The shocking reason why Jack the Ripper was never caught—unsolved mysteries, hidden clues, and dark secrets that kept history’s most infamous killer in the shadows.

The fog that rolled through the streets of London on the morning of August 31, 1888, was not unusual. What was unusual was the body that Charles Cross discovered lying in the gutter on Buck’s Row, still warm, still bleeding. Mary Ann Nichols—known to some as Polly, to others merely as another nameless woman selling her body for the price of gin and a room for the night—had become something else entirely. She had become the first.

Inspector Edmund Reid stood over the body as the morning light struggled to penetrate the perpetual haze of Victorian London. He was an experienced officer, had seen his share of East End violence. But something about this body troubled him. The throat had been cut with such precision, the wound so deep, that it had nearly severed the head from the shoulders. And below the dress, the abdomen had been opened in a manner that suggested not the frenzied attack of a common drunk, but the careful, deliberate work of someone who knew exactly where to cut.

Reid noted the lack of blood spatter. The killer had been controlled, methodical. Whoever had done this had not panicked. They had not run. They had worked with the confidence of someone who knew they would not be interrupted.

Within days of Nichols’s murder, another body appeared. Annie Chapman, 47 years old, was discovered in the backyard of 29 Hanbury Street. Like Nichols, her throat had been cut deeply. But this time, the killer had gone further. The womb had been removed with surgical precision. Reid studied the autopsy report with growing unease. This was not the work of a street criminal. This required knowledge—anatomical knowledge that most men did not possess.

Over the following weeks, the murders accelerated. Elizabeth Stride on September 30. Catherine Eddowes, on the same night, less than an hour later. And then, on November 9, Mary Kelly—young, beautiful Mary Kelly, only 25 years old—was found in her room at Miller’s Court, so thoroughly mutilated that even the seasoned police photographers struggled to maintain their composure.

Five victims in less than three months. The canonical five, as they would come to be known. Five women whose names would echo through history, not because they were important, but because of how they died.

Part Two: The Investigation That Failed

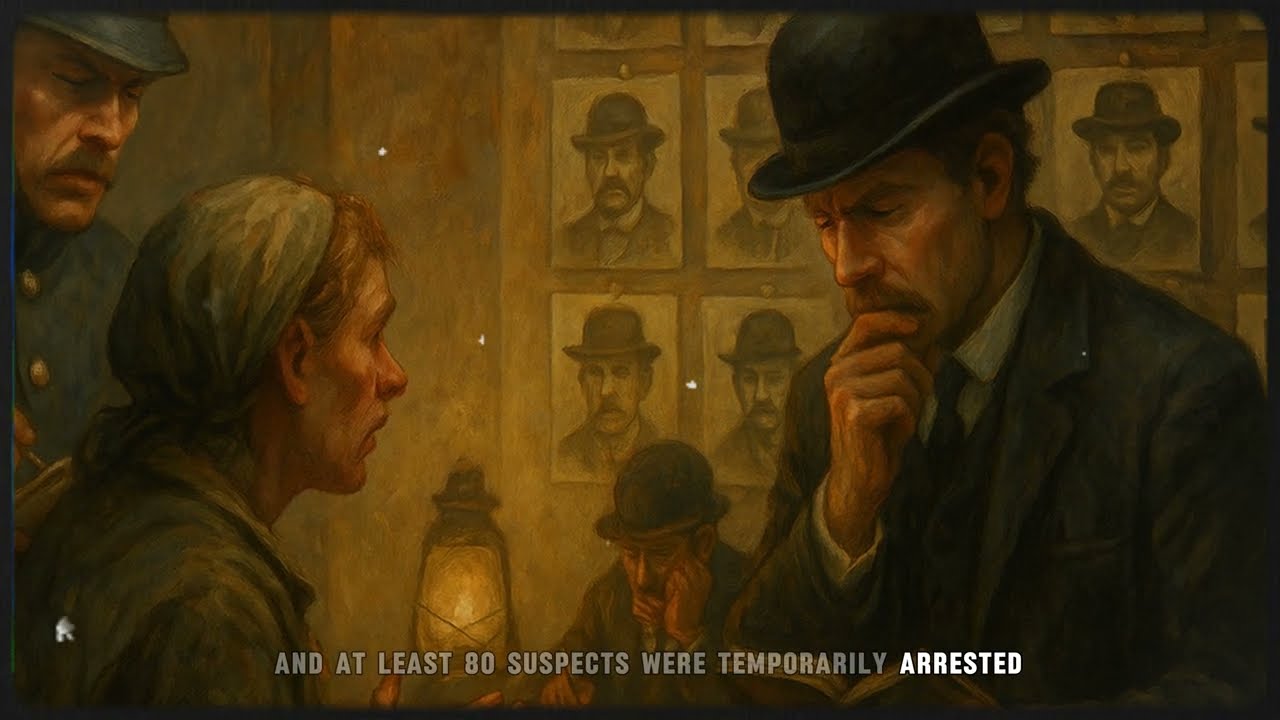

By November 1888, the Metropolitan Police had assembled what was, for the time, an unprecedented investigative force. More than 2,000 individuals had been questioned. Over 300 had been placed under surveillance. At least 80 suspects had been arrested and interrogated. Officers searched homes, boarding houses, every alley and corner of the East End. They offered rewards, appealed for public cooperation, and threw themselves into the hunt with an intensity that bordered on desperation.

Chief Inspector Frederick Abberline, a man whose reputation had been built on solving cases others considered unsolvable, found himself facing an adversary unlike any he had encountered. The killer seemed to possess an almost supernatural ability to vanish. He struck in narrow alleys and tightly packed slums where residents kept to themselves, where curiosity could be dangerous. After each killing, he simply disappeared, leaving no trace beyond the mutilated bodies and the questions that multiplied with each new discovery.

The police focused on men with anatomical knowledge. Surgeons. Medical students. Butchers. They investigated anyone with access to sharp instruments and an understanding of human anatomy. They tracked men who had been arrested for indecent assault. They investigated known violent criminals. They questioned asylum inmates released around the time of the murders.

Yet nothing came together. Witnesses provided contradictory descriptions. Evidence was contaminated or lost. Leads went nowhere. The killer seemed to anticipate the police’s movements, always staying one step ahead.

Detective Sergeant William Thick, known for his knowledge of East End criminals, made an arrest in September. John Pizer, a man known as “Leather Apron,” was dragged into custody amid public hysteria. But Pizer’s alibis held up. A pub owner confirmed he had seen a man with bloodied clothes the morning Annie Chapman’s body was found, but that man was not Pizer. Within days, he was released. The hysteria that had built up around his arrest deflated, replaced by a deeper sense of hopelessness.

Part Three: The Suspects

As the weeks turned to months and the months turned to years, a growing list of suspects emerged. Some were investigated by police at the time. Others surfaced decades later through the research of amateur historians and criminologists who had become obsessed with solving what Scotland Yard could not.

Montague John Druitt was one of the earliest and most intriguing suspects. A barrister and schoolteacher, Druitt had struggled with mental health issues throughout his life. In December 1888, just weeks after the final canonical murder, his body was discovered floating in the River Thames. The circumstances were suspicious. Weights had been tied to his body, suggesting suicide. The timing was too convenient, the method too deliberate. Many theorists concluded that Jack the Ripper had ended his own life, unable to live with the weight of his crimes.

Severin Klosowski, a Polish immigrant who anglicized his name to George Chapman, lived in Whitechapel during the murders. He worked as a barber and later posed as a doctor. But his murderous career had not ended with the Ripper murders. Between 1900 and 1902, he poisoned three of his wives, using a different method but displaying the same callous disregard for human life. Chapman was eventually hanged in 1903, but whether he was also Jack the Ripper remained a matter of speculation.

Michael Ostrog, a professional criminal with a record of fraud and theft, had once impersonated a military doctor and spent time in mental hospitals. The police had considered him seriously, and his name appeared on lists of suspects. But his records were riddled with inconsistencies. There was no definitive evidence placing him in London during the murders.

Aaron Kosminski represented something different. A Polish barber living in Whitechapel during the time of the murders, Kosminski was later institutionalized for mental illness. In 2014, more than a century after the crimes, a DNA study was conducted on a shawl allegedly belonging to one of the victims. The results showed a genetic match with Kosminski’s descendants. For the first time in the history of the case, there was a piece of physical evidence linking a suspect to the crime. Yet even this breakthrough came with caveats. The chain of custody for the shawl was unclear. The DNA results were questioned by other experts. The mystery remained unresolved.

And then there was Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence—a grandson of Queen Victoria himself. The theory that the Ripper was a member of the royal family had emerged almost immediately after the murders and had never entirely disappeared. The prince was rumored to have suffered from syphilis, which some claimed led to madness. One elaborate theory suggested that the Ripper murders were covered up at the highest levels of power and that if the prince were revealed to be the killer, it would have triggered an unprecedented political crisis. But historians had largely dismissed this theory, citing evidence that placed Prince Albert Victor outside of London during the time of the killings. The question remained: if not the prince himself, then had someone powerful protected the killer?

Part Four: A Society of Secrets

To truly understand why Jack the Ripper was never caught, one had to understand the society in which he operated. Victorian London was a city of profound contradictions. Grand architecture and impeccable fashion existed alongside desperate poverty and brutal violence. The wealthy lived in comfortable ignorance of the conditions in the East End, where thousands of poor laborers, immigrants, and society’s outcasts crowded into squalid tenements.

Immigrants, particularly those from Eastern Europe and the Jewish communities, had become convenient scapegoats for the city’s problems. They were accused of stealing jobs, overcrowding housing, and bringing crime. In this atmosphere of xenophobic fear, the police found it convenient to focus their suspicions on foreign-born residents. Aaron Kosminski was questioned partly because he was an immigrant. George Chapman was investigated partly because he was Polish. The bias of the investigation itself may have obscured the true killer while directing attention toward the already marginalized.

The victims themselves were considered unworthy of serious protection. They were sex workers, women who had been abandoned by their husbands or had never married, women who had turned to prostitution out of desperation. In the eyes of respectable Victorian society, they were not innocent victims but rather symptoms of moral decay. The newspapers that covered the murders mixed sensationalism with subtle condemnation. The killer was hunted not because he had murdered poor women, but because he had dared to operate in London itself, threatening the illusion of order that the city maintained.

The police force itself was struggling. There were no fingerprint databases. Crime scene preservation was haphazard at best. Witness testimonies were unreliable, sometimes contradictory. Detectives relied almost entirely on catching someone in the act or securing a confession. They had no tools for psychological profiling, no methods for analyzing physical evidence systematically. They were, in many ways, as helpless as the city itself.

And perhaps most importantly, they lacked the cooperation of the very people who might have provided information. The residents of Whitechapel had learned long ago not to trust the police. Many had experienced police brutality. Others had seen justice fail repeatedly. Some feared retribution. In such conditions, potential witnesses remained silent, and the killer operated in a landscape of selective blindness, where people saw what they wanted to see and forgot what they chose not to remember.

Part Five: The Mystery Deepens

By 1891, the murders had stopped. The killer, if he was a single person, had simply vanished. No one knew if he had died, moved away, or been imprisoned for some other crime. The investigation, once so intense and consuming, gradually wound down. The case remained officially open, but it was clear that there would be no arrest, no trial, no final answer.

The mystery that followed the cessation of the murders was almost as disturbing as the murders themselves. Why had the killer stopped? Had he been caught for another crime? Had he died? Had he achieved whatever twisted satisfaction he sought and simply moved on? Or—and this was perhaps the most unsettling possibility—had he never stopped at all, but merely moved to a different location where his crimes went unrecognized?

Over the subsequent decades and centuries, the case of Jack the Ripper became something more than a historical puzzle. It became a cultural obsession. Each generation added its own theories, its own suspects, its own interpretations. Amateur historians compiled evidence. Television documentaries explored possibilities. DNA studies were conducted. Books were written. Yet with each new theory came new contradictions, new questions, new dead ends.

The case revealed something fundamental about the limits of justice and the human need for resolution. A crime this savage, this brazen, this successful in evading capture, seemed impossible in a rational world. And so people invented explanations—royal conspiracies, medical geniuses, supernatural agents—anything to impose order on a mystery that stubbornly refused to be solved.

Part Six: The Legacy

What made Jack the Ripper different from other serial killers was not the number of his victims, which was relatively small compared to later murderers. Rather, it was the combination of several factors: the precision of his crimes, the urban setting that fascinated the modern imagination, the failure of police to catch him, and the tantalizing lack of resolution.

The Ripper murders occurred at a moment when photography was becoming widespread, when newspapers could publish detailed accounts of murders to a literate public, when cities were beginning to feel like they were coming unraveled under the pressure of industrialization and rapid social change. The case became a symbol of urban anxiety, of the fear that civilization was merely a thin veneer covering darker truths.

In the end, no one was definitively proven to be Jack the Ripper. The killer’s identity remained unknown. The case closed without resolution. But perhaps that was precisely what made the case so enduring, so resonant, so persistently fascinating. In a world that demands answers, a mystery that refuses to provide them becomes a kind of eternal provocation.

Whitechapel remained. London remained. The fog continued to roll through the streets. But Jack the Ripper—the phantom who had walked those streets in 1888—remained forever unknown, forever elusive, a figure of mystery and terror who had slipped through the hands of justice and vanished into history, leaving behind nothing but questions and the haunting knowledge that sometimes, evil can operate with impunity, protected not by supernatural powers or royal privilege, but simply by the ordinary limitations of human society and the willingness of that society to let certain crimes go unsolved.