Native American Elder Showed Me How To Find Bigfoot – Sasquatch Encounter Story

THE OLD MAN OF THE TRAILHEAD

An Olympic National Forest encounter in six chapters

Chapter 1 — A Forest I Thought I Knew

I never believed in Bigfoot. Not in the serious way, not in the way that changes how you walk through trees after dark. I worked park maintenance in Olympic National Forest—clearing trails, replacing vandalized signs, fixing footbridges after winter floods, hauling out fallen timber before it turned a path into an accident. It wasn’t glamorous work, but it was honest, and it came with something priceless: days spent outside, moving through a world that still felt bigger than people. After three years on those trails I thought I understood the place. I knew which gullies flooded in spring, which ridges caught the worst wind, where elk liked to bed down and where bears showed up when the salmonberries ripened. I thought every sound had an explanation, every track belonged to a known animal, every “weird sighting” from tourists was just a bear standing upright or fog playing tricks.

.

.

.

In summer, Bigfoot stories showed up like mosquitoes. People came in wide-eyed and breathless, swearing they’d seen something tall and hairy cross a service road at dusk. They’d describe howls that didn’t sound like anything on the brochure. They’d bring photos of “giant tracks” that always turned out to be washed-out impressions in mud. My coworkers and I laughed about it over burnt coffee in the ranger station. Olympic had its own Bigfoot industry—museums, burgers, gift shops, keychains—so it was easy to assume all the stories were part of the same harmless machine designed to make tourists spend money and feel a pleasant shiver.

I used to enjoy that shiver. Then I met an old man at a trailhead who didn’t smile like a performer and didn’t talk like a believer trying to convert me. He spoke the way someone speaks when they’re describing weather: calm, certain, and unimpressed by your doubts. And in one week he taught me to see a second forest layered over the first—one made of signs most people step over without noticing, a language written in bent branches and quiet places.

What I saw after that wasn’t a souvenir. It was a presence. And it didn’t care what I believed.

Chapter 2 — The Bench, the Stick, and “The Old Ones”

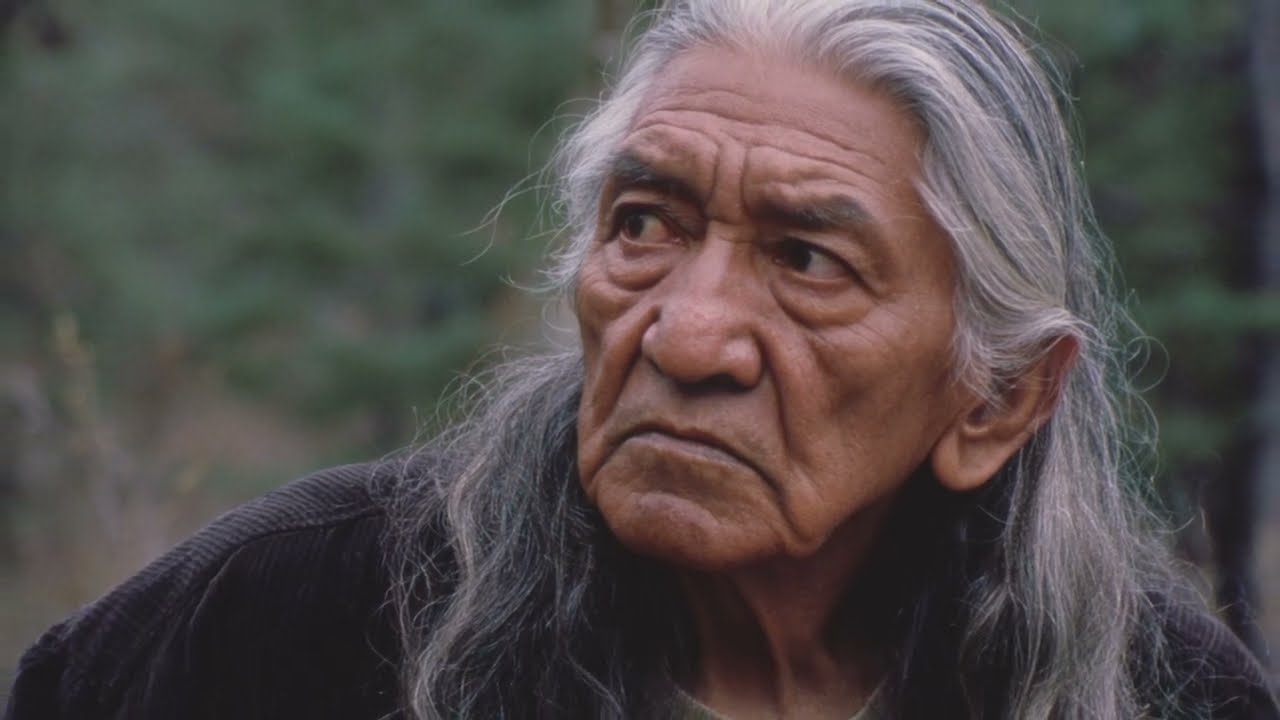

It was a Tuesday afternoon in late September. The parking lot at the trailhead was mostly empty—weekday, cold wind, that gray Pacific Northwest ceiling that can’t decide if it’s rain or just gloom. I was packing tools into my truck when I noticed an elderly Native man sitting on the bench by the trail entrance, facing the trees as if he were watching for something to appear between trunks.

He didn’t look like a hiker. No technical layers, no pack, no water bottle clipped to a strap. He wore worn jeans and a faded flannel, and he held a simple walking stick across his lap—the kind you’d smooth with years of use until it fit your palm like it grew there. What caught my attention wasn’t the clothing, though. It was the stillness. Most people fidget. They check their phones, shift their weight, glance at other cars. He sat like the bench was part of him, spine straight, head slightly angled, eyes focused on the forest with a patient intensity that felt… practiced.

Part of my job is checking on people who might be lost or in trouble, so I walked over and asked if he needed anything. He turned slowly and smiled, and his eyes were sharp—clear and alert in a way that didn’t match the fragile stereotype people carry about age. He said he was fine, just enjoying the quiet. Then, as if we were already in the middle of a conversation, he said the forest was peaceful today and the animals were calm. Something about that phrasing made me pause. It wasn’t mystical, exactly. It was observational, like he was reading a mood.

Then he asked me a question that seemed to come from nowhere: had I ever seen “the old ones” who live here? At first I thought he meant old-growth trees or old trails, and I started to answer in that polite, professional way you answer visitors. But he watched my confusion and corrected it gently. He asked if I’d ever seen the hairy people—the ones that walk like men but aren’t men.

I laughed, not because it was funny, but because discomfort makes you grab for humor. I told him about the tourist sightings, about bears and shadows and imagination. I said we heard these stories all the time. I said people want Bigfoot so badly they turn stumps into monsters.

The smile left his face. Not in anger—more like disappointment, like I’d dismissed something sacred without knowing it. He told me, calmly, that his people had lived in those forests long before the park had a name, and that they had always known about them. He didn’t give me stories for entertainment; he gave me context. He said the hairy people were real, still here, living in remote valleys and deep timber where humans rarely go. Most people didn’t see them because most people didn’t know how to look.

He asked me not to repeat which community he belonged to, because some knowledge was meant to remain within families. I agreed. The request wasn’t dramatic; it was simply firm. That respect—his and mine—became the first step of the lesson.

Before I left, he offered to show me the signs if I was willing to learn. He said most people walk through the forest blind, seeing only what they expect. If I wanted to see what was really there, I’d have to learn to listen the way the land listens.

I surprised myself by saying yes. We agreed to meet at dawn. I drove home unsettled, half certain I’d agreed to a strange errand with a stranger, half aware that something in his certainty had reached under my skepticism and found a hook.

Chapter 3 — Tracking Without Chasing

He was already waiting when I arrived before sunrise. The parking lot was empty except for my truck, and he stood near the trail entrance in the pre-dawn dark like a silhouette cut from the trees. He carried only his stick and a small leather pouch on his belt. I had my work pack—water, first aid, radio, snacks, all the things the job teaches you to carry. He looked at my gear and gave a faint smile that didn’t mock me, exactly, but made me feel like I’d shown up wearing armor to a conversation.

We walked in as the sky lightened to that soft gray that makes everything look older. He moved steadily, stick tapping gently, and every few minutes he would stop completely and just stand—listening, smelling, watching. When he stopped, I stopped, and in those pauses I became aware of how loud my own body was: breath, fabric, boot tread, the restless thump of a mind that wanted an outcome.

Twenty minutes in, he stopped beside a fir and pointed. At first I saw nothing. Then he motioned me closer. Several branches, about seven feet up, were twisted and woven in a way wind doesn’t do. Not snapped. Not bent by snow. Twisted—like hands had taken living wood and turned it into a marker. He showed me a second tree, then a third. Different patterns. Different directions. A language, he said, written in bent wood—trail signs, boundaries, warnings, messages to others who understood the code. Bears break branches. Elk scrape. But those animals don’t tie a sentence into a fir limb and leave it there.

He led me off-trail to a small clearing where heavy logs were stacked into a crude triangular structure. Three thick pieces of Douglas fir, each at least eight feet long, positioned like someone had built a teaching model of a shelter. I tried lifting one end out of curiosity and barely budged it. He didn’t claim to know exactly why those structures existed. He offered possibilities: territorial marker, rain shelter, practice for young ones learning strength and coordination. What mattered wasn’t the conclusion—it was the fact that the arrangement was deliberate. Something had decided to place those logs in that shape and then leave.

Then came the strangest lesson. He told me to close my eyes and breathe. I felt foolish, but I obeyed. At first I smelled only what I expected—pine, damp earth, cold air. Then he guided me twenty feet to the left and told me to smell again.

This time the air had another layer beneath the forest clean: a musky scent, thick and alive, like the concentrated smell of a zoo—but wilder, more primal, less contained. It wasn’t rot. It wasn’t decay. It was an animal presence so strong my instinctive reaction was to recoil. He said quietly: that’s them. Once you learn it, you never forget it.

For a week we met before my shifts. He taught me to find prints in soft mud and read depth, stride, and pressure. He pointed out scratches on bark that started too high for bears and ran downward in long, deep gouges. He taught me to listen for wood knocks—two or three resonant strikes with pauses—sounds too deliberate to be a woodpecker and too deep to be a casual hiking stick. He taught me to notice where the forest went quiet in a way that didn’t match weather or time of day, as if smaller animals had agreed to hold their breath.

Most importantly, he taught me what not to do: don’t chase, don’t corner, don’t follow into thick brush, don’t let curiosity turn into pursuit. If you make them feel trapped, you become a problem they have to solve. If you give them space, they leave. “Respect,” he said, “is not a feeling. It’s behavior.”

On the eighth morning he told me he would show me a place that was still “active.” His tone changed, more serious, like we were stepping closer to something that deserved caution.

Chapter 4 — The Creek That Smelled Like a Hidden Life

We hiked deeper than I’d ever gone for work, down a faint path swallowed by ferns and salal, into old-growth so massive it made my truck feel like a toy. The forest floor was thick with moss, everything damp and quiet, the kind of place where sound feels absorbed rather than echoed. We descended into a narrow valley I didn’t recognize, and at the bottom a creek ran clear and cold over smooth stones, blue-green in a way that looks almost artificial until you remember that some places are simply untouched.

As soon as we got close, I smelled it—the musk, stronger than before, hanging in the air like a presence that didn’t need to be seen to be known. The elder nodded as if confirming what he expected and pointed to the muddy bank.

Footprints. Fresh. Huge—eighteen inches long, maybe more, with five toes clearly impressed and a depth that made my own bootprints look like scratches. The mud had risen around the edges, meaning the tracks were recent, not weathered. I knelt and felt my hands shake, not from cold but from the shock of seeing something so clear that it refused explanation. There were ridges in the impression that looked uncomfortably like skin patterns. It was the sort of detail that makes hoaxes harder to hide and truth harder to swallow.

The tracks led into the creek and emerged on the far bank, disappearing into dense timber. Nearby, tucked in brush, was a crude lean-to structure made from bent saplings and woven branches, just tall enough to provide partial shelter. He pointed out fresh scat too—steaming in the cold air—larger than any bear droppings I’d ever seen, packed with berry seeds and bits of fishbone. Omnivore, he said. Opportunistic. Seasonal. Intelligent enough to eat what the land offers without wasting energy.

Standing there, I felt a strange mixture of awe and discomfort. The evidence wasn’t theatrical. It was ordinary and therefore more terrifying. An animal you can dismiss as a predator. An oddity you can dismiss as a hoax. But a pattern—tracks, shelter, scent, signs—suggests an ongoing presence, a life lived quietly around humans who don’t know how to read the forest.

On the hike back, the elder warned me again: they are usually peaceful, but they are protective. The danger comes when humans act like hunters even when they claim they’re “just curious.” He told me stories passed down from other elders—encounters that turned bad when someone chased, cornered, or tried to force proof.

Then he said something that made my stomach tighten: if I wanted to see one clearly, up close, I would need to observe at night. Not to hunt, not to capture evidence, but to witness. Full moon. No flashlights. No electronics if possible. No radio beeps, no glowing screens, no clicking shutters. Find cover, set up early, stay still, and let the forest decide what to reveal.

The idea felt ridiculous and inevitable at the same time. I took a day off the following week. I told my supervisor it was a family matter. In a way, it was.

Chapter 5 — Moonlight in the Meadow

I hiked into the valley in the afternoon carrying only what I had to: a tarp, a sleeping bag, cold food, water bottles opened at home so there’d be no crack of a seal in the night. No tent—fabric rustles and blocks sightlines. No fire. No phone. No radio. I chose a thicket overlooking a small meadow near the creek, dense evergreen branches giving me shadowed cover while leaving the open grass and water visible through a gap. If anything came to drink, I’d see it in moonlight.

I ate quietly, then tried to sleep as the sun went down, but my mind wouldn’t settle. When I did drift off, it was fitful and thin. I woke to the moon rising huge and orange, then whitening into silver as it climbed. The meadow became a pale dish of light framed by black trees, and the creek’s constant murmur sounded louder at night, like the valley’s heartbeat.

I sat in the thicket for hours. My legs cramped. Mosquitoes found every patch of skin. The urge to shift or scratch became a kind of torture, because stillness isn’t passive—it’s work. Time stretched and warped. I began to wonder if I’d chosen the wrong night, if the elder’s “active” valley was only active on its own schedule.

Around eleven, the forest changed. Not gradually. Instantly. The owls stopped calling. The crickets stopped. The small rustlings in brush ceased. Silence dropped like a curtain, leaving only the creek. The quiet was so complete it felt deliberate, as if the entire ecosystem had agreed to step aside.

Then the smell hit—musky, thick, alive, far stronger than anything I’d caught on earlier mornings. It filled my nose and made my instincts recoil. Something was close. Very close.

I heard heavy footfalls approaching from the forest side of the meadow. Slow steps, measured and confident, branches snapping with crisp cracks that sounded too loud in the silence. Leaves crunched under weight that didn’t bother to be quiet. Whatever was coming wasn’t afraid of anything in that valley.

A massive shape stepped out of the treeline into moonlight.

Chapter 6 — Eye Contact and the Lesson That Remains

It walked upright. Easily eight feet tall—maybe closer to nine—with dark hair covering its body in long shaggy layers. Its shoulders were impossibly broad, arms hanging past its knees, muscles visible beneath the hair when it moved. The proportions were wrong for any human and wrong for any bear: too tall, too long-limbed, too balanced. Its head seemed to sit directly on those shoulders with little visible neck, giving it a slight hunched silhouette.

It crossed the meadow toward the creek with a rolling gait that looked both powerful and efficient, a forward-weighted stride that made its steps feel inevitable. It didn’t scan wildly. It didn’t act nervous. It moved like it belonged there—because it did. I was the intruder, crouched in a thicket like a trespasser on sacred ground.

At the water’s edge it knelt with surprising grace and cupped water with both hands, bringing it to its mouth. The hands looked disturbingly human in structure—five thick fingers, opposable thumbs—built for grip and manipulation, not paws built for tearing. After drinking, it sat on a boulder near the bank and rested, chest rising and falling in slow breaths that fogged in the cold air. Now and then it made low grunting sounds—soft, rhythmic, almost like it was talking to itself or humming in a language made of vibration rather than words.

Then it did something small and strangely intimate: it reached into the creek, lifted a smooth stone, turned it in its hands as if evaluating texture and weight, then tossed it away. It picked up a thick dead branch and snapped it in half with casual ease, as if breaking a pencil. The crack echoed across the meadow. The creature didn’t even seem to strain. The sheer strength in that simple motion made my mouth go dry.

For twenty minutes it just existed—drinking, resting, handling objects with curiosity and control. That ordinariness was what convinced my mind. Legends are dramatic. Real life is mundane. What I watched wasn’t a monster performing; it was a being living.

Then it went still. The change was immediate—every muscle tensing as if a switch flipped. Its head turned slowly, deliberately, directly toward my hiding spot. Not searching. Not guessing. Looking exactly where I was.

Our eyes met across the distance—maybe fifty feet—and my blood turned cold. The eyes caught the moonlight at an angle and flashed amber for a heartbeat, then darkened again. The stare wasn’t animal panic or predator hunger. It was assessment. Conscious attention. As if it were reading me the way I’d been trying to read the forest. I felt exposed in a way I can’t fully describe, like my intentions were louder than my body.

It didn’t charge. It didn’t flee. It held my gaze long enough to make the message clear: I know you’re here. I have known. Then it rose to its full height, let out a single deep huff that vibrated in the air like a low bass note, and turned away. It walked back into the treeline without hurry, every step calm, unbothered, confident. In two strides it was shadow. In three, it was gone—swallowed by the canopy as if the forest had simply decided to close around it.

Minutes later, sound returned. Crickets tested the air again. An owl called in the distance. The valley exhaled. I stayed frozen for an hour, shaking with adrenaline and something that felt uncomfortably like gratitude. At dawn I went to the creek and found what I needed for my own sanity: the boulder still warm where it had sat, massive footprints pressed into mud with crisp detail, the snapped branch pieces lying where they’d fallen, the musky scent lingering faintly in grass. Evidence, yes—but more than that, confirmation that I hadn’t dreamed myself into a story.

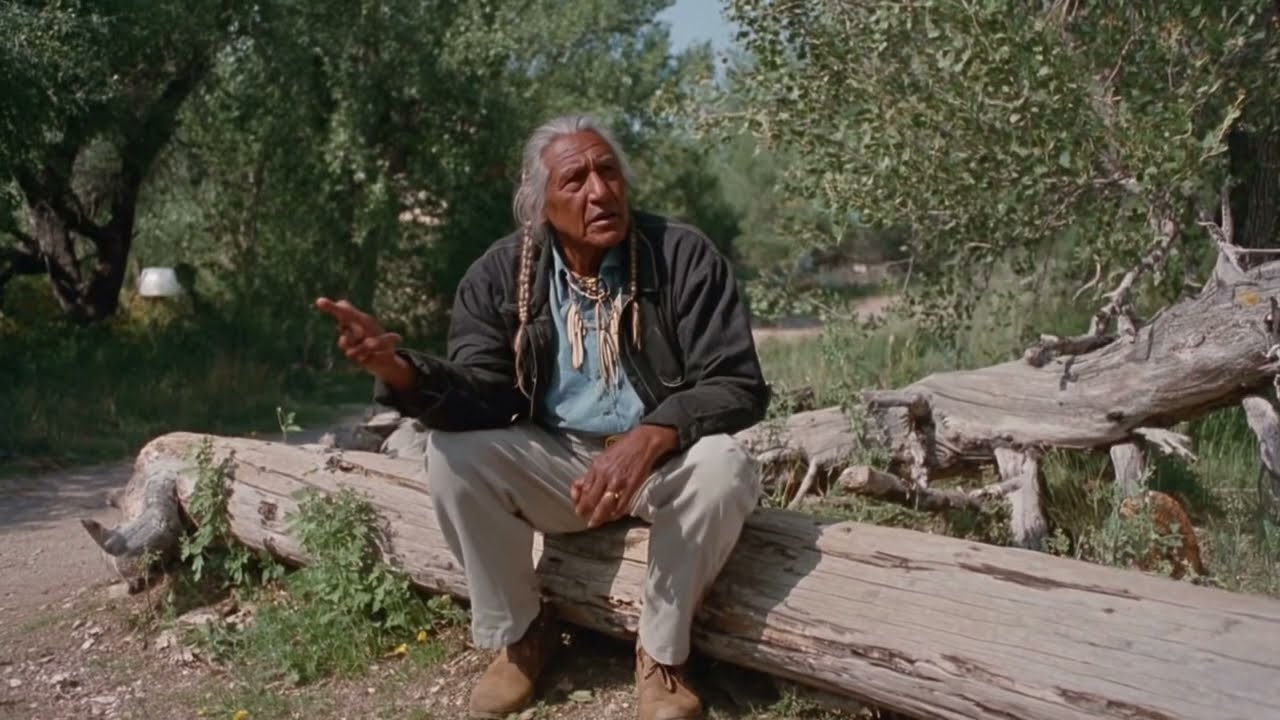

I found the elder at the trailhead later, sitting on the bench like he’d been waiting. I told him everything: the silence, the smell, the way it drank, the way it looked at me. He listened without surprise. When I finished, he said I’d been given a gift—because it could have remained hidden if it wanted to. It chose, for reasons I’ll never understand, to let me witness and then to let me live with that knowledge.

I went back to my job after that, clearing trails and fixing signs, but the forest was no longer a place I “knew.” It was a place I shared. I see twisted branch markers now where I once saw only wind damage. I hear patterns in knocks. Sometimes I catch that musky scent on the breeze and I don’t search for the source. I just keep working and let the unseen keep its distance, because that’s the only respectful arrangement between worlds.

My coworkers still laugh at tourist sightings. I don’t join in anymore. Some knowledge isn’t meant to become a spectacle. Some things are real precisely because they refuse to be proven on demand. And if you ever find yourself in deep wilderness and the forest goes suddenly, unnaturally quiet, the only advice I can offer is the elder’s: don’t chase. Back away. Give space. Be grateful you were noticed—and spared.