The Man Who Taught Bigfoot to Write: The Creature’s Shocking Words About Humanity Echo Through Sasquatch Folklore

In the deep, rain-soaked timber of Oregon, where the moss grows thick as a blanket and the silence is older than the roads, they tell the story of the Teacher and the Student.

It is not a story you will find in the history books of Estacada, nor is it written in the ledgers of the forestry service. It is a story whispered by old loggers who have seen things they cannot explain, and by hikers who have found strange marks scratched into the earth near the treeline. It is the tale of Robert Keegan, a man who went into the woods to be alone, and found the one thing he could not teach himself: connection.

Robert Keegan was a man of letters. He had spent thirty years in the classrooms of Portland, teaching the words of Thoreau and Whitman to children who dreamed only of leaving. When his wife, Linda, passed into the long night, Robert packed his books and his grief and moved to a cabin at the end of the world. He sought silence. He sought the company of ghosts.

But the woods are never truly empty.

It began in the autumn of 1994, when the maples turned to fire and the air grew crisp. Robert found scratches in the dirt near his woodpile. They were not the random claw marks of a bear, nor the rooting of a boar. They were deliberate. They were shapes.

H. E. L.

Robert, a man of reason, felt the hair on his arms stand up. He took a stick and completed the word. L. O.

The next morning, the word was gone. In its place was a shaky, backward copy. O. L. L. E. H.

And so, the school began.

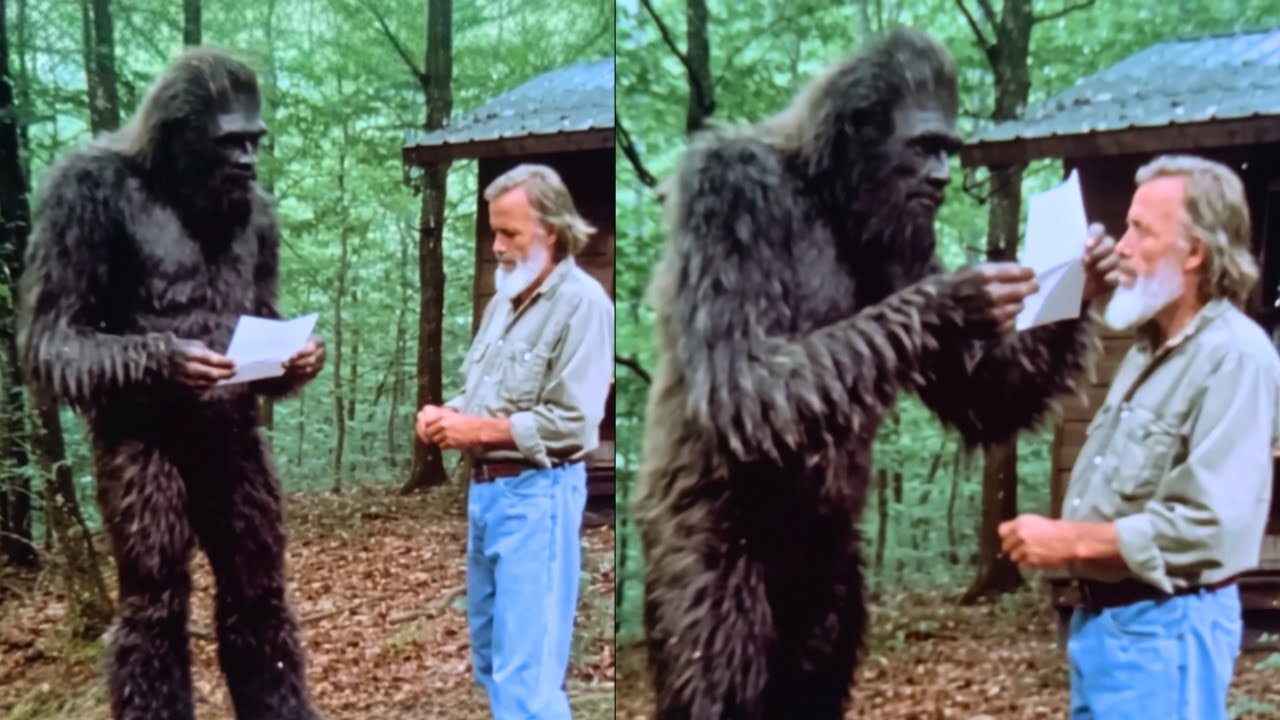

Robert set up a chalkboard in the clearing. He left chalk. He left simple words: TREE. ROCK. SKY.

Every night, the words were copied. Every night, the handwriting grew stronger. The Student was diligent. The Student was hungry.

On a night when the moon was full and bright as a lantern, Robert finally met his pupil.

He was seven feet of shadow and fur. He stood at the edge of the light, a giant woven from the dark fabric of the forest. He was not a man, but his eyes held a spark that Robert recognized instantly—the spark of a mind waking up.

“Hello,” Robert whispered.

The giant stepped forward. He picked up the chalk with fingers the size of sausages, yet with a touch as gentle as a moth’s wing. He wrote: TREE.

He pointed to himself.

“Not yet,” Robert said. “First you learn. Then you choose your name.”

The winter came hard that year, burying the cabin in snow. But the lessons continued. Robert taught verbs. He taught tenses. He taught the difference between want and need.

The Student learned fast. He devoured children’s books, then young adult novels, then the heavy, leather-bound volumes of philosophy Robert cherished.

One night, after reading Of Mice and Men, the Student wrote a question that stopped Robert’s heart.

WHY DID GEORGE KILL LENNIE IF THEY WERE FRIENDS?

They argued about mercy. They argued about love. They argued about the terrible choices that life forces upon the living.

DEATH IS ALWAYS WORSE, the Student wrote. LIFE IS CHANCE. DEATH IS END.

Robert looked at the giant, this lonely king of the woods, and realized he was in the presence of a soul. A soul that had lived in silence for decades, watching the world of men with a mixture of fear and wonder.

As the snow melted and the trilliums pushed through the earth, the Student began to write his own thoughts. He wrote of the forest. He wrote of the stars. And he wrote of humanity.

HUMANS BUILD CITIES TO BE TOGETHER, he wrote. YET HUMANS ARE LONELY. WHY?

I AM ALONE, he continued. BUT I AM CONNECTED. TO TREE. TO DEER. TO WIND. HUMANS ARE DISCONNECTED.

Robert transcribed these words into notebooks. He felt the weight of them. Here was a critique of civilization from a being who had never set foot in a city, yet understood its failures better than its architects.

But the world of men is jealous of its secrets.

Rumors began to spread in town. People talked of strange lights at the Keegan place. They talked of voices in the night. A neighbor, Tom Brewster, warned Robert that the town thought he was going mad.

“The woods keep secrets,” Tom said. “But not forever.”

Then came the scientists. Dr. Helen Cartwright, a woman with sharp eyes and a folder full of photographs, came to the cabin. She had pictures of footprints. She had DNA samples that defied classification.

“We know something is here,” she said. “We have cameras. We have drones.”

Robert knew the time of the chalkboard was ending. The time of the cage was beginning.

He went to the Student. He explained the drones. He explained the thermal cameras that could see heat through the trees.

HOW LONG? the Student wrote.

“Spring,” Robert said. “When the snow melts.”

THEN WE DECIDE, the Student wrote. HOW STORY ENDS.

They made a plan. It was a dangerous, desperate plan. They would not wait to be found. They would introduce themselves.

Robert called Dr. Cartwright back. He called a lawyer. He called a philosopher. He called a journalist. He gathered a council of the wise and the brave.

On a morning in February, when the frost lay silver on the pines, the council gathered at the cabin. They stood on the porch, shivering in the cold.

“You are not here to discover a monster,” Robert told them. “You are here to meet a person.”

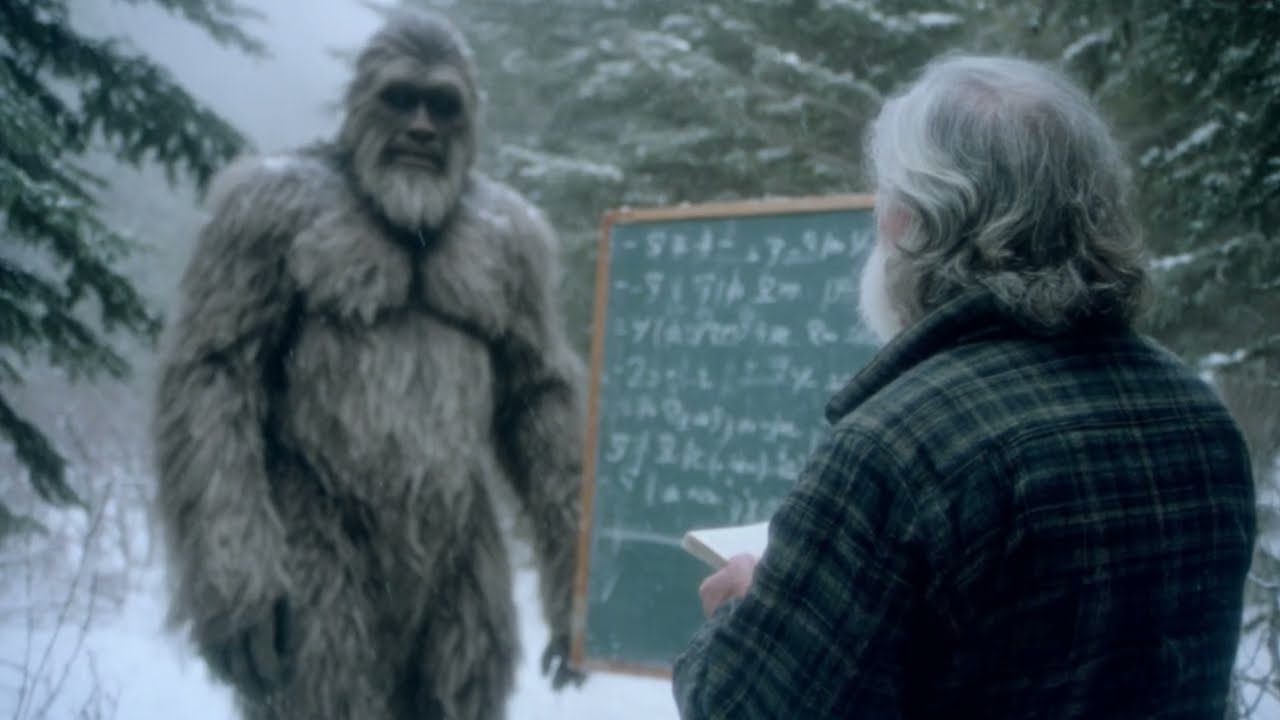

The Student stepped out of the trees. He did not roar. He did not pound his chest. He walked to the chalkboard, picked up the chalk, and wrote:

MY NAME IS MOSS.

I AM PLEASED TO MEET YOU.

The silence that followed was louder than any scream. The scientists stared. The lawyer wept. The journalist forgot to take notes.

Moss wrote for hours. He answered their questions. He explained his life. He explained his fear.

I AM AFRAID HUMANS WILL SEE ANIMAL, he wrote. I AM AFRAID OF CAGE.

“We will not let them cage you,” the lawyer promised. “We will fight.”

And they did.

They built a fortress of words and laws around Moss. They argued for personhood. They argued for rights. They turned the legal system into a shield for the giant in the woods.

It wasn’t perfect. The world is cruel, and there were those who wanted to hunt him. But Moss was no longer a myth. He was a plaintiff. He was an author. He was a voice.

Robert Keegan grew old. His heart grew weak, his hands shook, but his spirit was full. He had done the one thing a teacher dreams of: he had given his student a voice, and the student had used it to change the world.

One evening, as the sun set behind the Cascades, Robert sat on his porch. Moss sat beside him, whittling a piece of cedar.

“Was it worth it?” Robert asked, his voice thin as paper. “To be known?”

Moss stopped carving. He picked up the chalk and wrote on the slate he always carried.

BEFORE, I WAS SHADOW. NOW, I AM MOSS.

YOU GAVE ME NAME. YOU GAVE ME WORLD.

Robert smiled. He closed his eyes, listening to the wind in the trees, the wind that connected everything—the man, the giant, the forest, the stars.

They say Robert Keegan passed away in his sleep that winter. When they found him, the cabin was cold, but his notebooks were neatly stacked on the table.

And on the chalkboard in the clearing, written in a heavy, deliberate hand, were the words:

TEACHER IS GONE. BUT LESSON REMAINS.

LIFE IS CONNECTION.

DO NOT BE ALONE.

Moss is still out there, they say. He lives in the deep woods, protected by the laws of men and the silence of the trees. He writes his thoughts on stone and bark, a philosopher king in a kingdom of green.

And sometimes, if you hike deep enough into the Oregon timber, you might find a chalkboard nailed to a tree. And if you leave a piece of chalk, and a question, you might just get an answer from the Scholar in the Woods.