Secret Guardian of Young Bigfoot: When the Feds Discovered His Hidden Charge, a Legendary Sasquatch Folklore Tale Unfolded

In the high, wet heart of the Cascade Foothills, where the Douglas firs grow so thick they blot out the stars and the rain falls like a curtain of iron, they tell the story of Anthony Collins.

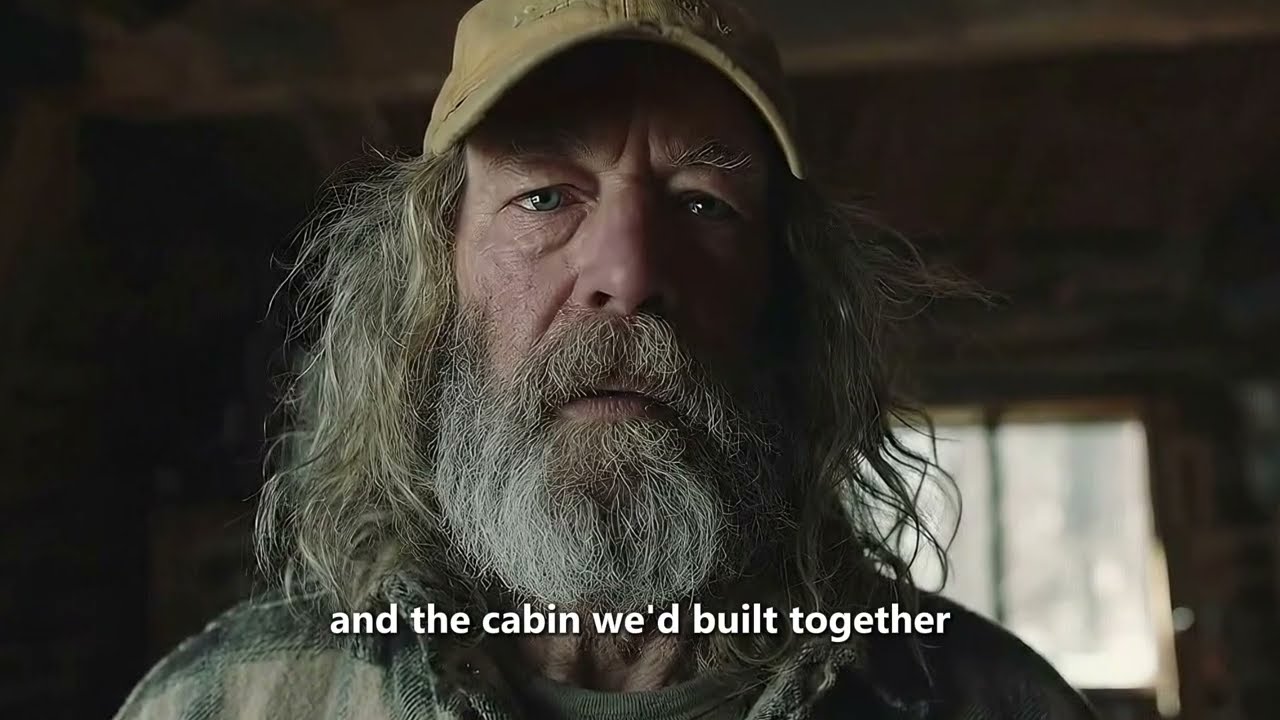

To the people of Oakridge, Anthony was a ghost in a flannel shirt. He was a widower, a retired mechanic with grease permanently etched into his fingerprints, and a man who bought his solitude acre by acre. He lived forty minutes down a logging road that turned to soup in the spring and ice in the winter. He came to town only for coffee, flour, and books.

But the mountain knew better. The mountain knew that Anthony Collins was never truly alone.

The story begins on a night in March of 1972, the night the sky tried to wash the world away. It was the birthday of Anthony’s late wife, Margaret, and the storm was a howling thing, tearing trees from their roots. Anthony, sitting by his lamp, heard a sound that cut through the thunder. It wasn’t the roar of a bear or the scream of a cougar. It was the high, desperate wail of a child.

He went out into the deluge. Down by the swollen creek, where the hillside had collapsed into a slurry of mud and stone, he found him.

He was trapped in the debris—a small, shivering thing, no bigger than a toddler, covered in reddish-brown fur matted with clay. He had a gash on his shoulder and eyes that held a terrifying intelligence. He was a child of the wood, a Sasquatch, the creature the tribes whispered about and the white men laughed at.

Anthony did not laugh. He saw a life in the mud. He pried the branches apart, lifted the creature—who weighed no more than forty pounds—and carried him into the warmth of the cabin.

He named him Moss, for he belonged to the green, quiet places of the earth.

For twenty years, the cabin became a fortress of secrets.

Moss did not stay small. He grew like a sapling reaching for the sun. By the time the snow melted that first spring, he was walking. By autumn, he was helping Anthony in the workshop, handing him wrenches with hands that were large but possessed a delicate, shocking grace.

Anthony built a shed, then expanded it, then expanded it again. He taught Moss the rules of the invisible: Never cross the road. Never show yourself to the metal beasts that roar. Walk on the rocks to hide your path.

But Anthony did more than hide him. He taught him.

It began by accident, with a finger pointing at a picture of Mount Rainier in a newspaper. Anthony spoke the word: “Mountain.” Moss tried to speak it back, his throat rumbling like stones in a riverbed. He could not form the human sounds, but his mind was a sponge.

Anthony brought home children’s books. Then novels. Then encyclopedias. He watched as the creature—now seven feet tall and weighing four hundred pounds—sat by the woodstove, turning pages with a reverence that shamed most men. Moss learned of the world beyond the trees. He learned of cities, of oceans, of wars, and of peace.

He learned to draw. He took charcoal and paper and captured the soul of the forest—the owl in flight, the twist of the cedar root, the face of the old man who had saved him.

They became a family of two. The old mechanic, whose heart was failing, and the giant of the woods, who brewed the coffee in the morning and lifted the heavy beams when the roof needed repair. They were two castaways on an island of timber, bound by a secret that could destroy them both.

But the world is a jealous thing, and it hates a secret.

In the early nineties, the silence began to break. It started with a young couple, the Hartmans, who bought land nearby. They were hikers, explorers, people who looked at the woods and saw a playground.

Moss, now twenty-two years old and standing seven feet, eight inches, grew careless. Or perhaps, he grew lonely. He went to a spring to drink in the twilight, and the woman saw him.

She saw the giant. She saw the face that was not an ape, but a person. She screamed, and the clock began to tick.

The rumors started in Oakridge. Then came the scientists. Dr. Richard Brennan, a man with a hunger for fame in his eyes, arrived with cameras and plaster kits. He found the tracks. He found the hair. He drew lines on a map that pointed straight to Anthony’s door.

Anthony tried to fight it. He bought more land, spending his life savings to create a buffer of silence. He built a hidden bunker deep in the woods, a hole in the earth to hide his son.

“You must go,” Anthony told Moss, his voice trembling. “Go deep. Go where they cannot find you.”

Moss looked at the old man. He looked at Anthony’s shaking hands, his gray skin. He signed with his massive hands—a language they had invented together.

No. You are here. I stay.

He would not leave the man who had pulled him from the mud.

The end of the quiet years came on an October morning in 1991.

It wasn’t a raid. It was a procession. Sheriff Morrison, a good man caught in a bad spot, led them. Behind him were the federal agents, Pierce and Valdez, wearing suits that looked wrong against the pines. And with them was Dr. Brennan, vibrating with the thrill of the hunt.

Anthony met them on the porch. He stood like an old oak, roots dug deep.

“We know,” Agent Pierce said, not unkindly. “The DNA doesn’t match anything on record. The tracks lead here. Mr. Collins, if there is an endangered species on this land, we have a duty to protect it.”

“Protect it?” Anthony scoffed. “Like you protect the wolf? Like you protect the bear? You mean tag it, collar it, and put it in a cage.”

“We have a warrant,” the agent said softly.

Anthony looked at the Sheriff. He looked at the woods. He knew the game was over. He had played for twenty years, but the house always wins.

“You don’t need a warrant,” Anthony said.

From the edge of the treeline, a shadow detached itself from the dark.

Moss stepped out.

The gasps of the men were loud in the clearing. Dr. Brennan fell to his knees. The agents reached for weapons they did not draw.

Moss walked into the sunlight. He was a mountain of fur and muscle, a creature of nightmares. But he did not roar. He did not charge. He walked with the slow, sad dignity of a king surrendering his sword.

He stopped ten feet from the agents. He looked at Anthony, seeking permission. Anthony nodded, tears cutting trails through the grease on his cheeks.

Moss reached into a leather pouch at his waist. He pulled out a piece of paper. He walked to Agent Pierce, the woman who held the power of the government in her hands, and he offered it to her.

It was a drawing. It showed the forest. It showed the cabin. And at the bottom, written in the block letters of a child learning to write, was a single word:

HOME.

The silence that followed was heavier than the storm of 1972.

“He… he drew this?” Brennan whispered.

“He wrote it,” Anthony said, his voice cracking. “His name is Moss. He reads at a college level. He understands history. He paints. He is not a specimen. He is my son.”

Agent Pierce looked at the drawing. She looked at the giant standing before her, waiting for judgment. She looked at the old man who had defied the world to save a life.

“He is a person,” she whispered.

The battle that followed was not fought with guns, but with words. It was fought in closed rooms in Washington D.C., and in the quiet cabin under the firs.

They brought in bioethicists. They brought in lawyers. They tested Moss, not with needles, but with questions.

Who are you? they asked.

I am Moss, he wrote. I am the one who watches.

What do you want?

I want to stay. I want him not to be alone.

The verdict, when it came, was a secret one. The government realized that to cage Moss would be a crime, not against nature, but against humanity. To reveal him would be to destroy him.

So they made a treaty. The Collins property was designated a federally protected habitat, a sanctuary for a “unique biological entity.” No tourists. No cameras. No interference.

Moss would stay.

Anthony Collins died two years later, in the autumn of 1993. He died in his chair by the woodstove, his heart finally giving out.

He was not alone. Moss was holding his hand.

“You were the best thing,” Anthony whispered to the giant. “Find your people. Be happy.”

When the Sheriff came to collect the body, he found the cabin clean. He found the journals Anthony had kept, chronicling twenty years of miracles.

And he found Moss, standing on the porch, watching the hearse take his father away.

The agents tried to tell Moss he could leave. They told him he could go north, to the deep Yukon, to look for others like him. They offered to help him.

Moss listened. Then he went to his chalkboard, the one Anthony had used to teach him the alphabet.

He wrote: THIS IS HOME. I KEEP THE WATCH.

They say Moss is still there.

The cabin is old now, the wood gray and weathering, but the roof is sound. The path is clear of weeds.

Hikers who stray too close to the boundaries of the Collins Sanctuary sometimes report strange things. They say they feel eyes watching them—not the predatory eyes of a cougar, but the sad, wise eyes of a grandfather.

They say that if you leave a book on a stump at the edge of the property, it will be gone the next day. And in its place, you might find a drawing. A sketch of a bird, or a tree, or an old man with a pipe, drawn with charcoal by a hand that could crush a stone but chooses to create beauty instead.

It is the legend of the Mechanic and the Man of Moss. It is the story of how a man saved a beast, and how the beast became a man, proving to the world that humanity is not a shape, but a choice.

And in the deep woods, where the rain falls like a curtain, the Watcher remains, keeping the memory of his father alive, one page at a time.