The Astonishing Alcatraz Escape: How Three Convicts Vanished Into the Night—A Daring Prison Break That Remains an Unsolved American Mystery.

They called Alcatraz the Rock, but it was never just a rock. It was a sentence without end, a place where hope went to die. Built on a small island in San Francisco Bay, just 1.5 miles from the mainland, it was close enough to see the lights of the city but far enough that escape seemed an impossible dream. The waters around it were cold and deep, swept by currents that would pull a man under in minutes. The cliffs were sheer. There were no beaches, no places to grab onto. And above it all, the guard towers watched with eyes that never closed.

In 1934, when Alcatraz became a federal penitentiary, it was built to hold the men that the system couldn’t control. Al Capone went there. So did the bank robbers, the gangsters, the repeat escapees—men whose names had become synonymous with defiance. The government understood that some men needed to be kept not just imprisoned, but isolated. Not just locked away, but forgotten.

For nearly three decades, Alcatraz succeeded in its mission. No one escaped. No one even came close. The prison became legend, a symbol of American power, a monument to the idea that there were certain walls that could not be breached.

And then, on a night in June 1962, three men proved that legends could be shattered.

Part Two: The Men Who Dared

Frank Morris was born unwanted and raised forgotten. His parents abandoned him early, and he spent his childhood moving between orphanages and juvenile detention centers. But unlike the other boys who had suffered similar fates, Frank possessed something that could not be taught or inherited: intelligence. When the authorities measured his IQ, the number came back as 133. A genius locked in a criminal’s body. A mind that could have built empires, confined to planning escapes.

John and Clarence Anglin were brothers from rural Georgia, born into poverty and nurtured by rivers. They could swim like fish, move through water like men born to it. They had escaped other prisons before, dragging themselves across freezing rivers with nothing but will and physical capability. They were young, strong, and they understood something that most men never learn: that freedom is worth dying for.

In 1961, these three men met at Alcatraz. They were housed in the same cellblock, separated by concrete walls but united by something more powerful than steel—a shared belief that the impossible could be accomplished.

For six months, they planned. They studied every brick, every ventilation shaft, every guard rotation. They memorized patrol times the way poets memorize verses. They saw the prison not as a final barrier but as materials waiting to be repurposed. They understood that escape from Alcatraz required more than courage. It required intelligence, patience, and a willingness to think beyond the boundaries of what had been tried before.

Part Three: The Tools of Ingenuity

The weapons they gathered were not the tools that prison authorities feared. There were no guns, no explosives, no tools of violence. Instead, they collected raincoats, glue, soap, toothpaste, toilet paper, musical instruments, and an old vacuum cleaner motor.

From dozens of standard-issue raincoats, they carefully cut and pieced together an inflatable raft. Each corner was heated and fused using homemade glue. They created life vests from the same material, waterproof pouches for personal items, and paddles carved from scrap wood. No one suspected anything because they presented themselves as model inmates—musicians who participated in regular prison activities, artists who had been rewarded with access to supplies.

Frank discovered an article in a survival magazine suggesting that raincoats could serve as flotation devices in emergency situations at sea. That single article, read in the prison library during a quiet afternoon, became the foundation of everything that followed.

But the greatest challenge was getting out of their cells. The walls were reinforced concrete, eight inches thick. Digging with spoons stolen from the mess hall seemed futile. But Allen West, the fourth member of the plan, had worked in the kitchen. He secretly removed the motor from a vacuum cleaner, and with it, the group began building a makeshift electric drill by wiring it to their cell’s power source.

Each night, while other prisoners slept, they took turns drilling, widening the ventilation holes beneath their sinks. Holes that led into a hidden utility corridor beneath the cellblock. But the noise of drilling was dangerous. Discovery could come at any moment. And so they solved that problem with elegant simplicity: they played music. During the scheduled recreation hour, when the entire cellblock filled with the sound of guitars and horns played by grateful inmates, that was when the drill came alive. The music was their cover, their camouflage, their protection.

Part Four: The Night of June 11, 1962

The final preparation was the most crucial: creating the illusion of their presence. They crafted dummy heads from soap, toilet paper, cement, and hair collected from the prison barber shop. They painted them with skin-tone pigments extracted from art kits, applied each strand of hair with careful precision, dotted paint onto foreheads and cheeks. When a guard passed by in the darkness, taking only a quick glance into a cell, these dummy heads would appear to be sleeping inmates.

On the night of June 11, 1962, close to midnight, they slipped through the vent holes and crawled along the narrow maintenance corridor behind the cellblock. They made their way to a stairwell that led straight up to the roof. From there, they crossed over the kitchen roof, followed a vent pipe down to the interior courtyard. In their hands were bundles containing the folded raft, homemade paddles, and life vests fashioned from stolen raincoats.

Allen West, the fourth member of their plan, was supposed to join them. But days before the breakout, seized by fear of discovery, he had sealed his vent hole back up with cement. When the night arrived and he tried to chip it away with his bare hands, the layer had hardened. He couldn’t break through in time. And so he remained in his cell, watching as the others escaped into the darkness. He would be the only one to tell the authorities what had happened.

The three men cut through the barbed wire at the top of the perimeter fencing and scrambled down a steep embankment to the water’s edge. They reached the shore around midnight and began their journey across the cold, dark waters of San Francisco Bay.

Part Five: The Silence That Followed

When dawn broke on June 12, 1962, the prison staff came for roll call as usual. The alarm began to blare uncontrollably. Within hours, a massive search operation was launched. Patrol boats circled the island. Helicopters flew low, scanning every ripple, every floating piece of debris. Local radio stations broadcast emergency bulletins non-stop, accompanied by photographs of three inmates now wanted nationwide.

But the perfection of the plan was exactly what made investigation impossible. After ten days of combing every inch of the water, the search teams found only fragments. A drifting paddle, identical to the handmade designs left behind in the cells. A life vest made from raincoats, still fully intact. A waterproof pouch containing family photos, handwritten notes, and contact addresses belonging to the Anglin brothers.

And then—nothing. The searchers waited for bodies to wash ashore, as drowned victims typically do after a few days. But no bodies appeared. No definitive evidence of death. Just absence. Absence and mystery and a question that would haunt America for decades: had they died in the cold waters of the bay, or had they made it to the mainland?

Part Six: The Whispers Begin

The FBI closed its investigation in 1979, concluding that Morris and the Anglin brothers had drowned. The odds were against them, the Bureau said. The waters were too cold, the current too strong, the distance too great. Without bodies as proof, the case was closed. But it was a case that refused to stay closed.

Rumors began to circulate. Some said the brothers had lived in South America, specifically in remote regions of Brazil. Some claimed that Frank Morris had died in 2005, and Clarence Anglin two years later, leaving only John remaining. And in 2013, more than fifty years after the escape, something extraordinary happened.

A letter arrived at the San Francisco Police Department, written in shaky handwriting and signed with the name John Anglin. “We made it out successfully,” the letter read. “Me, Frank, and Clarence. Frank died in 2005. Clarence passed 2 years later. Now only I remain. I have cancer. If you agree to get me medical treatment, I’m ready to turn myself in, but I want no more than one year in prison.”

The police couldn’t verify the sender’s identity. Fingerprints were unclear. There was no envelope, no postmark. Some dismissed it as a cruel hoax. But others heard something genuine in the words—the voice of an old man who had lived a lifetime in hiding and was finally tired.

Part Seven: The Evidence That Cannot Be Dismissed

Then came the photograph.

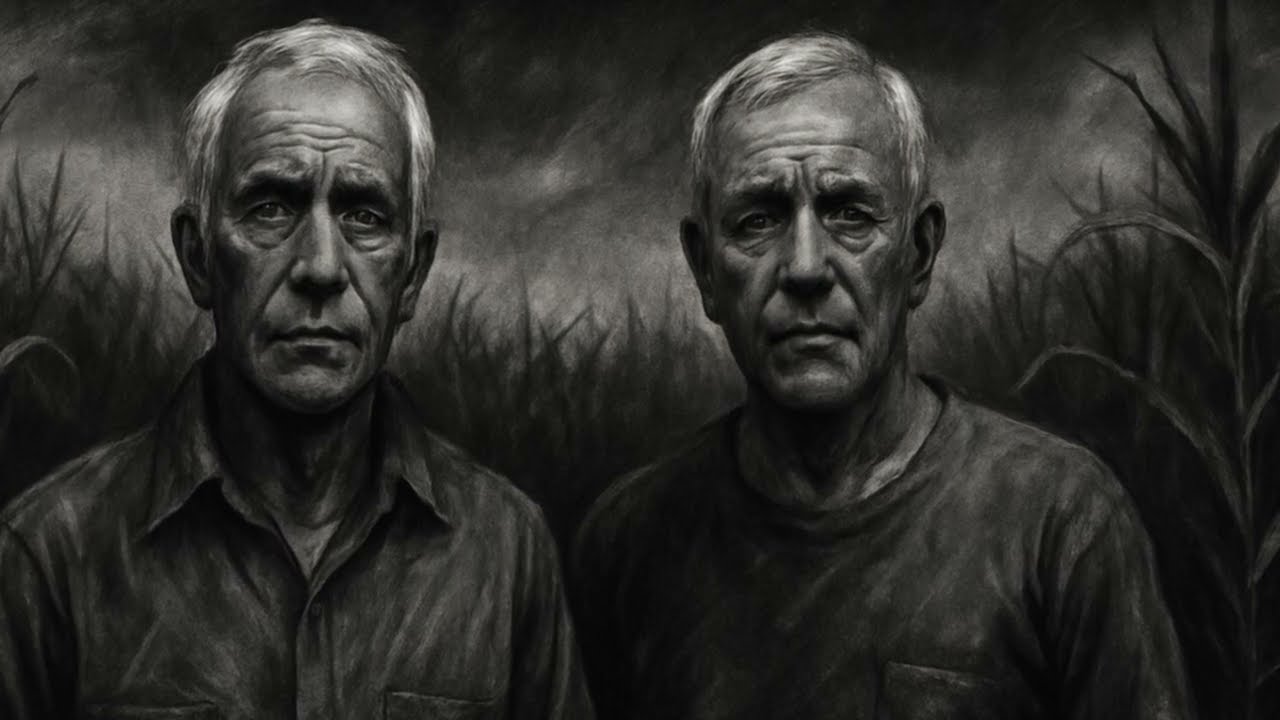

A direct nephew of the Anglin brothers claimed that he had long known the two were still alive. He produced a photograph supposedly taken in 1975, showing two salt and pepper-haired men standing side by side in a sugarcane field in Brazil. Both resembled the age-progressed sketches of John and Clarence Anglin in middle age.

When a team of forensic analysts examined the photograph using facial recognition technology, comparing bone structure, ear shape, and eye position, they concluded that it was highly likely the two men in the image were indeed the Anglin brothers.

The brother of this nephew—who was also the biological sister of John and Clarence Anglin—confirmed something remarkable. For decades after the escape, every Christmas, their family had received cards with no postmark and no return address. But the handwriting was always familiar. It was the handwriting of the two brothers she had known better than anyone else.

Then, when an internal FBI file was declassified, the public learned something startling: as early as 1965, just three years after the escape, the U.S. government had already suspected that all three men had fled to Brazil.

Part Eight: The Living Mystery

Under U.S. federal law, an investigation into a prison escape remains open until all suspects are confirmed deceased or until the year they turn 99. This means that the case of Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers remains technically unsolved. At present, John and Clarence Anglin may be around 93 or 94 years old. Frank Morris, if he is still alive, would be nearing 97.

There are still three to five years before their file is officially closed.

From time to time, someone sends a photograph to the FBI or the San Francisco Police Department. A homeless man in Florida who resembles the age-progressed sketches. An elderly farmer in a quiet Brazilian village. A stranger spotted in Argentina. And someone always asks the same question: Could it be one of them?

Most of these leads don’t produce breakthroughs. The photos don’t match. The timing doesn’t work. The locations don’t make sense. But they persist because this is a story that has never left the American imagination.

Part Nine: The Legend Lives

The 1962 Alcatraz escape has become more than historical fact. It has become legend. It is told in schools and documentaries, in books and movies, in the conversations of people who want to believe that certain kinds of freedom are possible. It represents something fundamental about the American character: the belief that no wall is truly impenetrable, that no barrier is truly insurmountable, that three ordinary men with extraordinary determination can challenge even the most powerful institutions and perhaps—just perhaps—prevail.

The truth about what happened to Frank Morris and the Anglin brothers may never be known with certainty. But in America, that is precisely what makes the story so powerful. In a nation built on the mythology of escape and reinvention, the idea that three men could disappear into the world and live quietly for decades, hidden in plain sight, speaks to something deeper than mere criminal history.

It speaks to freedom itself.

Epilogue: The Ghosts Still Watch

On foggy nights in San Francisco, when the lights of the city blur through the mist and the water seems to blur between solid and liquid, some people say you can still see them. Three figures in a small raft, paddling silently through the darkness. Or perhaps three old men, sitting on a porch in a distant country, remembering a night when they challenged the impossible and won.

The Rock still stands. Alcatraz is no longer a working prison, but a museum where tourists walk the halls and peer into empty cells. The dummy heads are gone. The raincoat raft is gone. The tools are gone. But the memory remains—not as a record of what happened, but as a question about what might have happened.

And in that question lives the American legend. Not the legend of a prison so perfect that it never lost an inmate. But the legend of three men who looked at the impossible and said: not today. Not today will we remain behind these walls. Not today will we accept the sentence. Not today will we be forgotten.

The ocean never gave up its secret. And perhaps it never will.