German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

The Cellar Where the Rain Wouldn’t Stop (Germany, April 1945)

Chapter 1 — The Eleven in the Dark

Rain fell with the patience of a sentence that would not end. It turned the ruined village of Aken into a slow brown river of mud, sliding through streets where houses had stood only days before. Aboveground, the war still made its noises—distant artillery like doors slamming in another world, the occasional crack of rifle fire, engines growling somewhere beyond the collapsed roofs. But in a bombed-out cellar beneath a broken building, the sounds were muffled, as if the earth itself was trying to forget.

.

.

.

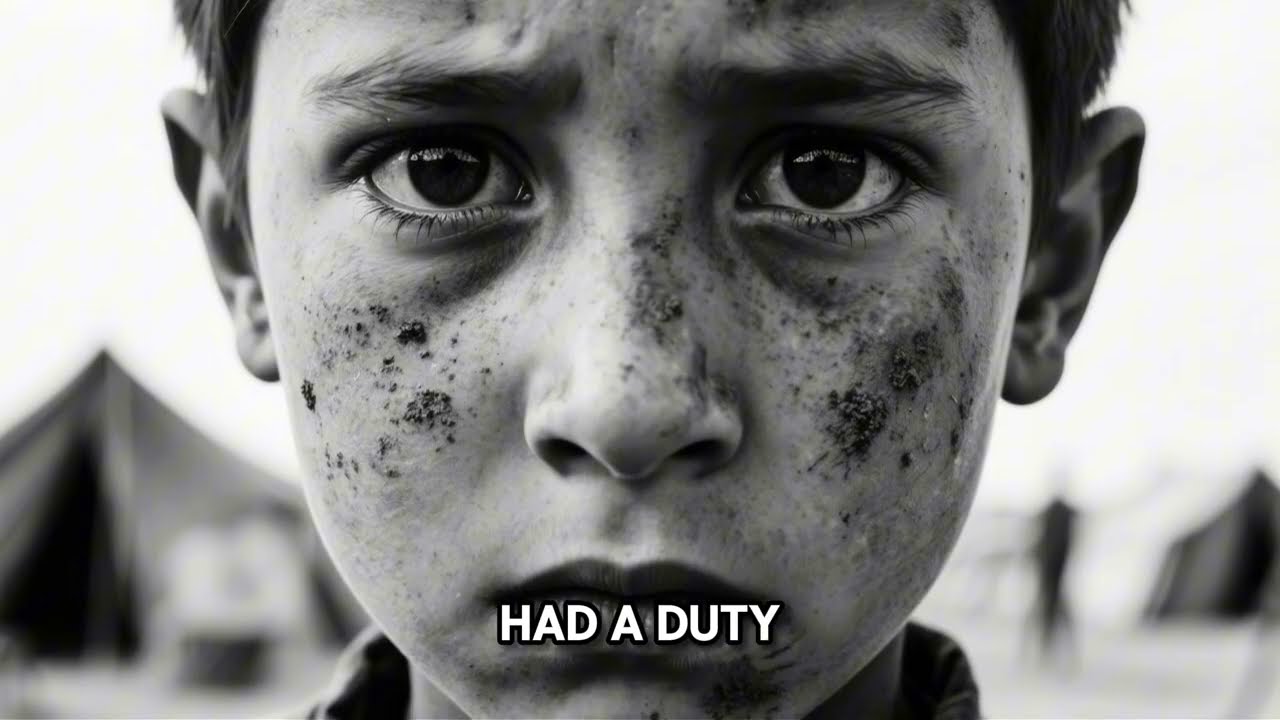

Eleven German boys sat with their backs against damp stone. The youngest was thirteen, the oldest sixteen. Their uniforms—Volkssturm armbands and ill-fitting coats—looked like costumes taken from a storage room and forced into meaning. They had been conscripted three weeks earlier and captured that morning by American infantry pushing through the collapsing front. Their training consisted of shouted instructions, a few hours of drills, and the final, cruel education of fear. The regime had promised them glory. Their bodies knew only hunger and exhaustion.

They had been taught that capture meant summary execution. That Americans shot defenders out of hand. That mercy was a trap used to loosen tongues before death. So when heavy boots descended the cellar stairs, the boys did what children do when they believe the world has become pure danger: they closed their eyes and waited for the end.

The end did not come.

A voice spoke from the doorway above, steady and rough, not triumphant. “Any of you kids speak English?”

The boys opened their eyes, startled by the question itself—by the fact that the voice sounded like a man asking for directions, not a man delivering punishment. In the dim light filtering through the broken ceiling, they could see an American sergeant at the top of the steps. He was tall, broad-shouldered, with three days of stubble and eyes that looked older than his face. He held his rifle the way a man held a tool he’d carried too long.

Silence spread through the cellar until one boy—Peter Keller, fourteen, from outside Stuttgart—lifted his hand slowly. He expected the admission to mark him, to separate him, to make him useful in a way that ended badly. But the sergeant only gestured him forward.

“Come here, son,” he said, and the words, even in English, held something that made them hard to mistrust. “Nobody’s going to hurt you.”

Chapter 2 — The Question Nobody Asked in Germany

Peter stood, his knees trembling so badly he had to brace himself on the wall. Behind him, the other boys watched with a terrible mixture of dread and relief—the kind that makes children feel guilty for being glad they are not the one chosen. Rain dripped through the rubble above and tapped into small pools on the stone floor. Everything smelled of wet dust and old smoke.

The sergeant studied Peter as if trying to place him in a category that made sense. Then he asked, slow enough to be understood, “How old are you?”

“Fourteen, sir,” Peter managed in careful English. His grandmother had lived in London before the Great War and had taught him classroom phrases as if they were small savings against an uncertain future. He had never imagined he would use them in a cellar, at the end of a losing war.

The sergeant shut his eyes for a moment—not in anger, but in a kind of weary restraint, as if he were holding something back. When he opened them, his voice was flat, but the emotion behind it was unmistakable. “Jesus Christ,” he murmured. “They’re sending children now.”

He looked past Peter at the line of faces pressed to the wall. “How old are the others?”

Peter turned, counting quickly, translating what he knew. “Thirteen to sixteen, sir. We are… home defense.”

“Home defense,” the sergeant repeated, as if tasting the absurdity. His jaw tightened. “You should be in school. Not fighting in a war that’s already lost.”

That statement was dangerous in Germany. It was the sort of sentence you learned not to think, much less speak. But Peter had seen enough in three weeks—the shortage of ammunition, the lack of food, the panic in the eyes of men pretending not to be afraid—to know the truth had already slipped free of propaganda. Germany was losing. The only question left was how many children would die before someone admitted it.

Peter swallowed. His mouth was dry. “Sir,” he began, and could not finish. The word he couldn’t say was execute. He couldn’t shape it without making it real.

The sergeant understood anyway. “No,” he said. “We don’t shoot prisoners. Especially not kids forced into uniform by a dying regime.”

Then he turned and called up the stairs in English, voice sharp enough to cut through the rain. “Michaels! Get down here and bring some rations from the supply truck.”

Rations. Food. The cellar seemed to tilt. Peter’s mind struggled to place the order in the world he had been taught. Executions were supposed to be quick. Cruelty was supposed to be certain. Food belonged to victory, not to captivity.

But the sergeant—James Sullivan, though Peter did not yet know his name—looked at them not as trophies, not as villains, but as a problem the war had thrown into his hands and that he intended to solve the only way he knew: by doing the right thing until the situation changed.

Chapter 3 — The Rations That Felt Like a Trick

Private Michaels came down the steps carrying a box of sea rations. He stopped at the bottom, staring at the boys with an expression that mixed anger with something softer he didn’t want to show.

“Jesus, Sarge,” he muttered. “They’re just kids.”

“I know,” Sullivan said. “Give them the food. All of it.”

“But that’s—”

“Now,” Sullivan cut in, not loud, just final. It was the tone of a man who had learned that the battlefield respected clarity. Michaels obeyed. He opened the box and began distributing packets.

The boys took them like they were holding unexploded shells. Some didn’t open them at first. They waited for a smell of poison, for a cruel laugh, for the moment when kindness revealed its true shape. Their suspicion was not stupidity; it was training. Fear had been drilled into them until it became instinct.

Peter translated softly, doing his best to keep his voice steady. “It is safe,” he told them. “He says… we are prisoners now. We will be sent to a camp. The war is almost over.”

One by one, hands fumbled with paper and tin. Inside were crackers, canned meat, chocolate bars—items that, in Germany’s final months, had become nearly mythical. Cigarettes too, though the boys were too young to see them as anything but strange little sticks. The smell of chocolate alone was enough to make a few of them stare as if they were looking at a memory.

The youngest, Klaus, thirteen, bit into a chocolate bar too fast. His empty stomach rebelled. He vomited onto the stone floor, horrified and shaking, convinced he had ruined the only good thing he might ever receive again. Sullivan knelt beside him without hesitation. He offered water from his canteen, spoke gently, and used simple gestures to show him to eat slowly, to let his body adjust. The kindness was more disorienting than the food. It was intimate in a way war rarely allowed—an enemy adult making sure a child didn’t suffer needlessly.

Rain kept dripping. War kept muttering aboveground. But in that cellar, something that had been set hard inside the boys began to loosen. Fear didn’t disappear; it simply stopped being the only thing in the room.

Chapter 4 — Hamburgers on the Rubble

An hour later, when the boys’ trembling had eased into a heavy, bewildered exhaustion, Sullivan made another decision. The rain had thinned. Gray afternoon light leaked through the ruins. Down the street, Sullivan’s unit had established a temporary command post in a partially intact building. A field kitchen was operating there, producing food for American troops who hadn’t slept properly in days.

“Bring them outside,” Sullivan told his squad. “Let’s get them real food.”

The boys emerged from the cellar and blinked in the light. For the first time they saw Aken’s destruction clearly. Buildings were shells. Streets were cratered. The air smelled of wet ash and something worse that the rain could not wash away. This was what they had been told to die for—ruins, smoke, and the hollow pride of being the last ones left.

American soldiers watched them as they passed. Some faces were hard, unwilling to grant the enemy even the softness of pity. Others looked away, as if the sight of boys in uniform forced them to confront a truth too bitter for a soldier’s appetite. A few stared with something like sorrow, because they understood that whatever these children had been told, they were still children.

At the field kitchen, a cook named Rodriguez looked from the boys to Sullivan as if he thought he had misheard reality itself.

“Sarge,” Rodriguez said, “you want me to feed them?”

“They’re prisoners,” Sullivan replied. “They’re kids who haven’t had a decent meal in weeks.”

Rodriguez frowned. “Hamburgers?”

“Hamburgers,” Sullivan said. “Whatever we’ve got. And make it decent.”

Rodriguez hesitated only long enough to decide what kind of man Sullivan was. Then he shrugged, not unkindly. “No problem, Sarge. Hamburgers it is.”

Twenty minutes later, eleven German boys sat on broken bricks and chunks of stone, eating American hamburgers on white bread. There was cheese if they wanted it. Pickles, ketchup, mustard—small luxuries delivered with the casual confidence of a supply chain that still worked. The boys ate slowly now, as if they’d learned that rushing was a form of fear. The food was simple by American standards, but to them it was a feast that didn’t belong in war.

Peter sat beside Sullivan, still half convinced he would wake up back in the cellar. The hamburger tasted better than anything he could remember—not because it was miraculous food, but because it proved he was alive in a world that had promised him only death.

Peter looked at Sullivan and asked the question that was really a doorway. “Why?”

Sullivan chewed thoughtfully, eyes tracking the boys as if counting them, as if ensuring none slipped back into panic.

“Because you’re kids,” he said. “Because this war is already over, even if your leaders won’t admit it. And because treating prisoners right is what separates us from the people who shoved rifles into your hands.”

Peter tried to fit those words into what he had been taught. “The propaganda said Americans were barbaric,” he said quietly.

Sullivan snorted without humor. “I bet it did.” Then, more carefully, as if he refused to sell Peter another neat lie to replace the old one: “We’ve got problems, son. Plenty. But this—” he gestured to the boys eating in the ruins “—this is us trying to be better than the worst versions of ourselves. Doing things right even when it’s easier not to.”

The statement felt like a code. Not a slogan, but a practice. It made Peter uneasy, because it suggested that decency was a choice, not a natural law—and if it was a choice, it could be lost.

Chapter 5 — The Boy Who Wouldn’t Let Go

Not all of the boys softened at once. The oldest, Hans Dier, sixteen, held his hostility like a shield. He had volunteered for the Volkssturm, believing the regime’s promises with the stubborn certainty of someone who needed faith to replace the fear he wouldn’t admit. The hamburger complicated his world, but he resisted the complication. He ate as if it were an insult he could not refuse, jaw tight, eyes narrowed.

An American private watched him and muttered to a friend, “That one still thinks he’s fighting for something. Give him time. Reality has a way of breaking through.”

Hans didn’t understand the words, but he understood the tone. It made him burn with anger. Anger was familiar. Anger matched the stories he knew. Anger kept doubt from spreading.

Yet doubt did spread. It crept in the way rain creeps into ruined walls: slowly, relentlessly, finding every crack. The boys were processed that evening—names recorded, ages verified, photographs taken, numbers assigned. A medic examined them, shaking his head under his breath at every child-sized wrist and hollow face.

“Thirteen,” the medic murmured once, staring at Klaus’s file. “Thirteen years old.”

Sullivan watched it all with a tight, controlled expression. He knew he couldn’t undo what had been done to these boys. No hamburger could restore three stolen weeks. No kind word could put childhood back in place as if it had never been broken. But there was a kind of stubborn American discipline in him: if you couldn’t fix everything, you fixed what you could. You held your standards. You refused to become the thing you fought.

Before the trucks arrived, Sullivan gathered the boys and spoke through Peter. He told them they were going to a camp, that they would have food and shelter and medical care, that the war would end soon, that they would go home if home still existed.

Then he said something that sounded less like an order and more like a charge.

“You were lied to,” Sullivan said, looking at each face in turn. “About the war. About America. About what would happen if you were captured. When you go home, tell the truth.”

Peter translated, voice shaking, because the truth felt heavy in his mouth. The boys listened. Some nodded. Some looked away. Hans glared, but his glare was not as sure as it had been in the cellar.

When Klaus climbed into the truck, he turned back and lifted his hand in a small wave. It was a gesture too small for the history books, but it contained something larger than gratitude. It contained the first fragile idea that mercy could exist in a world built to destroy.

Martinez—an American corporal who had watched Klaus eat slowly—waved back, his face openly human.

“I hope he makes it home,” Martinez said.

Sullivan watched the truck pull away. “If he does,” he replied, “he’ll tell people what happened here. And that will matter.”

Chapter 6 — The Mystery That Followed Him Home

The POW processing center near Brussels swallowed the boys into its vast, orderly machinery—barracks, lists, meal schedules, work details. It was crowded but structured. There was food three times a day, modest but steady. After weeks of hunger, the reliability itself felt unreal. For the first time in months, the boys lived without the immediate expectation of dying before morning.

Klaus cried quietly the first night, grief leaking out now that terror had loosened its grip. “I thought they would shoot us,” he whispered to Peter. “I was certain.”

Peter lay on his bunk and stared into the dark. “I thought the same,” he whispered back. “But they gave us hamburgers instead.”

“Why would the enemy do that?”

Peter searched for words that didn’t feel like another kind of propaganda. “Because they’re not who we were told,” he said. “Because some people follow rules even in war. Even when it would be easier to be cruel.”

Germany surrendered on May 8th. Relief came first, then fear. What waited at home? Who was alive? What would be left of the country that had demanded everything? In the weeks that followed, Peter became an informal translator. His English improved quickly, and the role gave him a strange sense of purpose. He spoke with guards who didn’t treat him like an animal, with clerks who stamped papers as if the world could be repaired by administration, with a sergeant named Williams who had once taught history and spoke to prisoners like future citizens rather than permanent enemies.

“You’re going home eventually,” Williams told Peter one day. “The question is what you build when you get there.”

Peter carried that question like a stone in his pocket. He wrote home as soon as mail became possible, telling his parents not only what had happened, but what it meant: that propaganda worked until it collided with undeniable truth, and that the truth sometimes arrived in small forms—food, water, a refusal to shoot children in a cellar.

When Peter finally returned to Stuttgart, his mother wept and his father held him as if holding him could prevent the past. Peter told his story carefully. Some neighbors called it betrayal. Some listened too closely, as if afraid the truth might change them. His father simply said, with a tired honesty that had outlived ideology, “Germany needs truth more than pride.”

Years later, Peter stood in a lecture hall in Munich and told students about April 1945, about a cellar, about rain, about eleven boys who closed their eyes and waited to die. He told them how the boots came down the stairs and the voice asked, “Any of you kids speak English?” He told them about Sergeant Sullivan, who had looked at children in enemy uniforms and chosen standards over vengeance.

A student once asked him if it sounded too clean, too neatly moral, like a story told to make America look good.

Peter answered without anger. “Propaganda that is true is just called truth,” he said. “And truth does not erase guilt. It only makes rebuilding possible.”

The strange part—the lingering mystery—was not that the boys were fed. The strange part was the way that single decision followed Peter like a shadow he could never fully explain. In the years after the war, as Germany rebuilt itself from rubble, people searched for reasons, for narratives that could bear the weight of what had happened. Some wanted revenge. Some wanted forgetting. Some wanted the comfort of blaming everyone else.

Peter kept returning, quietly, to the cellar where the rain wouldn’t stop and to the hamburger eaten on broken stone. He came to believe that history did not change only through speeches and armies. It also changed through small, stubborn acts—moments when a man with tired eyes refused to become what the war invited him to be.

And that, perhaps, was the real mystery of that day: not why the Americans spared them, but how close the world always is to choosing the opposite, and how much depends on one person deciding, in the middle of ruin, to do something right.