May 1945. Across the Soviet Union, from the ruins of Berlin to the ports of Mmansk, from airfields in Poland to depot in the Caucuses, sit hundreds of thousands of Americanbuilt vehicles and aircraft. Studebaker trucks queue by the thousands in maintenance yards. Douglas A20 Havocs rest on air strips alongside Bell P39 Ara Cobras.

These machines sent under the lend lease program that sustained Soviet fighting power since 1941 now face an uncertain future. The war in Europe has ended. But the question of what happens to 427,000 wheeled vehicles and 18,297 aircraft delivered by the United States remains unanswered. Soviet authorities must decide whether to return, purchase, or quietly retain equipment worth billions of dollars.

Meanwhile, American officials demand answers about the largest transfer of military equipment in history. The disposal of lend lease material becomes a diplomatic battle that mirrors the emerging cold war. Whilst the physical fate of these trucks and aircraft tells a story of pragmatic necessity, political calculation and gradual disappearance, the scale of American assistance to the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1945 remains staggering.

Under lend lease, the United States shipped 49,526 trucks to Soviet forces, including 152,000 Studebaker US 62.5 ton cargo trucks, 184,000 General Motors and Dodge Light trucks, and 51,53 Willies and Ford Jeeps. Aircraft deliveries totaled 14,795 aircraft through direct transfer with thousands more provided through other channels.

The Bellp39 Aera Cobra accounted for 4,746 units whilst the Douglas A20 Boston light bomber contributed 2,98 aircraft. Republic P47 Thunderbolts, Curtis P40 Warhawks and North American B-25 Mitchells arrived in substantial numbers. These machines were scattered across hundreds of Soviet military installations by May 1945. Studebaker trucks had become the primary transport for Soviet artillery units and rifle divisions, whilst Americanbuilt fighters equipped entire air regiments.

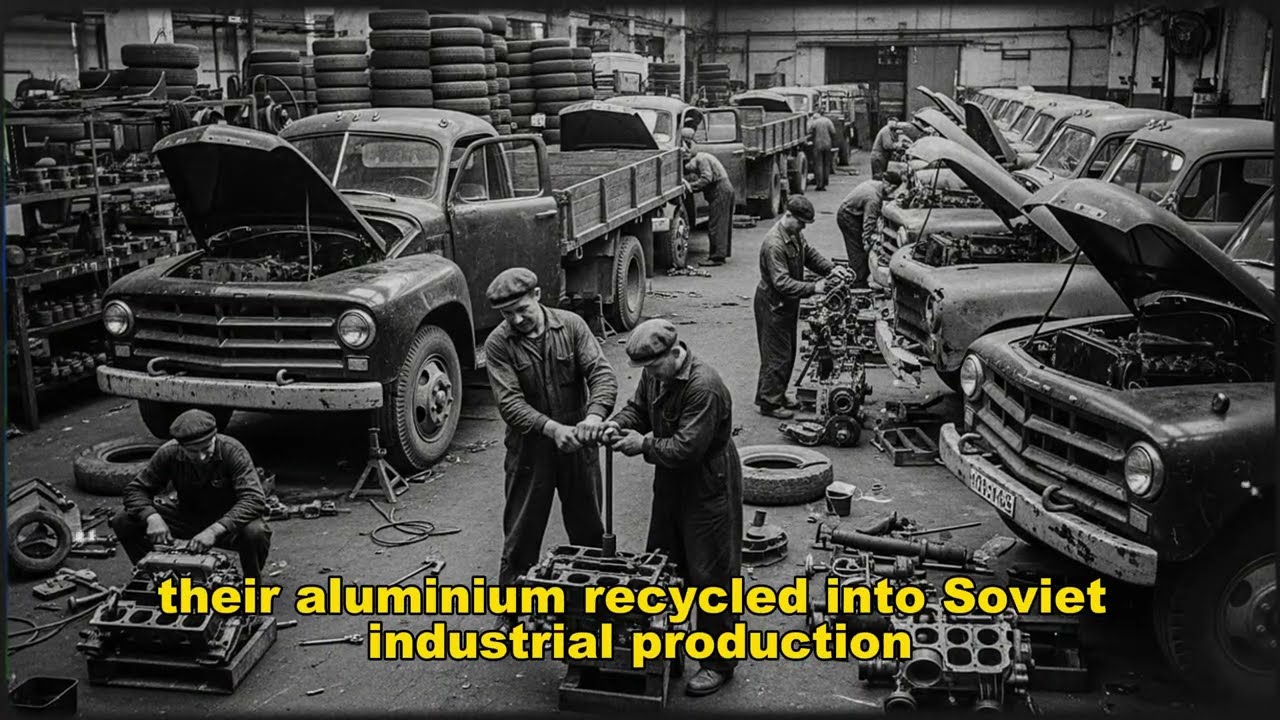

The vehicles and aircraft were wellwn but operational, having survived years of hard use on the Eastern front. Soviet maintenance crews had adapted to American engineering, developing repair procedures and sourcing spare parts through official and improvised channels. Most aircraft showed heavy operational wear with many requiring major overhauls.

The truck fleet exhibited similar patterns of intensive use with some vehicles approaching complete mechanical exhaustion whilst others remained serviceable. This enormous fleet represented not just military hardware but a logistical dependency that Soviet planners viewed with increasing unease as the war concluded.

American officials approached lend lease settlement with clear expectations rooted in the program’s original agreements. The Lend Lease Act of 1941 stipulated that equipment destroyed, lost, or consumed in fighting the common enemy required no payment, but surviving military equipment fell into different categories. Weapon systems, including tanks, artillery, and combat aircraft could be retained without charge if deemed obsolete or impractical to return.

Non-military goods and equipment useful in peace time, however, required either return or purchase. The State Department and War Department created surveys to assess what remained in Soviet hands. Officials estimated that 250,000 to 300,000 trucks survived the war in Soviet service along with perhaps 10,000 to 12,000 aircraft of various conditions.

Washington expected Moscow to purchase civilian useful equipment at depreciated values or return items to American control. The Foreign Economic Administration prepared detailed inventories and established settlement procedures beginning in August 1945. American negotiators proposed that the Soviet Union pay approximately $2.

6 $6 billion for retained lend lease goods with trucks and transport aircraft comprising a significant portion of this valuation. The Americans established warehouses in Germany and Austria where returning equipment could be collected and assessed. Teams prepared to receive, inspect, and catalog returned material throughout 1945 and 1946.

President Truman’s administration viewed lend lease settlement as leverage for broader Soviet cooperation, linking financial resolution to political concessions on European issues. This commercial approach collided with Soviet priorities and perspectives on wartime assistance. Soviet authorities regarded lend lease equipment through a fundamentally different lens.

Stalin and Soviet planners considered American aid compensation for the Soviet Union’s disproportionate sacrifice in defeating Nazi Germany. With 27 million Soviet citizens dead and vast territories devastated, Moscow viewed the trucks and aircraft as partial payment for bearing the war’s heaviest burden. Soviet negotiators argued that most equipment had been destroyed or worn beyond economical repair during combat operations.

Official Soviet responses claimed that only 52,000 trucks remained serviceable by war’s end, a figure American analysts dismissed as deliberately understated by a factor of five. Regarding aircraft, Soviet representatives insisted that combat losses, operational accidents, and normal attrition had reduced Americanbuilt aircraft to negligible numbers.

In reality, Soviet officials had begun systematically redeploying lend lease equipment immediately after Germany’s surrender. Studebaker trucks moved from military units to civilian reconstruction projects, particularly in devastated western regions. Thousands of vehicles were transferred to NKVD border guard units, internal security forces, and civil defense organizations, effectively removing them from military infantries whilst keeping them in state service.

Aircraft faced different calculations. Combat types were rapidly withdrawn from frontline fighter and bomber regiments as Soviet designed aircraft resumed full production. By late 1945, most Bell P39s and Douglas A20 had been relegated to training roles or placed in storage at remote airfields in Central Asia and Siberia.

The Soviet Air Force systematically dismantled American aircraft for spare parts, cannibalizing components to keep reduced numbers flying whilst allowing fuselages to deteriorate. The British position on Soviet lend lease disposal remained largely peripheral but diplomatically significant. Britain had transferred 5,218 aircraft to the Soviet Union under its own programs, mainly huracan fighters and bombers shipped via Arctic convoys to Morman Mans and Archangel.

British supplied vehicles numbered approximately 5,000 trucks and transport vehicles, modest compared to American totals, but still substantial. The Foreign Office coordinated with Washington on settlement expectations whilst maintaining separate accounting for British origin equipment. British officials recognized that Soviet retention of lend lease material undermined the principle that military assistance required eventual settlement.

However, Britain’s own desperate financial position limited diplomatic pressure London could exert. British negotiators observed American settlement discussions closely, understanding that Soviet responses would establish precedents for British claims. The Air Ministry quietly wrote off most huracan fighters as combat losses.

Recognizing that recovery was impractical, British supplied trucks received even less attention with officials acknowledging these vehicles had been absorbed into Soviet transport pools without realistic possibility of return. British diplomats in Moscow reported observing Americanbuilt trucks throughout Soviet cities in 1946 and 1947, often repainted and bearing Soviet markings, but clearly recognizable as studakers or dodges.

These observations supported American claims that Soviet accounts dramatically understated surviving equipment, but Britain’s weakened position prevented forceful independent action. Systematic disposal of lend lease aircraft began accelerating through 1946 and 1947 as Soviet American relations deteriorated. Soviet air force commands received orders to retire American types from operational service and either store or scrap them.

At airfields across the Soviet Union, American aircraft were towed to remote sections and left exposed to weather without maintenance or protection. Airframes deteriorated rapidly in harsh continental climates. Metal corroded, fabric control surfaces rotted, and tires perished. Some aircraft were deliberately stripped of useful components, radios, instruments, engines, propellers before being abandoned.

The aluminium airframes of Bell P30s proved particularly vulnerable with corrosion attacking riveted joints and structural members. By 1948, most stored American aircraft had deteriorated beyond economical restoration. Soviet authorities organized scrapping operations at dozens of airfields with aircraft cut up and melted down for aluminium reclamation.

The Soviet economy’s desperate need for non-ferris metals made scrapping financially attractive. Thousands of aircraft disappeared this way between 1947 and 1950. A few aircraft types received different treatment. The Douglas C47 transport designated Lee 2 in Soviet service proved so useful that Soviet factories had produced licensebuilt copies since 1939.

Lendley C47s continued flying with aeroflot and military transport units well into the 1950s. Similarly, some Bell P39s and P63 King Cobras were retained for specialized training roles until newer Soviet designs completely replaced them. The vast majority, however, ended as scrap metal by 1950, their aluminium recycled into Soviet industrial production.

If you’re finding this exploration of postwar material disposal interesting, consider subscribing for more detailed looks at forgotten historical episodes. The truck fleet followed a different trajectory because wheeled vehicles possessed obvious civilian utility. Soviet planners recognized that Studebaker US6 trucks, Dodge WC vehicles, and Willy’s jeeps could substantially aid reconstruction efforts rather than scrapping or returning these vehicles.

Soviet authorities diverted them systematically into civilian economy sectors. Construction trusts received thousands of trucks for rebuilding devastated cities. Agricultural collectives obtained studakers for hauling harvests and supplies. Forestry operations in Siberia and the Far East acquired rugged American trucks for logging operations.

The NKVD and MVD interior ministry forces absorbed substantial numbers for border patrol and internal security duties. This reallocation removed vehicles from military inventories without destroying their utility. By 1948, Americanbuilt trucks operated throughout the Soviet civilian economy, often badly maintained, but still functional.

Soviet mechanics appreciated the truck’s reliability and load capacity, qualities that Sovietbuilt vehicles often lacked. However, spare parts became increasingly problematic. The United States had supplied enormous quantities of spare parts during the war, tires, batteries, engine components, electrical systems. But these stocks depleted rapidly.

Soviet industry attempted to produce replacement parts for American trucks with mixed results. Some components could be manufactured adequately whilst others proved beyond Soviet industrial capabilities. As vehicles broke down, they became part sources for keeping others operational. By the early 1950s, the surviving truck population had declined substantially through attrition.

Many vehicles sat abandoned in yards and depots, cannibalized for increasingly scarce components. The harsh Soviet climate accelerated deterioration of neglected vehicles. Settlement negotiations between the United States and Soviet Union dragged on for years without resolution. In 1948, American negotiators reduced the requested payment to approximately $1.

3 billion, but Soviet representatives continued disputing valuation methodologies and equipment survival rates. Stalin’s government made token payments totaling approximately $48 million by 1951, a fraction of American claims. The emergence of the Cold War transformed lend lease settlement from a commercial transaction into a symbolic confrontation.

Neither side would compromise in ways that suggested weakness or concession. American officials recognized that recovering or receiving payment for surviving equipment had become impossible. But domestic political considerations prevented writing off Soviet debts. Congress and public opinion viewed Soviet retention of lend lease goods as evidence of communist duplicity.

Successive American administrations maintained official claims whilst privately acknowledging that settlement would never occur. The Soviet position hardened further after Stalin’s death with Krushchev’s government asserting that Soviet wartime sacrifices exceeded any possible American compensation. Formal settlement discussions ceased by 1960 leaving claims officially unresolved.

In 1972 during Dant negotiations resumed under different frameworks resulting in a 1972 agreement where the Soviet Union acknowledged $722 million in lend lease obligations payable over decades. Actual payments remained sporadic and incomplete until the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991. The physical survival of Soviet lend lease equipment became increasingly rare through the 1950s and beyond.

Of approximately 400,000 trucks delivered, perhaps 100,000 survived into the early 1950s, with numbers declining rapidly thereafter. By 1960, Americanbuilt trucks in Soviet service had become uncommon. A few survived in remote regions where replacement vehicles arrived slowly. Far Eastern territories, Central Asian republics, isolated Arctic settlements.

Occasional Studebakers and dodges appeared in Soviet films depicting the 1940s, maintained as period correct props. Museums acquired a handful of examples for military history collections. The Central Museum of Armed Forces in Moscow preserved a Studebaker US6 and a Willies Jeep as representative examples of lend lease assistance.

Similar vehicles appeared in provincial military museums across the Soviet Union. Aircraft survival proved even rarer. By 1960, virtually no lend lease aircraft remained in Soviet service or storage. A few airframes survived as gate guards at air bases or as museum exhibits. The Central Air Force Museum at Monino preserved a Bellp39 Aera Cobra and a Douglas A20 Boston in its collections.

These represented rare survivors from thousands delivered. Soviet museums generally downplayed lend lease contributions during the Cold War, emphasizing Soviet designed equipment and domestic production in great patriotic war narratives. Lend lease exhibits received minimal interpretation or acknowledgement.

After the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, attitudes toward lend lease shifted significantly. Russian historians began reassessing wartime assistance, acknowledging its critical importance to Soviet survival and victory. Museums expanded exhibitions on lend lease equipment, providing more accurate historical context.

Aviation archaeology increased as researchers explored wartime crash sites across former Soviet territories. Several Bell P39 and P63 wrecks were recovered from remote Arctic and Siberian locations, often remarkably preserved in perafrost conditions. Some recovered aircraft underwent restoration in Russia and abroad. The Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum in Washington State acquired and restored a Bellp39Q era Cobra that had served with Soviet forces.

Similar restoration projects occurred in Russia, New Zealand, and Europe. Studebaker trucks proved more resilient at survivors. Dozens emerged from farms, forests, and industrial yards across former Soviet republics where they had languished for decades. Military vehicle collectors and museums sought these survivors eagerly. Restored Studebaker US 6 trucks now appear in Victory Day parades in Russia and participate in historical reenactments.

The Kubinka tank museum near Moscow displays a fully restored Studebaker alongside other lend lease vehicles. Private collectors throughout Russia, Ukraine and Bellarus have restored individual examples to running condition recognizing these vehicles historical significance and mechanical appeal. The legacy of Soviet lend trucks and aircraft extends beyond the hardware itself into questions of Alliance politics and historical memory.

These machines sustained Soviet military operations during the war’s most desperate phases, enabling offensives that might otherwise have stalled. Soviet truck dependence on American vehicles shaped logistical planning and operational capabilities through 1945. After the war, the rapid disposal and reallocation of lend lease equipment reflected Soviet determination to assert independence and eliminate reminders of wartime dependency.

The settlement dispute symbolized broader Soviet American confrontation, transforming commercial obligations into ideological conflicts. For decades, Soviet historioggraphy minimized lend lease contributions, portraying the equipment as supplementary rather than essential. This narrative persisted until the Soviet systems collapse allowed more honest historical assessment.

Today, surviving lend lease vehicles and aircraft in museums serve as tangible evidence of wartime cooperation between ideological enemies, reminders that practical necessity can temporarily bridge even profound political divides. The scarcity of survivors, perhaps two dozen aircraft and several hundred trucks from half a million delivered, illustrates how quickly even numerous and robust equipment can vanish when political will and economic incentives favor disposal over preservation.

The story that began in May 1945 with hundreds of thousands of Americanbuilt trucks and aircraft scattered across Soviet territory concluded with systematic disappearance driven by diplomatic calculation, economic necessity, and political symbolism. Most equipment was neither returned nor formally purchased, but rather absorbed into Soviet state structures and civilian economy before deteriorating through neglect or being scrapped for materials.

The settlement dispute remained unresolved for decades, a minor but persistent irritant in superpower relations. What survives today in museums and collections represents less than onetenth of 1% of what was delivered. precious fragments of a massive material exchange that helped determine the Second World War’s outcome.

If you found this video insightful, watch What Happened to German Tiger tanks after World War II next. It explores how these feared armored vehicles were captured, tested, and ultimately scattered across museums worldwide. Like this video, subscribe, and hit the bell for more. Thanks for watching.