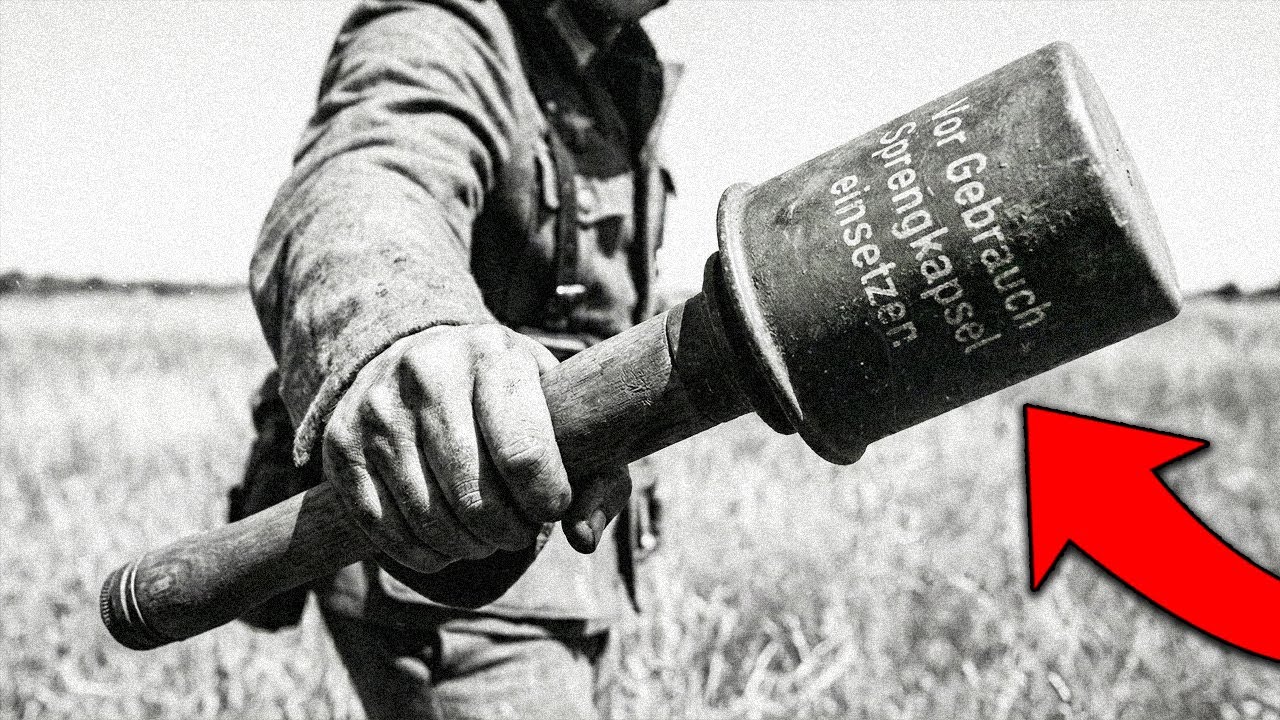

The German war machine was renowned for turning the chaos of war into an orderly system of standards and instructions. However, there was one weapon that broke this rule. A weapon that gave soldiers a unique advantage, but in return took away their chance to remain unnoticed. The still hand granite 24, the legendary slingshot, became the most recognizable grenade in history.

Its long wooden handle was an ingenious engineering solution. It worked like a lever, allowing German grenaders to throw grenades 10 to 15 m farther than any Allied soldier could. However, there was a downside to this physics. The very 36 cm of wooden handle that extended the throw could not be hidden. They protruded from boots, pressed against the ribs, and created a silhouette that enemy snipers could spot instantly.

This is a story of an engineering triumph that turned its owners into priority targets. It is also a story about how the desire to throw further led to the impossibility of hiding. To see how the German army reached this compromise, we must look at its origins. To understand how the German army accepted this compromise, we need to go back to August 1914 when war still seemed like an adventure.

When the German infantry crossed the Belgian border in August 1914, it had only one hand grenade in its arsenal. The Kougalhand granite was a cast iron ball weighing a whole kilogram. It was a cumbersome and heavy weapon intended exclusively for sapper units during the siege of fortresses. An ordinary infantryman could throw such a ball 15 m, 20 at best.

After throwing, he could only pray that he had managed to dive into cover before the shrapnel flew back in the opposite direction. For the maneuver warfare planned by the general staff, this would certainly have been enough. However, by November of that year, the war, which was supposed to end by Christmas, had dug itself into the ground.

In this new reality, a kilogram cast iron ball proved almost useless. The introduction of trenches changed everything. Narrow earthn corridors stretched for hundreds of kilometers from the North Sea to the Swiss border, and opponents could sometimes hear each other breathing through a few meters of mud and planks. Meanwhile, machine guns turned no man’s land into a zone of guaranteed death.

In this new environment, the only way to knock the enemy out of a fortified position was to get close and throw something explosive around a trench bend into a dugout or a machine gun nest. The grenade had gone from being a siege weapon to a tool of daily survival. But at this point, the German army still lacked a grenade suited to this new kind of warfare.

In response, the soldiers began to improvise. In 1915, strange, ugly devices appeared in the trenches, which the British would later call hairbrush grenades. They were tin cans filled with gunpowder, nails, and metal fragments nailed to a wooden handle about 1.5 ft long. The fuse had to be lit by hand, often with a smoldering cigar or pipe.

The design was primitive and dangerously dangerous for the thrower himself. However, these ugly homemade devices flew significantly farther than standard cast iron balls. Among those who observed such improvisations was Hapman Villy Roar. He was a career officer from the Jerger Battalion transferred to the Western Front at the beginning of the war.

The Jagger were a special type of troops. They were used to operating in small groups in wooded areas, making decisions on the spot and relying on their own initiative rather than orders from headquarters. Roar looked at the soldiers making grenades from tin cans and pieces of wood and did not see the chaos of despair. He saw a principle that could be turned into a system.

The handle worked as a lever, extending the thrower’s arm and letting them put more energy into the throw with the same muscle effort. This wasn’t a guess. It was physics, ready to be drawn up and produced. Recognizing this, German engineers took note of the soldiers innovations. In 1915, the chaos of trench improvisations finally reached the offices of the War Department.

The army needed a standardized solution that could be produced in thousands and tens of thousands. The contract for development was awarded to Richard Rinker’s company in the West Failian town of Mendon. A small metalwork firm was about to create one of the most recognizable weapons of the century. The principle borrowed from soldiers homemade devices served as the basis for the design.

A hollow wooden handle about 25 cm long was attached to a cylindrical steel head filled with explosives. Inside the handle was a cord connected to a friction fuse. To activate the grenade, the soldier unscrewed the cap at the end of the handle, pulled out the cord with a porcelain ball at the end, and jerked it sharply.

A rough metal rod was dragged through the ignition compound, striking a shower of sparks. After that, there were 4 and 1/2 seconds left before the explosion. The physics worked flawlessly. The handle extended the thrower’s arm and created additional leverage, increasing the torque when throwing. When the handle was subsequently lengthened from 22 to 36 cm, torque increased by almost 40%.

The grenade rotated around its longitudinal axis in flight, stabilizing its trajectory and improving accuracy. The results spoke for themselves. The British Mills bomb, which later became the standard for the Allied armies, flew 27 m from a standing position. The grenade confidently covered 35 m and in the hands of a trained grenadier, even 40.

A difference of 10 to 15 m may seem insignificant on paper. However, in the confined space of a trench, those meters turned into seconds of advantage. Seconds of advantage often meant the difference between life and death. There was another advantage, less obvious, but no less important. Ordinary egg-shaped or spherical grenades rolled unpredictably when dropped on a slope and sometimes returned to the thrower.

The still hand granite behaved differently. When it fell, it did not roll straight, but tumbled from side to side, staying roughly in place. On a battlefield riddled with craters among trenches and embankments, this property saved lives. The first mass-roduced grenades left the Rinker factory with the Yar mark on the steel head.

Wooden beach handles lay in stacks in the yard waiting to be assembled. What soldiers had made from tin cans and pieces of wood had become a wellestablished industrial product. The 1915 model was the first in a family that would last three decades and sell 75 million copies. However, as the war progressed, the handle showed its downside.

The very length that ensured the throwing range made the grenade bulky and inconvenient to carry. The enemy’s egg-shaped grenades fit compactly into pouches and pockets. The British Mills bomb, the French F1, and later the American MK2 took up minimal space. soldiers could carry four, six, or eight of them without any particular difficulty.

The German grenade did not allow for such luxury. It was tucked behind the belt, behind the bootleg, or threaded through special loops on the chest. No matter how it was carried, it always stuck out. 36 cm of wood that was impossible to hide. This had two consequences, both significant on the battlefield.

First, a soldier with a pair of grenades behind his belt acquired a distinctive, instantly recognizable silhouette. He was visible from a distance, and an experienced enemy immediately understood who he was dealing with. The grenadier was a priority threat and therefore a priority target. Second, the grenade itself was noticeable in flight.

It had a total length of 56 cm, a spinning wooden handle, and a predictable trajectory. It was not a compact ball that was easy to lose sight of against the sky. An attentive enemy could track its flight and react in time. Documents from the British Royal Arsenal record this paradox with characteristic restraint.

The disadvantage of the design was that the size of the grenade made it easy for the enemy to detect and often allowed for a counter throw. It was a fair tradeoff inherent in the design itself. Range in exchange for visibility, an advantage in throwing in exchange for the vulnerability of the thrower. A compromise that was obvious from day one and could not be eliminated by any modifications.

The only question was who would be the first to pay the price. By 1916, as a direct result of these developments, Hopman Villy Roar got what he had been thinking about while watching soldiers with homemade grenades. His own experimental unit cart blanch for tactical experiments and an unlimited supply of new production grenades now rolling off the factory lines by the thousands.

Rar understood what the staff strategists apparently did not. The four-year stalemate of trench warfare could not be broken by massive infantry assaults. Machine guns mowed down the attackers faster than they could cross the no man’s land. Artillery preparations lasting several days only warned the enemy of the strike’s location and turned the battlefield into an impassible mess of craters and mud.

Something fundamentally different was needed. Small groups of specially trained soldiers capable of seeping through weak points in the enemy’s defenses and destroying them from within before the defenders had time to understand what was happening. These men were called assault troops. Each of them was a walking arsenal assembled for one purpose, to break into the trench and clear it before the enemy could react.

A pistol for close combat because a long rifle is only a hindrance in a narrow trench. A sharpened sapper shovel or trench knife for close combat. Sometimes a backpack flamethrower or a submachine gun is used to suppress firing points. However, the main weapon of the assault soldier was the grenade. Bags and loops filled with grenades turned a person into an explosive delivery system.

The assault soldier would tuck a grenade into his belt and feel the wooden handle press against his ribs with every movement. Two grenades in front, two in back, and a few more in a canvas bag slung over his shoulder. He carried more explosives than rifle cartridges, and that made sense. In trench warfare, grenades solved problems that bullets couldn’t.

They got the enemy around corners, smoked them out of their dugouts, and forced machine gunners to duck for those few seconds it took to cover the last few meters. Roar’s tactics were based on speed and surprise. A short artillery barrage concentrated on a narrow section of the front. The assault troops followed immediately behind the barrage, literally stepping on the heels of their own shells.

While the defenders were still recovering from the concussion, the Germans were already in the trenches. Grenades flew around every corner, into every embraasure, into every machine gun nest. An explosion and immediately forward without stopping, without giving the enemy time to gather their strength. The throwing range became critical in the system.

An extra 10 m meant that the assault soldier could cover the firing point while remaining outside the defender’s effective range. An extra 10 m meant that he had time to throw a second grenade while the enemy was still reacting to the first. The Stillahan Granite with its range of 35 m fit perfectly into this tactic.

In February 1916, Roar’s assault battalion led the first wave of the German offensive at Verdun. They broke through the first line of French trenches, carrying grenades instead of rifles and using them with a methodical precision honed by months of training. The losses were heavy, but the method proved its effectiveness.

By the spring of 1918, Roar’s tactics had permeated the entire German army. Operation Michael, the Kaiser’s last great offensive, began with the deployment of half a million soldiers trained to use grenades in confined spaces. During the war, German industry produced 75.5 million of these grenades. That is more than the population of France at the time.

The grenade with a wooden handle became as much a symbol of the German soldier as the steel helmet or hightop boots. However, symbols tend to work both ways. British, French, and American soldiers quickly learn to read silhouettes. A man with distinctive wooden sticks sticking out from his belt and back was not an ordinary infantryman.

He was a grenadier, an assault soldier, someone who in a minute would start throwing explosives into your trench. He had to be killed first and preferably before he got within throwing range. Snipers targeted assault soldiers with their protruding handles. Machine gunners knew who to pick from the advancing chain. The very recognizability that would later turn this weapon into an icon worked as a target on the battlefield.

It was as if each grenadier carried a sign that said, “I am dangerous. Shoot me.” And then the enemy mastered another technique. 5 and 1/2 seconds. That was how long the still hand granite’s delay fuse burned from the moment of activation to the moment of explosion. The delay was calculated to give the thrower time to throw and take cover.

However, 5 and 1/2 seconds turned out to be long enough to react to a flying grenade. 56 cm of spinning wood and metal were clearly visible against the sky. It was not a compact ball that could easily be lost in the air. An attentive and sufficiently coolheaded soldier could track its flight, pick up the fallen grenade, and throw it back.

Not everyone had the nerves for this. Nevertheless, it happened and it happened often enough to make it into reports and dispatches. Roar, by that time already the commander of a full-fledged assault battalion, received reports of casualties from returned grenades. Each such case meant that a weapon designed for attack had worked against the attackers.

The Eastern Front added another problem to this list. At temperatures below 20° below zero, the friction fuse began to malfunction. The soldier would pull the cord, sparks would fly, but the retarder would refuse to ignite. The grenade would turn into a useless piece of wood with a piece of metal at the end.

To solve this problem, a special cold version had to be developed marked cult on the head and equipped with a frostresistant ignition compound. There were other limitations as well. It was a high explosive grenade designed to kill with a shockwave rather than shrapnel. The thin steel casing of the head produced a minimum of shrapnel when it exploded, which was considered an advantage in an attack.

The attacking soldier had no cover and his own grenade was not supposed to kill him. However, in open terrain where a fragmentation grenade retained its lethality at a distance of 100 m, the Tupka lost its effectiveness at a distance of only 15 m from the point of explosion. German engineers tried to compensate for these shortcomings.

In 1942, the splitter ring appeared, a corrugated fragmentation sleeve that could be placed on the head and turn a high explosive grenade into a fragmentation grenade. At the same time, a simplified model 43 was developed, which was cheaper to produce. To combat armored vehicles and fortifications, soldiers tied several heads around a single grenade with a handle, obtaining a bundle with seven times the explosive power.

However, the fundamental paradox remained unsolvable. Removing the handle meant losing range. Leaving the handle meant continuing to expose anyone carrying a grenade. Shortening the fuse delay meant depriving the thrower of time to take cover. Making the body thicker for a fragmentation effect, meant making the grenade heavier and reducing its throwing range.

Every attempt to fix one flaw exacerbated another. The design was what it was, an honest compromise, the terms of which could not be revised. The history of the Stillhand Granite 24 did not end with Germany’s surrender. The concept of a grenade with a handle proved too tempting to die with the army that created it.

And in the following decades, it spread around the world. China began producing copies as early as the 1930s. Artisal workshops stamped out grenades by the thousands, often with a quality far inferior to the German original. During the Battle of Taang in 1938, Chinese soldiers tied bundles of these grenades to themselves and threw themselves under Japanese tanks.

A weapon designed for long range throwing was turned into a tool for suicidal attacks. Japan in turn set up production of its own version designated type 98 in factories in occupied Manuria. The Swedish army adopted the 43rd model grenade with a metal handle instead of a wooden one.

Soviet designers drew on the experience of the German grenade when developing the RGD33. Echoes of the German design were found in Vietnam, Korea, and dozens of local conflicts in the second half of the century. However, after 1945, Western armies abandoned grenades with handles. They abandoned them completely and irrevocably. Compactness won out over range.

The ability to fit six grenades in a pouch instead of two proved more important than a few extra meters of throw. Fragmentation grenades with a safety clip, quick to activate and easy to carry, became the global standard. The American M67, the Soviet RGD5, and the British L109 all fit in the palm of your hand and do not stick out from behind your belt, giving away their owner.

The still hand granite 24 is a thing of the past. A museum exhibit under glass. A rare collector’s item at military antique auctions. A movie prop that instantly tells the viewer the action is taking place on the German side of the front. 75 million were produced over three decades and no army in the world wanted anything like it anymore.

The Stillhand granite was one of the most honest engineering solutions of the 20th century. Honest in the sense that its advantages and disadvantages stemmed from the same source. The handle was the reason for everything. A long throw that gave the assault soldier seconds of advantage.

The protruding silhouette made it a priority target. The visible trajectory allowed the enemy to intercept the grenade and throw it back. It was not a hidden defect that manifested itself too late. It was not a design error that was not corrected in time. It was an open compromise known from day one and accepted with open eyes. Range in exchange for visibility.

Throwing power in exchange for the vulnerability of the thrower. Form followed function. However, that same form created vulnerability. And there was only one way to resolve this contradiction. By abandoning the idea itself, which is what the world ultimately did. Sometimes a good tool is simply a tool with clear limitations.

The still hand granite was just such a tool. It did exactly what it was designed to do, and it paid exactly the price that was built into its design. No more, no less.