September 14th, 1943. Northern Italy. The sound that haunted every Allied soldier’s nightmares. The bone rattling 1200 rounds per minute scream of the German MG42. Vermach Doctrine called it the buzzsaw. The weapon that could cut down entire squads in seconds. But in a small British position overlooking the Gothic line, Sergeant Charles Baines gripped something the Germans had dismissed as pathetically slow.

The Bren Light machine gun, 500 rounds per minute, half the firepower, a quarter, the terror. Everything military wisdom said would get you killed against Hitler’s buzz saw. Through his iron sights, Baines watched three MG42 teams setting up their deadly crossfire. Their crews confident, their doctrine proven, their high-speed death machines ready to unleash hell.

Then Baines did something that defied every rule of machine gun warfare. He squeezed his trigger. Once, twice, three precise bursts. When the smoke cleared, the silence was deafening. Three MG42 teams gone. The weapon everyone said was too slow had just rewritten the rules of war. The cacophony of war thundered across the Italian countryside as Lieutenant Colonel John Bren hunched over technical drawings in a cramped field workshop.

His weathered hands tracing the blueprint lines of what many considered an engineering failure. Outside, the familiar death rattle of German MG-42s echoed through the valleys. 1,200 rounds per minute of pure terror that had carved vermach superiority into the bones of every Allied soldier who had survived their first encounter with Hitler’s buzz saw.

Bren’s creation lay disassembled on the workbench before him, its components gleaming dullly in the lamplight. the Brenite machine gun, 500 rounds per minute, 22 pounds of British engineering that his own superiors had initially dismissed as inadequate for modern warfare. While German doctrine preached the gospel of overwhelming firepower, suppressed the enemy with volume until they couldn’t lift their heads, Bren had committed what many considered tactical heresy.

He had designed a weapon that fired slowly. The engineers fingers moved methodically across the weapon’s closed bolt mechanism, a design choice that flew in the face of conventional machine gun wisdom. Every military expert knew that machine guns should fire from an open bolt. It prevented cookoffs from overheated chambers and allowed for sustained fire.

But Brent had calculated differently. The closed bolt system meant the first shot from his weapon would strike exactly where the gunner aimed, not somewhere in the general vicinity like the spray and prey approach. favored by high cyclic rate weapons. Major Edward Armstrong ducked into the workshop, mud caked on his uniform and concern etched across his face.

The distant thunder of artillery had been growing closer all morning, and British positions along the Gothic line were reporting increasingly aggressive German probes. “The men are asking questions, Colonel,” Armstrong said, settling his weight against the doorframe. They’ve heard about your gun, but they’re seeing what the MG42 teams do to our boys.

1,200 rounds per minute versus 500 doesn’t sound like winning odds. Bren looked up from his work, his eyes holding the quiet confidence of a man who had done his calculations twice, and trusted the mathematics over popular opinion. Tell me, Major, what good are, 1200 rounds per minute if only one in 20 finds its target? He lifted the Bren’s barrel, noting the chromeplated bore that would maintain accuracy even after thousands of rounds.

The Germans are fighting yesterday’s war with today’s technology. They think volume equals victory. Armstrong shifted uncomfortably. He had seen the devastating effect of German machine gun nests firsthand. Entire companies pinned down by single MG42 teams unable to advance or retreat under the withering curtain of lead. With respect, Colonel, “Suppression works. Their doctrine works.

Our boys can’t move when those buzzsaws open up.” “Suppression is a luxury,” Bren replied, his voice carrying the weight of hard-earned battlefield wisdom. It requires ammunition, time, and the assumption that your enemy won’t shoot back accurately while you’re hosing down the landscape. He began reassembling the weapon with practiced efficiency.

Each component sliding into place with mechanical precision. My gun doesn’t suppress, it eliminates. The conversation was interrupted by the arrival of Sergeant Charles Baines, a weathered paratrooper whose calm demeanor masked years of combat experience across North Africa and Sicily. Behind him walked Corporal Alfred Jenkins, younger but equally steady, his eyes holding the particular alertness of a soldier who had learned to read battlefields like other men read newspapers.

Both men had volunteered to test Bren’s creation under actual combat conditions, a decision that had raised eyebrows throughout the regiment. “Begging your pardon, sir,” Bane said, nodding to both officers. “We’ve had word from the forward observers. Jerry’s moving up three MG42 teams to that ridge line overlooking our supply route.

Command wants to know if your gun is ready for a proper test.” Bren’s hands stilled on the weapon. This was the moment he had calculated for, planned for, built toward through months of design refinements and ballistic testing. The Bren LMG represented everything his engineering philosophy stood for.

Precision over power, accuracy over volume, intelligent design over brute force. But philosophical victories meant nothing if soldiers died proving them. “The weapon is ready,” he said quietly. The question is whether we are. Jenkins spoke up, his voice carrying the practical wisdom of an experienced gunner’s assistant. Sir, we’ve run the drills.

Barrel changes in under 5 seconds. Magazine swaps in three. The gun handles like a rifle until you need it to be a machine gun. He paused, then added with characteristic understatement. Charlie here can put five round bursts through a dinner plate at 200 m. Bane’s nodded. Confirmation. The sight picture stays true, Colonel.

First shot hits where you’re looking, and the follow-ups stay group tight. Can’t say the same for weapons that jump around like angry cats when they fire. Armstrong studied the three men. The engineer, who had bet his career on unconventional wisdom, and the soldiers willing to stake their lives on his calculations. The German teams will have overlapping fields of fire.

Standard MG42 doctrine calls for one gun to suppress while the others relocate. If your theory is wrong, then good men die for my mistakes, Bren finished. But if conventional wisdom was correct, Major, we wouldn’t need new weapons. We just need more of the old ones. He lifted the completed Bren LMG, feeling its balanced weight.

22 pounds of precision engineering that represented everything he believed about the future of infantry warfare. The Germans think machine guns are aerial weapons. Spray enough bullets and eventually you’ll hit something important. I’ve designed a point weapon. Every shot deliberate, every burst calculated. The sound of approaching vehicles cut through their conversation.

A dispatch writer appeared at the workshop entrance, his face grim with the particular urgency that preceded combat operations. Colonel Bren, Major Armstrong, you’re wanted at forward command immediately. The German advance has accelerated. Those MG42 positions need to be neutralized within the hour or our entire defensive line becomes untenable.

As the four men gathered their equipment, the distant sound of the German buzz saws intensified. their high cyclic terror song echoing off the Italian hills like some mechanical death hymn. Bren shouldered his creation, feeling the weight of two years of design work and a lifetime of engineering principles.

In moments his slow gun would face the fast death of Vermach doctrine. The outcome would determine not just tactical success, but whether precision could triumph over power in the brutal arithmetic of modern warfare. The test was about to begin. The forward observation post offered a clear view of the German positions, and through his field glasses, Major Armstrong could see why conventional tactics had failed so completely.

Three MG42 teams had established themselves in a textbook defensive triangle on the ridge line, each position carefully cited to provide mutual support while covering the critical supply route below. The lead team occupied a reinforced bunker at the apex, while the two supporting positions flanked it at distances of roughly 150 m.

Close enough for coordinated fire, but far enough apart to prevent a single mortar round from eliminating multiple guns. Sergeant Bane studied the terrain with the practiced eye of a veteran machine gunner, noting the fields of fire and likely approach routes. The German positions commanded every avenue of advance, their overlapping sectors creating a killing zone that stretched nearly 800 meters across the valley floor.

“Standard Vermach deployment,” he murmured to Jenkins. “Primary gun suppresses while the others reposition. They’ll keep at least one barrel hot at all times.” Colonel Bren crouched beside his testing team, the Bren LMG cradled across his knees as he analyzed the tactical problem. The German doctrine was sound. Overwhelming firepower applied continuously to deny movement to enemy forces.

An MG42 team could sustain 1,200 rounds per minute for extended periods. Changing barrels when overheating threatened to damage the weapon. The sheer volume of lead created an almost impenetrable wall of death that had stopped every British advance for the past 3 days. They’re confident, Armstrong observed, watching through his binoculars as German soldiers moved casually between positions.

No camouflage discipline, minimal cover. They know our boys can’t get close enough to engage effectively. Jenkins checked the Bren’s magazine, noting the distinctive curved design that fed smoothly from the top-mounted position. The 30 round capacity seemed pathetically small compared to the beltfed systems of the German weapons, but Bren had insisted that magazine feeding provided crucial advantages in sustained fire scenarios.

Quick reloads, no belt jams, and most importantly, the ability to control burst length precisely rather than relying on trigger discipline to prevent runaway guns. The first test came when a British patrol attempted to cross the valley floor at its narrowest point. The lead MG42 opened fire immediately. Its distinctive sound tearing through the morning air like ripping canvas amplified a thousandfold.

1,200 rounds per minute created a continuous stream of tracers that seemed to paint deadly lines across the landscape. The patrol scattered, diving for whatever cover they could find as bullets chewed chunks from rocks and trees around them. Baines watched intently as the German gunner traversed his fire across a front of nearly 200 m, hosing down every potential hiding spot with methodical thoroughess.

The second and third MG42 teams remained silent, conserving ammunition while their comrade suppressed the British soldiers. It was textbook application of machine gun doctrine. One gun fires while others wait, creating the illusion of continuous coverage while managing heat buildup and ammunition consumption.

Look at the pattern, Bren said quietly, his engineer’s mind analyzing the tactical display. 800 rounds expended to pin down six men. Effective suppression, but at what cost? He pointed toward the German position where soldiers were already preparing a fresh barrel for the overheated weapon. Every sustained burst requires a barrel change.

Every barrel change creates a window of vulnerability. The German efficiency was impressive. The barrel change took less than 10 seconds, accomplished while the gunner’s assistant fed a fresh ammunition belt into the weapon. But Bren had noted something crucial. During those 10 seconds, the entire sector of fire remained uncovered.

The supporting MG42 teams maintained their silence, trusting in their doctrine that suppression from a single weapon was sufficient to control the battlefield. Armstrong called for artillery support, hoping to suppress the German positions long enough for the trapped patrol to withdraw. British 25p pounder guns responded with a concentrated barrage that sent geysers of earth skyward around the ridge line.

The German team simply withdrew deeper into their reinforced positions, weathering the bombardment with the patience of experienced soldiers who understood that artillery rarely achieved decisive results against well- constructed defenses. When the barrage lifted, all three MG42 teams reopened fire simultaneously.

Their combined cyclic rate creating a wall of lead that seemed physically impossible to penetrate. 3600 rounds per minute from three weapons created a sound unlike anything in warfare. A continuous mechanical scream that drowned out even the explosion of incoming shells. The trapped patrol remained pinned, unable to move forward or backward under the devastating volume of fire.

Corporal Jenkins had been timing the German fire patterns, noting the intervals between sustained bursts and barrel changes. They’re rotating sectors every 90 seconds, he reported to Baines. Lead gun fires for maximum sustained rate until overheating forces a barrel swap. Then the second gun takes over primary suppression while the first reloads and cools down.

The efficiency was remarkable. three guns providing continuous fire coverage through coordinated timing that eliminated gaps in their defensive screen. Bane studied the German positions through his rifle scope, identifying individual crew members and noting their positions relative to their weapons. The MG42 required a crew of three, gunner, assistant gunner, and ammunition bearer.

With the gunner focused entirely on target acquisition and trigger control, while his assistants managed feeding, cooling, and barrel changes, the specialization created devastating efficiency, but also concentrated vulnerability in key personnel. Range to the primary position, Bren asked, already calculating ballistic solutions in his head.

210 m to the bunker, Baines replied. supporting positions at 190 and 230 m, respectively. The distances fell well within the Bren’s effective range, where its superior accuracy could exploit the precision advantages that Bren had engineered into every component. The German confidence was evident in their careless exposure.

Gunners remained visible behind their weapons, trusting in volume of fire to prevent accurate return shots. Their doctrine assumed that enemy machine guns would engage in suppressive duels, area fire against area fire, with victory going to whichever side could sustain higher rates of fire longer. The concept of precision fire from a light machine gun simply didn’t exist in Vermach tactical thinking.

Armstrong lowered his binoculars, his expression grim. Three more patrols have been cancelled. Our supply route is completely interdicted. If we can’t neutralize those positions, the entire sector becomes untenable. He looked at Bren’s small team with barely concealed skepticism. One gun against three, 500 rounds per minute against 3600.

The numbers don’t favor us. Bren’s fingers traced the Bren’s receiver, feeling the precision machining that guaranteed consistent bolt lockup and barrel alignment. Numbers rarely tell the complete story, Major. Sometimes the question isn’t how many shots you can fire, but how many shots you need to fire. He nodded to Baines and Jenkins.

Gentlemen, let’s demonstrate the difference between suppression and elimination. Sergeant Bane settled into his firing position with deliberate calm. The Bren’s bipod legs extended and locked against a low stone wall that provided both stability and concealment. Jenkins positioned himself slightly to the right, spare magazines arranged within easy reach and a fresh barrel lying ready in its protective case.

The weapon’s 22lb weight felt balanced and controllable. Nothing like the crew served heaviness of the German MG42s that required multiple men to relocate effectively. Through the Bren’s rear sight, Baines could see the German gunner in the primary position, adjusting his weapons traverse, completely unaware that he had become the focal point of British attention.

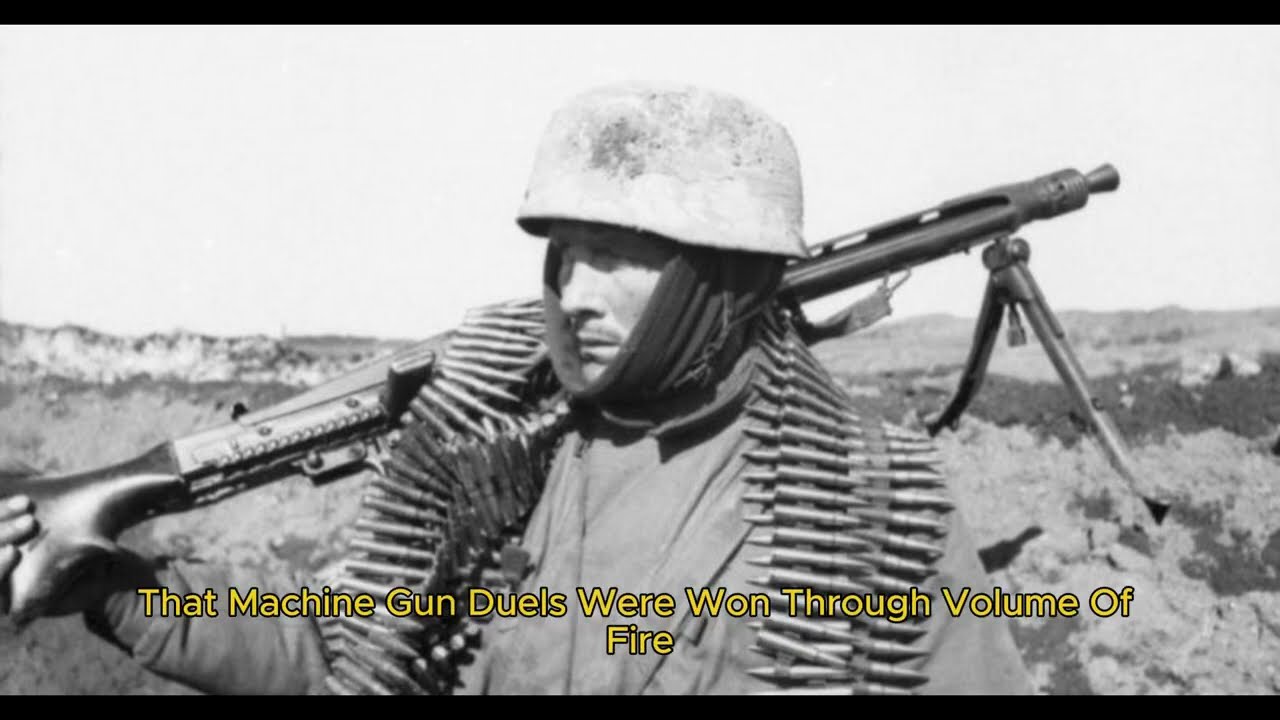

The man’s confidence was evident in his casual posture, no helmet, sleeves rolled up in the Italian heat. His assistant gunner standing fully exposed while feeding an ammunition belt into the weapon. Vermach doctrine had taught them that machine gun duels were won through volume of fire, not precision shooting.

Colonel Bren crouched behind the team, his engineers eye analyzing the tactical geometry with clinical precision. The German positions formed an equilateral triangle with roughly 150 m between each gun. A textbook defensive deployment that maximized mutual support while minimizing vulnerability to area weapons. But the very perfection of their positioning created an opportunity that conventional tactics couldn’t exploit.

Three separate point targets at known ranges, each requiring elimination rather than suppression. The lead MG42 opened fire again, its 1200 round cyclic rate creating the familiar buzzsaw sound that had terrorized Allied infantry across every theater of the war. Tracers arked across the valley in a continuous stream, seeking targets among the scattered rocks where British soldiers remained pinned from the previous engagement.

The German gunner traversed methodically, hosing down potential hiding spots with mechanical thoroughess while his crew prepared for the inevitable barrel change. Baines watched the enemy gunner through his sights, studying the man’s firing pattern and timing. The MG42’s high cyclic rate meant that sustained bursts generated tremendous heat, forcing brief pauses every 30 to 40 rounds to prevent barrel damage.

During those momentary gaps, the gunner’s attention would shift from his targets to his weapon, checking for signs of overheating or ammunition feed problems. It was in those split seconds of distraction that precision fire could achieve what volume never could. The German gun fell silent as the gunner executed a barrel change.

His assistant moving with practiced efficiency to swap the overheated component for a fresh one. The process took 8 seconds. 8 seconds when the primary weapon was completely offline and the gunner’s head was raised above his protective cover. Bane centered his crosshairs on the man’s chest, calculating wind drift and bullet drop across the 210 m range.

Jenkins whispered the range confirmation while keeping his eyes on the supporting German positions. 2110 to primary target. Wind from the left at approximately 5 knots. Supporting guns maintaining overwatch but not actively firing. The tactical intelligence flowed between the team members with the unconscious efficiency of men who had trained together until communication became instinctive.

Bren observed the engagement through his field glasses, noting how the German tactical doctrine created predictable patterns of vulnerability. The MG42’s devastating firepower came at the cost of flexibility. Each weapon required a fixed position, extensive ammunition supply, and multiple crew members to maintain its rate of fire.

The very factors that made it supremely effective in defensive roles also made it predictable to observers who understood its operational limitations. The primary German gun resumed firing, its freshly cooled barrel allowing for sustained bursts that swept across the British positions with methodical precision.

But Baines had identified the pattern now. 30 round bursts followed by brief pauses for barrel cooling with longer intervals every fifth burst for ammunition belt changes. The rhythm was as regular as clockwork driven by the weapon’s mechanical constraints rather than tactical flexibility. When the next pause came, Bane squeezed the Bren’s trigger with surgical precision.

The weapon’s closed bolt firing system meant that the first shot struck exactly where the crosshairs indicated center mass on the German gunner who was raising his head to scan for targets. The 500 round per minute cyclic rate allowed for controlled follow-up shots. Each bullet placed with deliberate accuracy rather than sprayed across a wide area.

The German gunner collapsed backward, his assistant spinning toward the source of incoming fire with shock and confusion clearly visible on his face. The man had never experienced precision fire from a light machine gun. Vermached intelligence insisted that such weapons were area suppression tools, not sniper accurate point systems.

His hesitation cost him his life as Baines placed a second controlled burst into the assistant gunner’s center of mass. The supporting MG42 teams reacted immediately, traversing their weapons toward the British position and opening fire with the overwhelming volume that had dominated battlefields across Europe. 1,200 rounds per minute from each weapon created a devastating crossfire that chewed chunks from the stone wall protecting Baines and his team.

The sound was overwhelming, a mechanical scream that seemed to shake the very ground with its intensity. Jenkins had anticipated the response, already preparing for immediate displacement. Barrel change in 3 seconds, he called to Baines, timing the swap with the precision of a man whose life depended on mechanical efficiency.

The Bren’s quick change barrel system allowed for rapid cooling management without the lengthy process required by belt-fed weapons, maintaining accuracy and reliability under sustained fire conditions. But the German return fire was devastating in its intensity. 2400 rounds per minute from two weapons created a wall of lead that seemed impossible to survive, let alone engage through.

Stone chips flew like shrapnel as bullets impacted around the British position. The sheer volume of fire creating a suppression effect that pinned the team behind inadequate cover. Baines waited for the inevitable pause in German fire, knowing that sustained firing at maximum cyclic rate would force barrel changes on both enemy weapons within minutes.

The MG42’s exceptional rate of fire was also its tactical weakness. No barrel could sustain 1,200 rounds per minute indefinitely without overheating damage. The Germans would have to pause their suppressive fire to maintain their weapons, creating windows of opportunity for precise counter fire. The first German gun fell silent, its barrel glowing red-hot from sustained firing.

The crew worked frantically to execute a barrel change while their comrades maintained suppressive fire. But the 8-second window was exactly what Baines needed. Rising from cover, he placed a controlled three round burst into the second gun position, dropping the gunner and sending his assistant diving for cover.

Jenkins was already moving, carrying the Bren’s spare ammunition and preparing for immediate displacement to a secondary firing position. The German response would be swift and devastating. Mortar fire, artillery support, and possibly infantry assault to eliminate the British team that had suddenly transformed from victims into hunters.

But for the moment, two of three MG42 teams were offline. Their devastating firepower neutralized by precision fire that Vermach doctrine insisted was impossible from light machine guns. The silence that followed was profound, broken only by the distant calls of German voices coordinating their response to this unprecedented threat.

The remaining MG42 crew had repositioned themselves behind a pile of rubble at the far end of the ridge line. Their weapon now angled to provide envelating fire across the entire British sector. Oberloitant Vilhelm Creger emerged from the command bunker, his face grim with the realization that his carefully constructed defensive triangle had been systematically dismantled by a single enemy weapon.

Two of his three gun teams lay silent, their crews eliminated by precision fire that contradicted everything he understood about Allied light machine gun capabilities. Kger’s tactical training had prepared him for conventional machine gun duels, area fire against area fire, with victory determined by sustained volume and crew endurance.

The British were supposed to respond with their own suppressive fire, creating mutual attrition that favored the defenders with superior positions and heavier weapons. Instead, they had employed surgical precision that eliminated his gunners individually while minimizing their own exposure to return fire.

Through field glasses, Creger studied the British position where muzzle flashes had revealed the enemy weapons location. The stone wall provided adequate cover for a small team, but it should have been vulnerable to the concentrated fire of three MG42s operating in coordinated suppression. that a single light machine gun had penetrated his defensive screen and eliminated two of his teams suggested either exceptional marksmanship or technological capabilities that vermached intelligence had failed to identify. Sergeant Baines had already

displaced to a secondary position 50 m south of his original firing point. The Bren’s portable weight allowing for rapid repositioning that heavier weapons could not match. Jenkins followed with spare ammunition and the cooling barrel. Their movement coordinated with the fluid efficiency of soldiers who had learned to work as an integrated weapon system rather than individual components.

The third German position opened fire with desperate intensity. Its crew understanding that they now faced elimination rather than engagement. 1,200 rounds per minute poured across the valley in sweeping arcs, seeking the British team through volume of fire rather than precision targeting. The sound was still devastating.

that mechanical scream that had broken Allied advances across every theater of the war. But without supporting weapons to create overlapping fields of fire, the single MG42 was firing into a tactical void. Colonel Bren observed the German response through his field glasses, noting how desperation had replaced the methodical confidence that characterized Vermach machine gun doctrine.

The remaining crew was expending ammunition at unsustainable rates, their barrel already glowing from sustained firing while they searched for targets that were no longer where they expected them to be. The tactical advantage had shifted completely. Instead of three weapons controlling the battlefield through coordinated fire, a single gun was broadcasting its position while failing to suppress an enemy that had mastered the art of precision engagement.

Kger called for mortar support, knowing that high explosive shells might succeed where machine gun fire had failed. German 81 mm mortars began dropping rounds around the British position, their crews walking the impacts across likely hiding spots with methodical thoroughess. The explosion sent geysers of earth skyward and filled the air with deadly fragments.

But Baines and his team had already anticipated the response and positioned themselves beyond the effective radius of the barrage. The mortar attack revealed the fundamental weakness in German defensive doctrine. It relied on static positions and predetermined fields of fire rather than adaptive tactics that could respond to unexpected threats.

Kger’s guns had been cited to control specific terrain features and approach routes, not to engage mobile targets that employed precision fire from unexpected angles. The very thoroughess of Vermach tactical planning had created blind spots that innovative enemies could exploit. Jenkins spotted movement near the remaining MG42 position as German soldiers attempted to establish a new firing position with better angles on the British team.

The relocation exposed them to observation and fire. Their movement patterns predictable to experienced soldiers who understood how crew served weapons required specific terrain features and setup procedures. Additional targets at 200 m. He whispered to Baines, identifying the assistant gunner and ammunition bearer as they maneuvered their equipment between rocky outcroppings.

Baines adjusted his aim, calculating the lead necessary to engage moving targets at extended range. The Bren’s accuracy advantage was most pronounced against stationary targets, but its stable firing platform and precise sight alignment still provided significant advantages over weapons designed for area suppression rather than point targeting.

The key was patience, waiting for moments when movement patterns created predictable target presentations rather than attempting hasty shots at fleeting opportunities. The German mortar barrage lifted and Creger’s remaining gun crew immediately resumed firing. Their weapon now positioned behind improved cover that limited British observation angles.

But the relocation had cost them their carefully calculated fields of fire, and their new position commanded a narrower sector that left significant dead space where targets could maneuver without exposure. The tactical geometry that had made the original triangle so effective was now working against them.

Baines waited for the inevitable pause in German fire, knowing that the sustained rates required for suppression would force another barrel change within minutes. The MG42’s exceptional cyclic rate had become a liability rather than an advantage. Each burst generated heat that accumulated faster than air cooling could dissipate, creating mechanical constraints that precision weapons could exploit.

When the pause came, he rose from cover and placed a controlled burst into the exposed position where the German gunner was attempting to execute a barrel change. The shot struck with devastating effect, dropping the gunner and sending his assistant scrambling for cover behind the weapon’s shield. But the man’s training betrayed him.

Vermach doctrine emphasized crew continuity over individual survival, and the assistant gunner attempted to take over primary firing duties rather than seeking better cover. His dedication to doctrine cost him his life as Baines placed a second burst center mass, eliminating the last effective gun crew on the ridge line.

Creger found himself commanding a defensive position with no operational weapons. His carefully constructed killing zone reduced to scattered equipment and silent gun positions. The British team that had seemed so inadequate against his overwhelming firepower had systematically eliminated his advantages through precision fire that Vermach tactical thinking insisted was impossible from light infantry weapons.

The sound that had dominated the battlefield for hours, that mechanized scream of rapid fire death, had been replaced by an ominous silence that spoke of tactical revolution. The supply route lay open for the first time in 3 days. British patrols already moving cautiously across terrain that had been an impassible killing zone mere minutes earlier.

Major Armstrong observed the transformation with the wonder of a man witnessing the fundamental assumptions of warfare being rewritten by individual soldiers who understood that precision could triumph over power when applied with sufficient skill and proper equipment. Jenkins checked the Bren’s barrel temperature, noting that controlled fire had generated minimal heat buildup compared to the overheated German weapons that now lay silent across the ridge line.

The aftermath revealed itself in stark, unforgiving detail as British patrols moved cautiously through the German positions that had dominated the Gothic line for three bloody days. Each MG42 imp placement told the same story. Precision fire had found its mark with surgical accuracy, eliminating gun crews with minimal ammunition expenditure, while their devastating weapons lay silent and intact.

The scattered brass around the Bren’s firing positions told a different tale entirely, fewer than 60 rounds expended to neutralize three machine gun teams that had consumed thousands of rounds in their feudal attempts at suppression. Colonel Bren walked among the captured German equipment with the quiet satisfaction of an engineer whose calculations had proven correct under the ultimate test.

The MG42s remained mechanically sound, their barrels still radiating heat from sustained firing, their ammunition belts partially consumed in desperate attempts to maintain volume of fire against an enemy that refused to engage on conventional terms. Each weapon represented the pinnacle of German engineering, 1,200 rounds per minute of devastating firepower that had redefined infantry tactics across every theater of the war.

Yet they had been defeated not by superior firepower, but by superior application of firepower. The Bren’s 500 rounds per minute had proven more than adequate when every shot found its intended target, when controlled bursts eliminated specific threats rather than suppressing general areas. The German doctrine of overwhelming volume had met its antithesis in British precision, and precision had won decisively.

Major Armstrong examined the tactical implications with growing understanding of what they had witnessed. The engagement had lasted less than 20 minutes from first shot to final silence, but those 20 minutes had fundamentally challenged everything Allied forces believed about machine gun warfare. Three German positions that had withstood artillery bombardment, mortar attacks, and repeated infantry assaults had fallen to a single light machine gun operated by two men who understood that accuracy mattered more than volume.

Sergeant Baines cleaned the Bren with methodical care. His experienced hands checking each component for signs of stress or wear from the extended engagement. The weapon had performed flawlessly throughout the action. Its closed bolt system providing the first shot accuracy that made precision fire possible while its quick change barrel allowed for sustained operations without overheating concerns.

The contrast with German equipment was stark. Their overheated barrels and jammed feed mechanisms spoke of weapons pushed beyond their thermal limits in desperate attempts to maintain suppressive fire. Corporal Jenkins tallied the ammunition expenditure with the precision of a quartermaster who understood logistics. 57 rounds fired, three enemy machine gun teams eliminated, multiple crew members neutralized, and a critical supply route reopened.

The efficiency was remarkable compared to conventional suppression tactics that measured success in thousands of rounds expended and enemy positions temporarily silenced rather than permanently eliminated. The Bren had achieved decisive tactical results through surgical application of firepower rather than overwhelming volume.

The human cost became apparent as medical personnel moved through the German positions. Oberloitant Creger had survived the engagement, captured when his command bunker was overrun by advancing British infantry, who no longer faced the devastating crossfire that had pinned them for days. His tactical knowledge would provide valuable intelligence about Vermach defensive doctrine.

But more importantly, his experience represented the collision between traditional military thinking and innovative application of existing technology. In the field hospital, Kger spoke with grudging respect about the engagement that had destroyed his defensive line. Your machine gun, he said to Armstrong through an interpreter, it does not behave as machine gun should behave.

We train to fight weapons that suppress through volume. Your weapon eliminates through precision. This is not how light infantry weapons are supposed to function. Armstrong nodded, understanding that they had witnessed something unprecedented in the evolution of small arms tactics. The Bren LMG had not simply outperformed German weapons.

It had redefined the fundamental role of light machine guns from area suppression tools to precision engagement systems. The implications extended far beyond a single tactical engagement to encompass the entire philosophy of infantry firepower and its application on future battlefields. Colonel Bren found himself surrounded by officers eager to understand how his weapon had achieved such decisive results against supposedly superior German equipment.

The questions came rapidly. barrel life, accuracy specifications, ammunition consumption rates, crew training requirements, and tactical employment doctrine. Each answer revealed another layer of engineering sophistication that had been built into a weapon dismissed by many as inadequately powerful for modern warfare.

The technical demonstration that followed became legendary within British forces as word spread about the engagement at the Gothic line. Bren’s team showed how the weapon’s design philosophy emphasized controllability over raw cyclic rate, precision over suppression, and intelligent application over overwhelming volume. The closed bolt firing system, chromeplated barrel, top-mounted magazine feed, and quick change barrel mechanism all contributed to a weapon system optimized for accuracy rather than area denial.

But the true lesson laid deeper than technical specifications or tactical innovations. Sergeant Baines had demonstrated that individual marksmanship when properly supported by superior equipment design could achieve results that mass firepower could not. His calm precision under fire combined with Jenkins efficient support had created a weapons team that functioned as a single highly effective system rather than separate components operating independently.

The ripple effects of the engagement spread throughout Allied forces as tactical doctrine began adapting to accommodate weapons that bridge the gap between individual rifles and crews served machine guns. The Bren success suggested that light machine guns could serve as precision instruments rather than simple suppression tools, provided their operators understood how to exploit their inherent accuracy advantages over higher volume weapons.

Within weeks, British infantry sections were being reorganized around Bren gun teams that served as the primary source of accurate sustained fire rather than supplementary suppression weapons. The tactical revolution that had begun with Colonel Bren’s engineering philosophy was transforming into operational doctrine that would influence infantry organization for decades to come.

The slow gun had not only proven its worth, it had redefined what light machine guns could accomplish. When precision replaced volume as the governing tactical principle, the Gothic line had fallen not to overwhelming firepower, but to intelligent application of superior technology operated by soldiers who understood that in warfare, as an engineering, effectiveness mattered more than impressive specifications.

Sometimes the quiet solution proved more devastating than the loudest alternative.