbeat—rapid, irregular—against my ribs.

The roaring outside was deafening. Burning debris hit the shelter with dull thumps. The ground vibrated. At one point a massive branch—or maybe a whole tree—crashed nearby and sent a shockwave through the earth.

The creatures screamed and tried to bolt.

I used every ounce of strength to hold them down.

“Stay,” I said over and over, though they didn’t know the word. “Stay. Stay with me.”

The heat reached a point where I thought the shelter was failing. Sweat poured off me. My tongue felt thick. My throat burned. The creatures panted like dogs, tongues lolling, and I wondered if they’d collapse from heat stroke before the fire even passed.

Training says: keep low, protect your airway, wait it out.

Training also feels like a joke when you can feel an inferno trying to turn you into a story no one will believe.

Then the smaller one stopped breathing.

My heart nearly stopped with it.

I shifted it, tilted its head back, and used my thumb to clear its mouth of soot and saliva. I didn’t know if CPR worked on something that shouldn’t exist, but instinct doesn’t ask permission.

I gave it two quick breaths.

The creature coughed weakly.

A shallow inhale.

Then another.

The larger one made a sound that I swear—swear—contained gratitude mixed with grief.

And then, slowly, the roar outside began to diminish.

From freight train to crackle.

From crackle to hiss.

The temperature stopped climbing.

The worst of the fire moved on to consume something else.

We might actually survive.

When the sound faded enough to hear my own ragged breathing, I risked opening the shelter.

The world outside looked like another planet. Black ground, gray ash, smoke curling from everything. Glowing embers scattered like eyes across the scorched earth. The air was acrid and shimmering with heat, but it was air.

The two young creatures were unconscious now—heat exhaustion, shock, smoke.

I checked pulses.

Fast, but steady.

They needed water. Medical attention. Fast.

I got my radio working and called for evac, giving coordinates with a voice that felt far away.

Dispatch asked what kind of casualties I had.

I stared at the two small furred bodies at my feet and felt my brain try to protect itself again.

“Two juveniles,” I said carefully. “Heat exposure. Smoke inhalation. One with a leg injury.”

Dispatch didn’t ask for species. She confirmed a helicopter within the hour.

While we waited, I cleaned the wound on the injured leg. It looked like it had been caught in an old trap—metal teeth had done what metal teeth do. I wrapped it in gauze and elevated it as best I could.

The larger one stirred when I offered water.

Its eyes opened slowly.

And they weren’t animal eyes.

Not the blank panic of a deer or the predatory focus of a bear.

These eyes studied me.

It made a low sound—questioning.

I held the water bottle to its lips. It hesitated, then drank. Drained half the bottle. Then it looked at the unconscious one and made an urgent grunting sound.

I understood.

I helped lift the injured one’s head and dribbled water into its mouth.

The smaller one coughed, swallowed.

The larger one’s shoulders lowered slightly, tension easing like a knot loosening.

Then it reached out and touched my hand.

Fingers startlingly like human ones if you ignored the fur and the proportion. It squeezed gently—just pressure, not force.

A soft sound escaped it, almost like a sigh.

In the smoking ruins of a forest, we sat there like three survivors of the same impossible event.

When the helicopter approached, the larger one tensed hard.

Its head snapped up. It tried to stand, panic returning. The noise and vibration triggered something deep.

But it wouldn’t leave the injured one.

I put my hand on its shoulder and pressed gently, grounding it with touch the way you do with animals—yes, animals—and with people.

“It’s okay,” I said, even though the words were thin. “It’s okay.”

It looked at me, looked at its companion, and slowly sat back down.

The helicopter crew came through smoke and stopped dead when they saw what I had.

The medic—young, fresh-faced—froze mid-step, mouth open. The pilot’s voice crackled over the radio with confused questions that turned into clipped silence.

I waved them in.

The medic knelt beside the injured one and started checking vitals with hands that moved on training even while his face showed disbelief. When the larger one growled, I stepped between them and shook my head.

The larger one backed off, but watched with obvious suspicion—eyes tracking every motion, reading intent.

Getting them into the helicopter was the hard part.

The larger one refused to board until I climbed in first.

Even then it crouched in the corner with the injured one held against its chest like a child, making low nervous sounds. I sat beside them with one hand on its arm the whole flight, feeling it tremble with fear.

The pilot kept glancing back like he expected the creatures to vanish if he stopped looking.

Dispatch ordered radio silence. Someone high up had made a decision about how this would be handled.

When we landed at the ranger station, three black SUVs were waiting.

And a group of people in suits who did not belong to the Forest Service.

My supervisor stood with them, face tight, avoiding my eyes.

A woman with steel-gray hair stepped forward like she owned the air. She introduced herself as “federal,” though she didn’t give a name I could use. Her gaze slid over the creatures with something that looked like familiarity.

That chilled me more than the fire.

She directed the medics to take the injured one to a building I’d never been allowed to enter.

Then she turned to me. “What you experienced is now classified.”

I stared at her. “You can’t be serious.”

“I’m serious,” she said, and her tone didn’t allow argument. “You will be debriefed. You will sign documents. You will not speak about this.”

When I started to protest, she held up a hand and said something that shut my mouth:

“You just saved two members of the rarest and most protected species on this continent. Your cooperation is necessary to ensure their survival.”

Protected.

Species.

The words didn’t fit together in my head.

The larger juvenile wouldn’t leave the injured one, so they let it stay. They led us into the secure building and into a space that looked like a veterinary clinic built for giants—oversized doors, reinforced walls, equipment I didn’t recognize.

A veterinarian came in—calm, practiced, not shocked. That was another knife of reality.

She examined the wound quickly, stitched with efficient hands, administered fluids and antibiotics. She spoke softly the entire time, and the larger juvenile seemed to understand enough—tensing when she warned something might sting, relaxing when she said “almost done.”

It watched her, then glanced at me, checking my reaction before deciding how afraid to be.

Like I was an anchor.

After the vet finished, the gray-haired woman took me to a conference room.

She spread photographs across the table.

Dozens.

Bigfoot in the wild—family groups, tool use, shelters woven from branches, stone circles in moss. Video stills of them communicating through gestures and sounds. Maps of protected habitat corridors, population estimates, migration routes.

The images weren’t grainy hoaxes.

They were clean. Close. Clinical.

Real.

The woman watched my face change and spoke as if she’d given this lecture before.

“The government has known for decades,” she said. “They’re not just animals. They’re not human. They’re a relict hominid population that survived in remote wilderness through intelligence, elusiveness, and protection.”

“Protection by who?” I asked, though I already knew the answer.

She didn’t smile. “By agencies like mine.”

She told me secrecy wasn’t about cover-up. It was about survival. Because the moment Bigfoot became public truth, the mountains would fill with hunters and thrill-seekers and profiteers. They’d be hunted, captured, trafficked, turned into trophies or experiments.

“We’ve run the scenarios,” she said. “Every one ends the same way.”

She told me the two juveniles I’d rescued were from a small family group in the high country. The fire had separated them from their parents and scattered—or killed—the rest. The leg injury came from an illegal trap set years ago and forgotten.

Without me, she said, both would have died.

The agency was trying to locate surviving adults and reunite the juveniles with them.

In the meantime, they’d be kept at a secure facility.

Then she asked me a question that sounded simple and landed like a weight:

“Will you visit them during recovery?”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because you’re the only human they’ve shown consistent trust toward,” she said. “And right now, trust is a medical resource.”

I agreed without hesitation.

The facility was hidden deep in the forest, accessible only by unmarked roads. Inside, it was half clinic, half research center—observation rooms, recovery wards, long-term habitats that mimicked natural clearings with living trees rooted in soil beds and a stream running through one corner.

Not a makeshift response.

A permanent operation.

That realization stayed with me: this had been happening for years. Maybe decades. The world I thought I knew had always had an extra layer.

The habitat where they placed the two juveniles was designed like a forest room—logs for climbing, rocks for tool use, puzzle feeders that required problem-solving. The walls were painted with scenes so realistic my eyes kept trying to interpret them as windows.

The staff called the larger juvenile Guardian.

The injured one, quieter and more observant, they called Scout.

Watching them was like watching intelligence move through a body built for wilderness.

They didn’t just occupy space. They modified it—arranging logs and stones in deliberate patterns. Guardian built small structures from branches: some like shelters, others like… art. Scout watched and occasionally contributed, even with the injured leg limiting mobility.

The staff told me it was typical. Bigfoot manipulated their environment constantly. Shelter, communication markers, territorial boundaries—possibly even spiritual or aesthetic functions humans didn’t fully understand.

During my visits, I learned their moods the way you learn weather.

Guardian had vocalizations for different situations: a soft coo when content, a sharp bark when alert, a low rumble when annoyed. Scout was quieter, using precise head tilts and small hand gestures the staff said were common in regional groups.

Communication, no doubt about it.

Language without words.

The bond between Guardian and Scout was the hardest part to watch, because it was so familiar. Guardian never left Scout’s side. It groomed Scout’s fur, brought food, positioned itself between Scout and anything unfamiliar.

One day Guardian tried to share food with me—offering a piece of fruit with an earnest expression that made me laugh and then, unexpectedly, nearly cry.

Because it wasn’t trained behavior.

It was social behavior.

It was culture.

Three weeks after the fire, the agency located two adults near the burned area—trail cameras and heat sensors catching a large female and a smaller male showing search behavior. DNA from hair samples matched Guardian and Scout.

Their parents were still looking.

The reunion was planned at dawn in a lightly burned clearing near where I’d found the juveniles.

We flew in by helicopter to a drop point and hiked the rest. Guardian and Scout were nervous during the ride, but perked up as we approached the clearing, like the land itself was speaking to them.

When we arrived, the handlers removed the lead ropes and stepped back into a wide perimeter.

Guardian and Scout stood in the center and turned slowly, taking in the scorched landscape.

For a moment, nothing happened.

Then a shape moved at the edge of the treeline.

A massive female stepped into the clearing.

Seven feet tall, maybe more. Fur darker than the juveniles’. She moved with a grace that didn’t make sense for that mass. She stopped when she saw them, head tilting in the same gesture I’d seen Guardian use a hundred times.

Guardian screamed.

Not fear.

Joy.

Recognition so intense it sounded like pain.

Guardian ran to her.

Scout followed, limping but determined.

The female dropped to her knees and gathered both into her arms, making a sound that was part sob, part purr. She ran her hands over them, checking injuries, smelling fur, pressing her face to their heads like she was trying to inhale proof they were real.

A second adult emerged from the trees—a male, slightly smaller but still imposing. He approached cautiously, eyes fixed on the humans at the clearing’s edge. He made a low warning sound and positioned himself between his family and us.

The female responded with softer vocalizations that, if you were foolish enough to translate them, sounded like:

It’s okay. They helped.

That was when Guardian pulled away.

And ran toward me.

Every handler tensed. Someone’s hand went toward a tranquilizer rifle.

Guardian stopped in front of me and reached out.

Touched my hand.

Those dark eyes held mine, and I knew what I was seeing.

Goodbye.

Thank you.

Something that needed no translation.

I squeezed Guardian’s hand gently—one last pressure—and then I let go, nodding toward the family.

Guardian looked back at its parents, then at me, then back again.

Then it turned and walked back into the female’s embrace.

Scout made a smaller gesture, a wave that was eerily human, then leaned into the female’s arm.

The family group turned and melted into the forest.

Before they disappeared completely, the adult female paused.

She approached within thirty feet—closer than I expected—and looked directly at me. Her gaze was intense and evaluating, like I was being judged in a way that had nothing to do with science.

Then she placed one massive hand over her chest and tilted her head.

Gratitude.

I mirrored the gesture—hand over heart, head bowed slightly.

Something passed between us then: recognition, respect, the understanding that we were both creatures who would burn for our young.

Then she turned and followed her family into the trees, and the forest swallowed them like it had always known how.

I signed the papers. I agreed to keep quiet.

They offered me a choice: return to my ranger duties and pretend none of it had happened, or join the agency and work on Bigfoot conservation full-time.

I stayed with the Forest Service.

But I accepted a consulting role.

Now, on top of my regular patrols, I report signs—twisted saplings, odd stick structures, stone arrangements that appear after rain. I know where they travel and where they shelter, and I protect those places as best I can.

Sometimes I hear sounds in the forest that I know aren’t bear or elk.

Sometimes, at dawn, I see a shape moving through the trees on two legs with a grace no human can match.

Once I found a spiral of smooth river stones arranged on a trail I’d walked a hundred times—too precise to be accident. I sat with it for a long time, trying to understand whether it was a greeting or a warning.

I took a photo. Then I reconstructed the spiral exactly as I found it.

If it was a message, I wanted the sender to know I’d received it.

People still tell Bigfoot stories around campfires.

I still sit there and say nothing.

And the hardest part—the part that keeps me awake some nights—is not the secrecy itself.

It’s the question I can’t stop asking:

When I found two juveniles trapped by fire, where were the adults?

Because I’ve seen the agency maps now. I’ve seen the footage. I know how intelligent they are, how fast they move, how fiercely they protect their young.

So why were Guardian and Scout alone?

The official answer is simple: fire scatters families, panic breaks patterns, chaos kills.

But I remember the way the adult male watched the treeline that morning, not just wary of us—wary of something deeper in the woods.

And I remember something else, too.

That day in the shelter, when the world was nothing but roar, heat, and smoke… there was a moment—brief, impossible—when the larger juvenile stopped screaming and went perfectly still.

As if listening.

As if hearing something beyond the fire.

A low vibration I felt more than heard, like thunder under the ground.

At the time I told myself it was the fire. The earth cracking. My own fear turning sensation into meaning.

Now I’m not so sure.

Because last month, on a patrol route I’ve walked for years, I found another stone arrangement—this time not a spiral.

A line.

A boundary.

And pressed into the mud beside it was a track that wasn’t Guardian’s or Scout’s.

Too big.

Too deep.

And angled in a way that suggested whoever made it had been standing still for a long time.

Watching.

Waiting.

The mountains are full of secrets.

I used to think Bigfoot was one of them.

Now I know the real secret is worse—and stranger:

Bigfoot aren’t just hiding from us.

Sometimes they’re hiding from something else, too.

And if the fire that day wasn’t an accident…

Then I didn’t just rescue two young Bigfoots from the wilderness.

I may have pulled them out of the first move in a game I didn’t know existed.