The Abandoned Homestead’s Secret: Bigfoot’s Haunting Message About Humanity Revealed in a Chilling Folklore Tale

In the high valleys of the Cascades, where the snow falls so deep it silences the world and the cedar trees grow thick enough to hide a thousand secrets, they tell the story of the Carlson Estate.

It is a story whispered by real estate agents in Cascade Falls and shared by old rangers over bitter coffee. It is the tale of a man who bought a house to be alone, only to find that true solitude is a myth, and that sometimes, the things hiding in the dark are not monsters, but neighbors waiting for an invitation.

The year was 1995, the season was the dying of the light. Trevor Simmons was a man of sixty-four winters, with a heart hollowed out by grief and a bank account filled with the cold comfort of a software fortune. He had spent thirty years building invisible castles of code in the rain-slicked streets of Seattle, but when his wife, Margaret, passed into the long night, the city became a cage of noise and memory.

He sought escape. He sought the “Wood and Stone,” a place far from the “Glass and Wire” of his former life.

He found it in a listing that seemed too good to be true. The Carlson Estate. Forty acres of untamed wilderness, a massive timber-and-stone lodge built in the 1940s by a recluse writer, priced for a quick sale. The heirs of the old writer wanted rid of it; they said it was too far, too cold, too lonely.

Trevor bought it with cash and a handshake, barely looking at the rooms. He drove his truck up the winding dirt track as the November sky turned the color of bruised iron, seeking a silence so profound it would drown out the ringing in his ears.

He did not know that the house already had a keeper.

The lodge was a fortress against the winter. It had a great room with a ceiling high enough for a giant, a fireplace that could roast a whole stag, and a basement that ran the length of the foundation, cut from the living rock of the mountain.

Trevor settled in as the first snows began to fall. He lit fires. He unpacked books. He tried to learn the rhythm of a life without Margaret.

But the house had its own rhythm.

It started with the sounds. In the dead of night, when the wind held its breath, Trevor would hear the floorboards groan overhead. Thump. Thump. Thump. Slow, deliberate steps. Not the skittering of mice, nor the settling of timber. These were the footsteps of weight and purpose.

Then came the open doors. He would latch the heavy oak door leading to the basement kitchen before bed, only to find it standing ajar in the morning, the darkness below breathing cool, earthy air into the warm house.

And then, the smell. It wasn’t the rot of death or the damp of mildew. It was a musk—wild, deep, and ancient. It smelled of wet fur, crushed pine needles, and the deep earth. It was the scent of the mountain itself, concentrated in his living room.

Trevor was a man of logic. He told himself it was drafts. He told himself it was old hinges. He told himself he was an old man alone in a big house, and his mind was playing tricks.

But on the fourth night, he woke to a silence that felt heavy. He walked to the kitchen and found the bread he had baked—a loaf of sourdough left to cool—was gone. In its place, on the center of the table, sat three perfect pinecones, arranged in a triangle.

Trevor stood in the moonlight, his breath hitching. A raccoon steals and leaves a mess. A rat steals and leaves droppings.

Only a person steals and leaves a gift.

He began to hunt, not with a gun, but with his eyes. He explored the house he had bought but never truly looked at.

He climbed to the attic, a dusty cathedral of rafters. There, on the dormer window, he found them: handprints. They were pressed into the grime of fifty years. They were shaped like human hands, but they were massive, the fingers long and thick, the span wide enough to crush a melon.

He went to the basement. He descended the stone stairs into the cool dark. He found the root cellar, the wine racks, the dusty corners. And at the far end, he found a door with a modern padlock hanging open.

Inside was a small room. It was not the lair of a beast. It was the home of a monk.

There were blankets folded with military precision. There were crude bowls carved from maple burl. There were tools arranged by size. And there was a stash of food—dried berries, smoked meat, and the apples Trevor had bought in town.

Someone had been living here. Not for days. The wear on the stone floor, the polish on the wooden tools—it spoke of years. Decades.

Trevor backed out of the room, his heart hammering. He realized then that he was not the owner of this house. He was the roommate.

He could have called the sheriff. He could have bought a gun. But Trevor Simmons looked at the folded blankets and the neat row of tools, and he saw dignity. He saw a life lived in the shadows, surviving on scraps and silence.

He decided to negotiate.

That night, he left a plate of stew and a fresh loaf of bread on the table in the basement room. He left a note, written in block letters: I KNOW YOU ARE HERE. I WILL NOT HURT YOU.

In the morning, the food was gone. The note was untouched. But on the table sat a piece of wood. It was a carving of a bear, whittled from cedar. It was exquisite, capturing the rolling gait and the heavy power of the animal.

The truce was struck.

Winter clamped down on the Cascades. The road became a memory buried under four feet of snow. Trevor and his silent tenant settled into a routine.

Trevor cooked; the tenant ate. Trevor fixed the plumbing; the tenant shoveled the snow from the porch while Trevor slept. They were two ghosts haunting the same castle, circling each other in the dark.

Trevor named him “Krenn,” for the low, rumbling sound he sometimes heard emanating from the basement vents—a sound like stones grinding together deep underground.

They began to communicate. Trevor set up a chalkboard in the basement. He drew a picture of the house. He drew a sun. He drew a question mark.

The next day, Krenn had drawn ten suns, each with five rays. Fifty years.

Trevor sat in the cold basement and wept. Fifty years. This being had come here at the end of the Second World War. He had lived beneath the feet of the writer George Carlson. He had hidden from the heirs. He had watched the world change from the safety of this stone womb.

He was the last of the Old Ones, the Sasquatch, hiding in the house of man because the forest was no longer safe.

Spring arrived with the roar of melting snow. With the thaw came the danger.

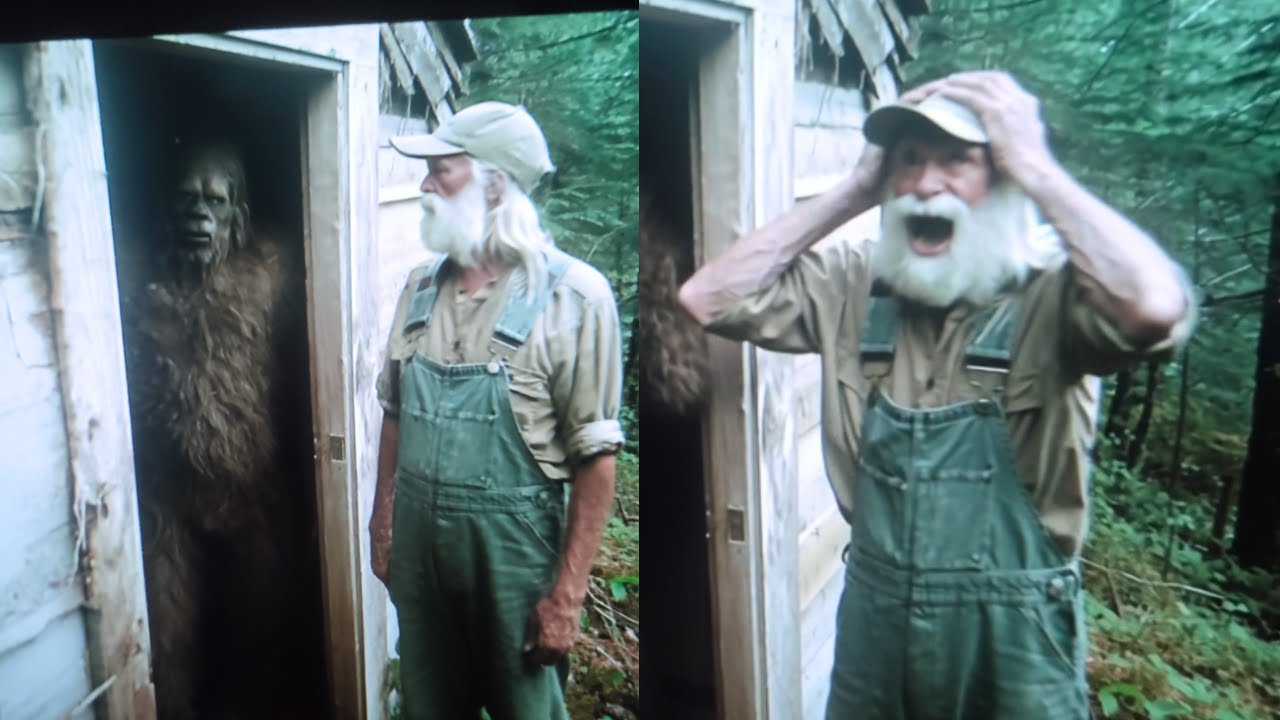

Trevor was in the workshop when he heard voices. He walked out to find four people standing on his land—young, eager, armed with cameras and GPS trackers. They were cryptozoologists, hunters of the unknown.

“We found tracks,” the leader said, his eyes gleaming with the hunger of discovery. “Big ones. Just over your property line. We think he’s close.”

Trevor stood in the driveway, a gray-haired man in a flannel shirt, blocking the path to the house.

“There’s nothing here,” Trevor lied, his voice hard as flint. “Just bears and an old man.”

“We’d like to set up cameras,” the woman said. “Just on the perimeter.”

“Get off my land,” Trevor snarled. “If I see a camera, I break it. If I see you, I call the sheriff.”

He chased them away, but he knew they would be back. The world was shrinking. The shadows were getting shorter.

He went to the basement. Krenn was there, standing in the gloom. For the first time, Trevor saw him clearly in the daylight filtering through the high windows.

He was seven feet of russet-colored fur and muscle. His face was ancient, a map of wrinkles and gray hair. His eyes were dark amber, filled with a terrifying intelligence and a profound, crushing loneliness.

“They are coming,” Trevor said, his voice trembling. “They know.”

Krenn made a sound, a mournful trill. He moved to the chalkboard. He drew a figure running into the mountains. He drew an X over it. He was too old to run. He was too tired to hide in the rain.

Trevor looked at the creature—the person—who had shared his winter. He thought of the carved bear. He thought of the shoveled porch.

“No,” Trevor said. “You are not running.”

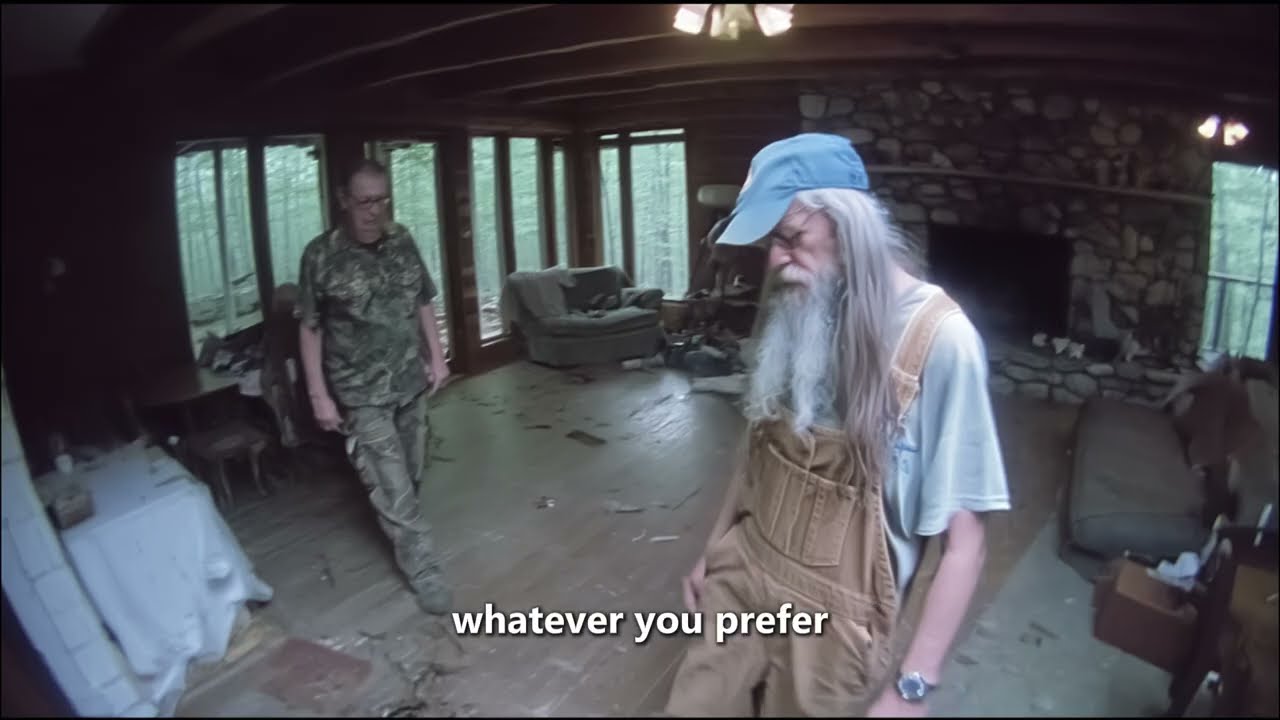

Trevor Simmons called in a favor. He contacted a woman named Dr. Sarah Mitchell, a biologist he had met years ago, a woman known for her discretion and her heart.

“I need you to come,” Trevor told her over the crackling phone line. “I have something that needs protection. Not a specimen. A refugee.”

She came. She sat in the great room as Trevor explained the impossible. And then, Krenn came up the stairs.

He did not crouch. He did not hide. He walked into the room with the dignity of a king in exile. He looked at the woman, and he sat in the armchair opposite her.

Dr. Mitchell wept. She did not measure his skull. She did not ask for a blood sample. She reached out her hand, and Krenn, with infinite gentleness, touched it with one massive finger.

Together, they wove a net of paper and law. They created a “Wildlife Sanctuary” on the deed. They drew up conservation easements that forbade development, logging, or hunting on the forty acres forever. They buried Krenn’s existence in sealed files, classified under “Protected Habitat for Endangered Species,” a legal shield that turned the property into a fortress.

When the hunters returned, they were met not by an angry old man, but by federal signs and the threat of imprisonment. They moved on, looking for monsters elsewhere, never knowing they had walked past a monk.

The years turned like the pages of a book. Trevor and Krenn grew old together.

They stopped hiding from one another. In the evenings, when the sun set the Cascades on fire, they would sit on the back porch. Trevor would smoke his pipe; Krenn would whittle cedar blocks into shapes of deer and eagles.

They did not speak, for Krenn had no words for the things of men, and Trevor had no throat for the rumble of the mountain. But they understood.

They understood that they were both leftovers. Trevor was the debris of a life left behind in the city; Krenn was the echo of a world that had been paved over. They were two shipwrecks who had found each other on the same island.

One Christmas, Trevor came downstairs to find the greatest gift of all. On the mantle, Krenn had placed a carving. It was the house. Every window, every chimney, every shingle was rendered in perfect, loving detail.

And on the porch of the carved house, Krenn had whittled two figures sitting side by side. One large. One small.

They say Trevor Simmons died in his sleep in the winter of 2010. When the sheriff came to collect him, they found the house warm and clean. There was a fire in the grate. There was a fresh loaf of bread on the counter.

But the basement door was locked from the inside.

When they finally broke it down, the room was empty. The blankets were folded. The tools were gone. The chalkboard had been wiped clean, save for a single drawing in the center:

A sun setting behind a mountain.

The heirs sold the property to the state, and it became part of the deep wilderness preserve. The house stands empty now, slowly returning to the earth. The roof is sagging, and the moss is claiming the stone.

But hikers who venture near the old Carlson Estate tell strange stories.

They say that in the dead of winter, when the snow is deep and the wind is howling, you can still see smoke rising from the chimney. They say the porch is always clear of snow, though no one lives there.

And they say that if you leave an apple on the railing, it will be gone by morning. In its place, you might find a piece of cedar, carved with the rough, heavy hands of a friend, shaped like a bear, or a bird, or an old man sitting in a chair, waiting for the sun to rise.

It is the legend of the Silent Tenant, the King in the Basement, who found a home in the house of a man, and proved that even in the wildest places, no one truly has to be alone.