An 18-Year-Old German POW Staggered Into a U.S. Camp With a Punctured Lung—What Doctors Discovered Stunned Everyone

MISSOURI, 1944 – The war in Europe was a roaring inferno, consuming cities and lives by the thousands every day. But thousands of miles away, in the quiet, chilly hinterlands of a prisoner-of-war camp in Missouri, a different kind of battle was taking place. It was a silent battle, fought within the ribcage of an 18-year-old boy who had just stepped off a transport truck.

The intake officer recorded his name as “Klaus.” To the casual observer, he was just another enemy soldier—part of the waves of German prisoners arriving on American soil as the Allied forces pushed deeper into Europe. Most of these men were older, exhausted, and frankly, relieved to be out of the killing fields. They stepped off the trucks with a sense of resignation, grateful for the promise of food and a bed.

But Klaus was different.

He didn’t look relieved. He looked like he was holding his breath.

Standing just 5 feet 9 inches tall, he was a spectral figure, leaning heavily against the side of the truck as if the very act of standing required a monumental effort of will. He was pale, his eyes darting nervously, his posture rigid. The intake officer, seasoned by months of processing prisoners, marked it down as fatigue. It was a reasonable assumption. The journey across the Atlantic was grueling, and the conditions in transit were often cramped and uncomfortable.

But fatigue doesn’t make a sound like wet paper tearing inside your chest.

The Medical Exam That Changed Everything

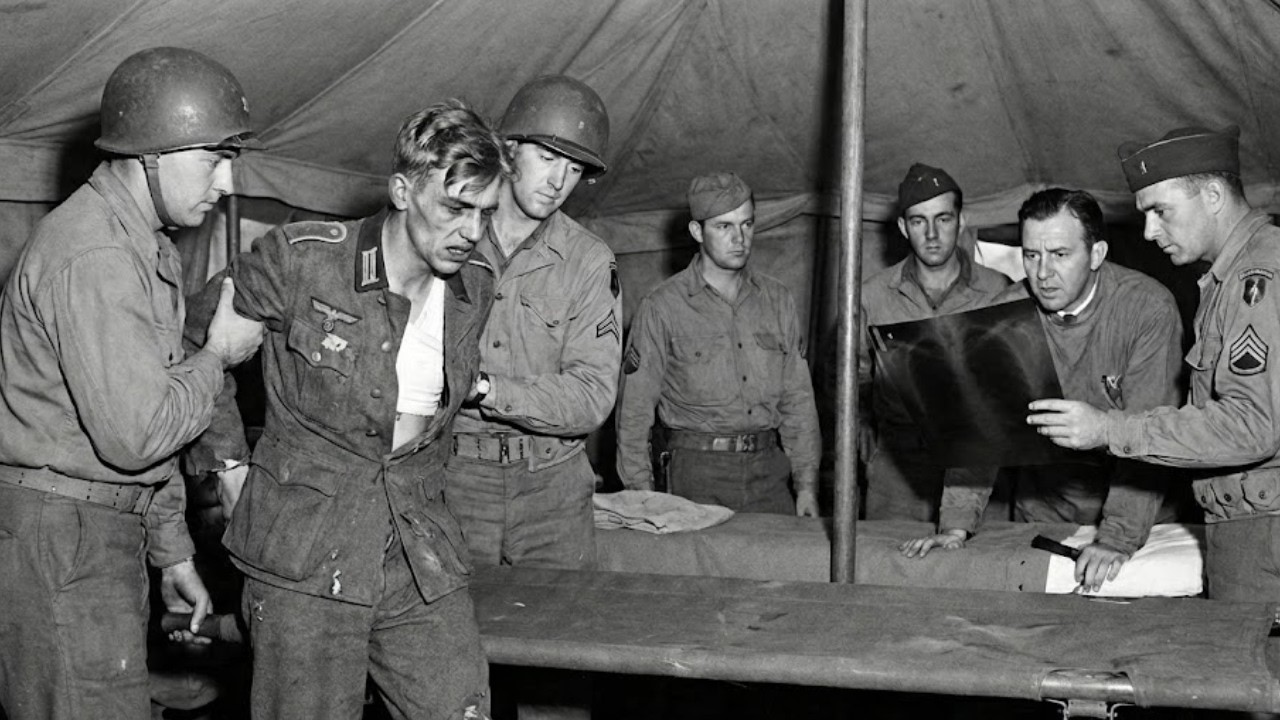

Captain Howard Sullivan was a 36-year-old physician from Pennsylvania, a man who had spent the last six months running the medical processing tent at the camp. He was a methodical man, used to the routine of checking for lice, infectious diseases, and old shrapnel wounds. He had developed a rhythm, a professional detachment necessary for treating the men who, technically, were the enemy.

When Klaus entered the exam tent, that rhythm was shattered.

“Remove your shirt,” Sullivan ordered, his voice echoing in the canvas room.

The boy hesitated. It wasn’t defiance; it was fear. As he slowly peeled back the rough fabric of his uniform, he winced, his hand gripping the edge of the exam table so hard his knuckles turned white. Sullivan’s eyes narrowed. He noticed the breathing immediately. It was short, shallow, and terrified. Every inhale seemed like a calculated risk, a desperate attempt to sip air without expanding the chest too much.

Sullivan stepped forward, his stethoscope dangling from his neck. This was the first red flag. A healthy 18-year-old shouldn’t breathe like a man twice his age in the throes of heart failure.

He placed the cold metal of the stethoscope against the boy’s left lung. Inhale. Exhale. Clear. Normal.

He moved to the right side.

What he heard next would stay with him for the rest of his life. It wasn’t the smooth rush of air filling the alveoli. It was a wet, crackling, tearing sound. It sounded like a sponge being squeezed underwater, a chaotic mix of air and fluid where there should have been only breath.

“Deep breath,” Sullivan commanded, watching the boy’s face.

Klaus tried. He really tried. But halfway through the inhale, his face drained of what little color it had, and he froze, cutting the breath short to stop the agony tearing through his chest.

Sullivan didn’t need an X-ray to know what he was hearing, but the implications were staggering. He switched to basic German, his voice dropping an octave. “When did this happen?”

Klaus stared at the floor, his lips trembling. He remained silent.

“Was it combat?” Sullivan asked.

Silence.

“Transport?”

Klaus looked up, his eyes wide and haunted. “Transport,” he whispered.

One word. That was all Sullivan needed. This boy had been traveling—sitting on trucks, trains, and perhaps even a ship—with a punctured lung for at least three days. Possibly longer. His lung was collapsing, leaking air into his chest cavity with every single breath. The pain would have been blinding. The fact that he was conscious, let alone standing, was a medical impossibility.

A Body Breaking Down

Sullivan immediately ordered an emergency transfer to the camp hospital. “Move him carefully,” he barked at the guards, abandoning his usual calm demeanor. “No jostling. If he falls, he dies.”

As Klaus was carried across the camp on a stretcher, other German POWs watched from behind the chain-link fences. Some of them, veterans of the Eastern Front or the brutal fighting in Normandy, recognized the look on the boy’s face. It was the “thousand-yard stare,” the look of a man who has already accepted his own death.

Inside the hospital—a converted barracks with ten beds and basic surgical equipment—Sullivan began a comprehensive examination. The punctured lung was the immediate threat, a ticking time bomb in the boy’s chest. But as Sullivan peeled back the layers of Klaus’s condition, he found a catastrophe of neglect and abuse.

He checked the boy’s pulse: over 100 beats per minute, fluttering like a trapped bird. He checked the blood pressure: dangerously low. He checked the weight.

This was the second shock. Klaus weighed 112 pounds. For his height and build, he should have been at least 150. He was missing nearly 40 pounds of body mass. He wasn’t just skinny; he was being consumed. His body, starved of nutrients for months, had begun to metabolize its own muscle tissue for energy.

And then there were the scars.

Running horizontally across his ribs, shoulders, and lower back were dozens of thin white lines. Some were old and faded, silver threads of past trauma. Others were pink and angry, fresh wounds that were still trying to knit themselves together.

Sullivan called for the camp interpreter, a German-American corporal who spoke the northern dialect. “Ask him about the scars,” Sullivan said, his voice tight. “These aren’t from shrapnel.”

Klaus sat on the edge of the bed, shivering despite the warmth of the room. He spoke quietly, his voice barely audible. The interpreter leaned in, listening, then turned to Sullivan with a grim expression.

“The scars are from beatings,” the interpreter translated. “Not during combat. During transport. He was held in a detention camp in France for two months before shipping out.”

The story spilled out in fragments. The detention camp had been a nightmare of overcrowding and brutality. Guards, overwhelmed and under-supplied, treated the prisoners like livestock. Discipline was enforced with batons and rifle butts. Food was irregular, a weapon used to control the masses.

“He says he was struck in the chest during a punishment lineup,” the interpreter continued. “He tried to ask for a doctor, but they told him to shut up and keep moving. That’s when the rib cracked. That’s when the lung punctured.”

Klaus had learned a brutal lesson in that camp: Survival means silence. To complain was to invite more pain. To show weakness was to disappear. So, he held his breath. He shallow-breathed his way across the Atlantic Ocean, hiding a mortal injury just to stay alive.

The Procedure

Sullivan knew he had no time to waste. He ordered an X-ray, which confirmed his worst fears. The right lung had collapsed by 30%. The chest cavity was filling with a mixture of blood and air—a condition known as hemopneumothorax. If left untreated, the pressure would continue to build until the lung collapsed completely, and Klaus would suffocate from the inside out.

He had maybe 48 hours.

The procedure required was a thoracentesis. It involved inserting a long, hollow needle through the rib cage and into the pleural space to drain the fluid. It required absolute precision. Go too deep, and you puncture the lung again. Don’t go deep enough, and you miss the fluid.

Klaus was terrified. As Sullivan prepped the needle, the boy’s eyes widened, fixed on the steel instrument. Sullivan explained every step through the interpreter, trying to project a calm he didn’t entirely feel.

“Stay perfectly still,” Sullivan warned.

He injected a local anesthetic between the fifth and sixth ribs. Klaus flinched but didn’t pull away. Thirty seconds later, Sullivan inserted the large needle.

The moment it breached the pleural membrane, the relief was instantaneous—but gruesome. Dark red blood, mixed with clear pleural fluid, began to flow into the collection bottle. Sullivan watched the levels closely. Draining too much fluid too quickly could cause “re-expansion pulmonary edema”—the lung expanding so violently it tears itself apart.

He drained 120 milliliters. Then he stopped.

“Don’t move,” he ordered. “Flat on your back. Six hours. No talking.”

Klaus obeyed. For the first time in days, he took a breath that didn’t feel like a knife twisting in his chest.

The Psychological Wall

The physical recovery was slow but steady. Over the next two weeks, the lung began to re-expand. But the real challenge was just beginning.

Sullivan had designed a “re-feeding plan” to treat Klaus’s severe malnutrition. You cannot simply give a starving man a steak dinner; the sudden influx of calories can cause metabolic shock and death. Sullivan started with small, frequent meals: chicken broth, mashed potatoes, soft bread.

For the first week, Klaus ate voraciously. He gained two pounds. But in the second week, he suddenly stopped.

Sullivan was baffled. The medical charts showed no nausea, no blockage. Yet the trays of food were going untouched.

“Why aren’t you eating?” Sullivan asked through the interpreter.

Klaus looked away, ashamed. “I can’t get fat,” he mumbled.

“What?”

“If I get strong… if I look healthy… they will take me.”

It was a psychological wall built by trauma. In the French detention camp, the healthy prisoners were the first to be picked for brutal labor details. The sick, the weak, the invisible—they were ignored. Klaus had survived by being too broken to be useful. Now, in the safety of the American hospital, his mind was still trapped in that survival logic. He believed that the moment he recovered, he would be punished.

Sullivan sat by his bed for an hour. He didn’t speak as a doctor, but as a human being. He explained that there were no labor camps here. There were no beatings. “Your only job is to get better,” Sullivan insisted. “That is your order.”

It took three days for the message to sink in. Finally, Klaus picked up his spoon.

By the end of the fourth week, he weighed 131 pounds. His cheeks had color. He could stand without dizziness. He was, for all intents and purposes, a new man.

Paradise Behind Wire

When Klaus was finally discharged to the general POW population, he entered a world that felt like a hallucination. The Missouri camp was a “Golden Cage.” The prisoners lived in heated wooden barracks. They had three square meals a day. They had a library.

Klaus was assigned to a farm detail. The work was physical—planting crops, fixing fences—but it was peaceful. The guards were relaxed, often sharing cigarettes with the prisoners. There was no screaming. No fear.

For the next year, Klaus lived a life that was startlingly normal. He spent his evenings in the camp library, teaching himself English with a dictionary. He read books on American history and agriculture. He avoided the hardline Nazi factions that still existed within the camp, the men who whispered about secret weapons and ultimate victory. Klaus knew better. He had seen the reality of the war in his own body.

He was a “pragmatist” now. His ideology was survival.

The Return to Nothing

In April 1945, the war ended. The news rippled through the camp, bringing a mix of cheers and tears. Klaus felt only relief. The killing machine had finally run out of fuel.

But the end of the war brought a new anxiety: repatriation.

In the summer of 1946, Klaus boarded a ship back to Europe. The journey was comfortable, a stark contrast to his arrival, but dread sat heavy in his stomach. He hadn’t heard from his family in Hamburg in over two years.

When the train pulled into Hamburg, Klaus didn’t recognize his own city. The Allied bombing campaigns had turned the metropolis into a moonscape of craters and hollowed-out facades. He walked to his old neighborhood, his heart hammering against his healed ribs.

He found nothing.

His childhood home was gone. Not just damaged—erased. A vacant lot of rubble stood where his bedroom used to be. For the first time since the pain of the punctured lung, Klaus broke down. He stood in the street and wept, mourning not just the house, but the innocence that had been buried under the bricks.

Miraculously, he found his mother and sister weeks later in a displaced persons camp. They had evacuated before the worst of the bombing. They stared at him as if he were a ghost. They had assumed he was dead. The last letter they received was from 1943.

Klaus told them he had been a prisoner in America. He told them the food was good. He told them he worked on a farm.

He never told them about the lung. He never told them about the “wet tearing” sound, the needle, or the starvation. He buried those memories deep, locking them away in the same silent place that had kept him alive in France.

The Legacy of a Survivor

Klaus spent the rest of his life in Hamburg, helping to rebuild the city from the ashes. He worked as a laborer, clearing rubble, laying bricks. He married, had children, and lived a quiet, unremarkable life.

But the war never truly left him. He suffered from “traumatic neurosis”—what we now call PTSD. He would wake up gasping for air, convinced his lung had collapsed again. He couldn’t handle enclosed spaces. The scar tissue in his chest reduced his breathing capacity by 15%, a permanent physical reminder of his journey.

He died in 1992 at the age of 66. His obituary was brief, mentioning only his family and his work. It said nothing of the miracle of his survival.

But Captain Sullivan never forgot. In the medical archives of that Missouri camp, the records of “Klaus” remain—a testament to a time when an American doctor looked at a dying enemy soldier and saw only a boy who needed to breathe. It is a story that reminds us that even in the darkest chapters of history, humanity can still find a way to break through the silence.