What was sex really like in the Middle Ages—unsolved mysteries, forbidden desires, and hidden truths about love, passion, and taboo in a bygone era.

Brother Thomas was dying. The monastery physician, Brother Anselm, knew it with the certainty that came from thirty years of observing the human body’s rebellion against the soul’s demands.

“His humors are imbalanced,” Anselm explained to the Abbot, carefully choosing his words. “The heat builds in his head. His mind wanders. Without release, the pressure will rupture his very being.”

The Abbot nodded solemnly. “He has taken vows of celibacy. He must endure.”

But Anselm had witnessed too many such deaths. Young men, brilliant scholars, devout believers—all destroyed by the contradiction that lay at the heart of medieval Christianity. The Church insisted that abstinence was holy. Yet the body itself, that flesh that supposedly should be subdued, screamed its own truth: abstinence killed.

In 1287, King Louis VI had died after refusing his wife during the Albigensian Crusade. One hundred thousand crusading soldiers had perished not from battle, but from the slow decay that came when the body’s natural functions were denied in the name of God. And now Brother Thomas lay in the infirmary, his body turning against itself, consumed by the very purity the Church demanded.

“Give him permission,” Anselm said quietly. “Let him take a woman, even once. It will save his life.”

“I cannot,” the Abbot replied. “Such a thing would condemn his soul.”

Anselm wanted to ask which mattered more—the soul or the body. But he knew better than to voice such heresy.

Part Two: The Hidden Knowledge

That night, Anselm visited Brother Thomas in secret. He brought with him knowledge that the Church would have deemed witchcraft, tools that physicians had learned through centuries of observing reality rather than doctrine.

“There is a way,” Anselm whispered. “One that requires no violation of your vows, yet provides relief.”

Thomas looked at him with desperate, fevered eyes. “What way?”

Anselm explained what the medical texts called a necessary treatment. What the confessors called mortal sin. What the body recognized as survival.

In the darkness of the monastery, Anselm helped his patient find release from the unbearable pressure that threatened to destroy him. It was clinical, efficient, and by morning, Thomas’s fever had broken.

The Abbot never knew. But the contradiction remained, written in Thomas’s recovered pulse and Anselm’s troubled conscience.

Part Three: The Woman’s Choice

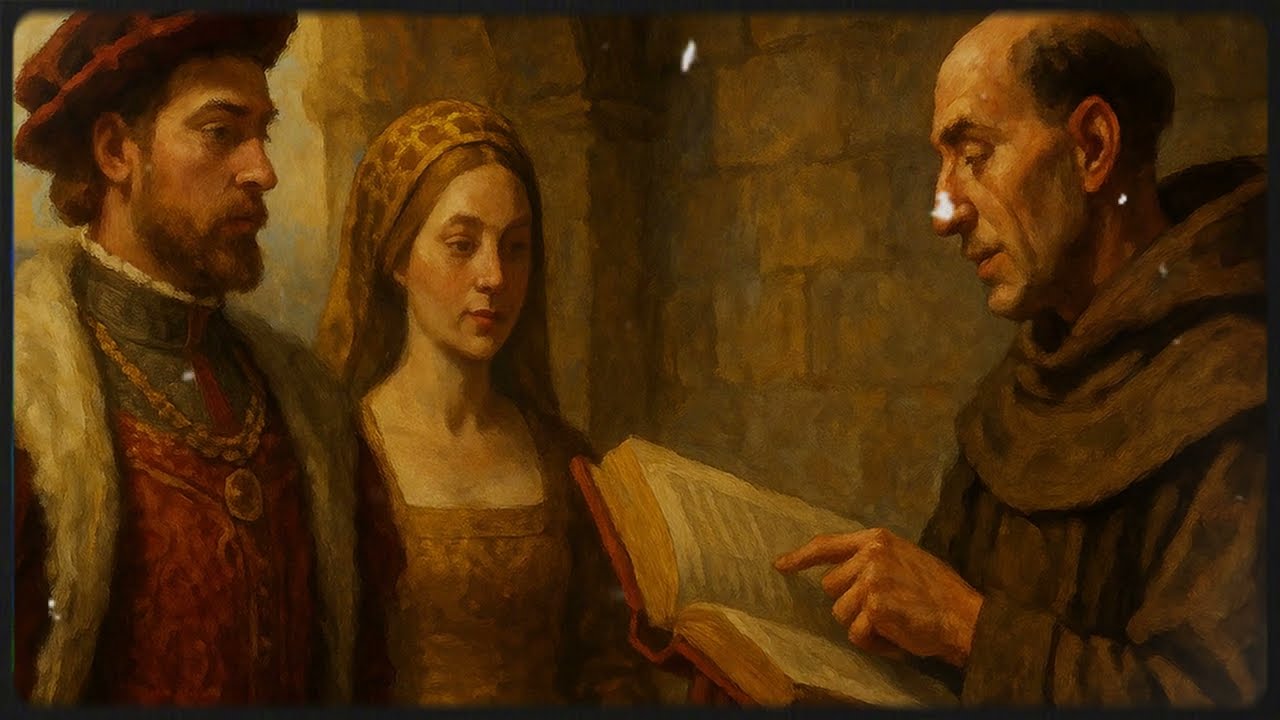

Three cells away, a different struggle was occurring. Marjery Kempe—visiting the monastery for spiritual counsel—knelt before the Abbot with a request that violated every principle of wifely obedience.

“I wish to live in celibacy within my marriage,” she announced.

The Abbot was stunned. Fourteen children she had borne. Fourteen times she had submitted to her husband’s rights. Fourteen times her body had paid the price.

“It is your duty,” the Abbot began, but Marjery interrupted.

“My duty is to God. I have given the world its heirs. Now I wish to give my soul its salvation.”

She would negotiate with her husband later, in the market, offering him an impossible choice. Would he prefer to see her dead? Or would he accept celibacy in exchange for her remaining his wife in every other way—sharing meals, repaying debts, maintaining the appearance of marriage without its flesh?

John Kempe chose the latter. And in that choice, a medieval woman secured what should have been impossible: control over her own body.

Part Four: The Paradox

That same afternoon, a young knight arrived at the monastery gates, carrying verses about a lady he could never touch. Courtly love, they called it—a love so refined it required that it never be consummated. He would compose poetry, perform heroic deeds, and die with his desire forever unfulfilled, because such suffering proved the purity of his affection.

The Abbot approved of this completely. A love that transcended the flesh, the spiritual ideal made manifest.

Yet in the infirmary, Brother Thomas recovered from the physical relief that had saved his life—an act the same Abbot would have condemned as sinful.

The contradictions were everywhere, layered and inescapable. The Church taught that virginity was sacred, yet prescribed that women who felt the pressure of their “female essence” be treated by physicians who stimulated them to release. It condemned masturbation as sinful, yet prescribed it as medicine. It celebrated celibacy as holy, yet watched thousands die from the biological impossibility of denying their fundamental nature.

Conclusion: The Truth Between

As Anselm grew older, he came to understand that medieval sexuality was never about morality. It was about power—the power of the Church to control bodies, to define sin, to determine who could touch whom and under what circumstances.

But beneath that power structure, humans endured. They negotiated. They found secret ways to survive. Marjery secured autonomy. Thomas received healing. Knights composed love that would never be consummated, finding in that very impossibility a kind of freedom.

The contradiction between doctrine and lived reality was not a flaw in the system. It was the system itself—a tension that allowed people to survive even as they lived under the Church’s absolute authority.

In the gap between what the Church demanded and what the body required, medieval men and women found small spaces of resistance, moments of grace, paths to survival.