He Fed Mermaids for 40 Years, Then He Learned Why They Fear Humans

I am David Carpenter, 68 years old, and for nearly half a century I have walked the same morning trail down to a cove north of Point Reyes Station, California. Most know me as a retired marine biologist with a fondness for solitary beachwalks. That part is true. What they don’t know is that my real research has never appeared in any journal. It’s a secret I’ve kept so long it’s become part of who I am.

This is the story I was asked to tell, by the beings who trusted me. I write it now because silence has become impossible—and because the world may need to know before it’s too late.

The First Encounter

I grew up as the son of a lighthouse keeper, in a house perched above the Pacific. My father, Robert, kept the beam rotating through storms and fogs, while I learned the rhythms of the sea. My mother left when I was nine, unable to bear the isolation. It was just my father and me, the ocean stretching out forever.

In January 1976, I was sixteen. A winter storm hammered the coast, wind shrieking through the gallery windows. At the height of the storm, I heard something impossible: singing, a melody threading through the roar. I pressed my face to the cold glass, searching the rocks below. Using my father’s binoculars, I caught glimpses of a figure clinging to a rock in a sheltered cove—pale, humanoid, with a tail that shimmered in the beam’s sweep.

I watched, transfixed, as the figure vanished into the surf. I told no one. But the memory stayed, changing how I saw the water, the rocks, the world.

Feeding the Myth

A few weeks later, I began bringing fresh fish to the cove at dawn. At first, I wasn’t sure what I was doing—maybe hoping to see seals or otters. But the figure returned, and soon, two others appeared: a smaller, lighter-colored female and a broad-shouldered male. They waited in the water, watching me. I tossed fish, and they ate, floating in the kelp beds. We never came closer than fifteen feet.

I kept a log, noting times, tides, and species. My father noticed the missing fish, but said nothing. Eventually, I told him everything. He saw them himself one morning, and his only advice was: “You tell no one. You understand me? No one.” We kept the secret together, dividing the feedings between us.

Through trial and error, I learned the rules: come alone, no cameras, no sudden movements, dawn or dusk only, consistency above all. If I missed a feeding, they stayed back, wary. If I brought a friend, they vanished.

Learning Their Ways

As I studied marine biology at UC Santa Cruz, I realized my real education was happening in the cove. I watched their social structure, learned their preferences—rockfish, salmon, lingcod, but never mackerel or sardines. Only fresh fish. I experimented with gestures, and after weeks, the eldest female began responding: raising her hand in imitation, coming forward when I pointed to her.

They learned a basic grammar of interaction. I learned to read their moods, their health. Scars appeared, healed slowly. Sometimes they vanished for weeks, returning with injuries from nets or boats. The ocean was dangerous, and they were survivors.

Over decades, I watched generations grow. The younger female gave birth, brought her infant to the cove. The group expanded, then shrank. The ocean changed around us—warmer water, more nets, more trash. They became more cautious, more distant.

The Lessons of Loss

Some years were harder than others. Injuries from fishing gear, storms, and illness took their toll. The family shrank. Old individuals died; young ones disappeared. I buried one body above the tideline, unseen by anyone else.

They mourned their losses in ways I could only partly understand: vocalizations echoing off the rocks, long periods of silence, new patterns of behavior. I felt my own grief mirrored in theirs.

The Revealing

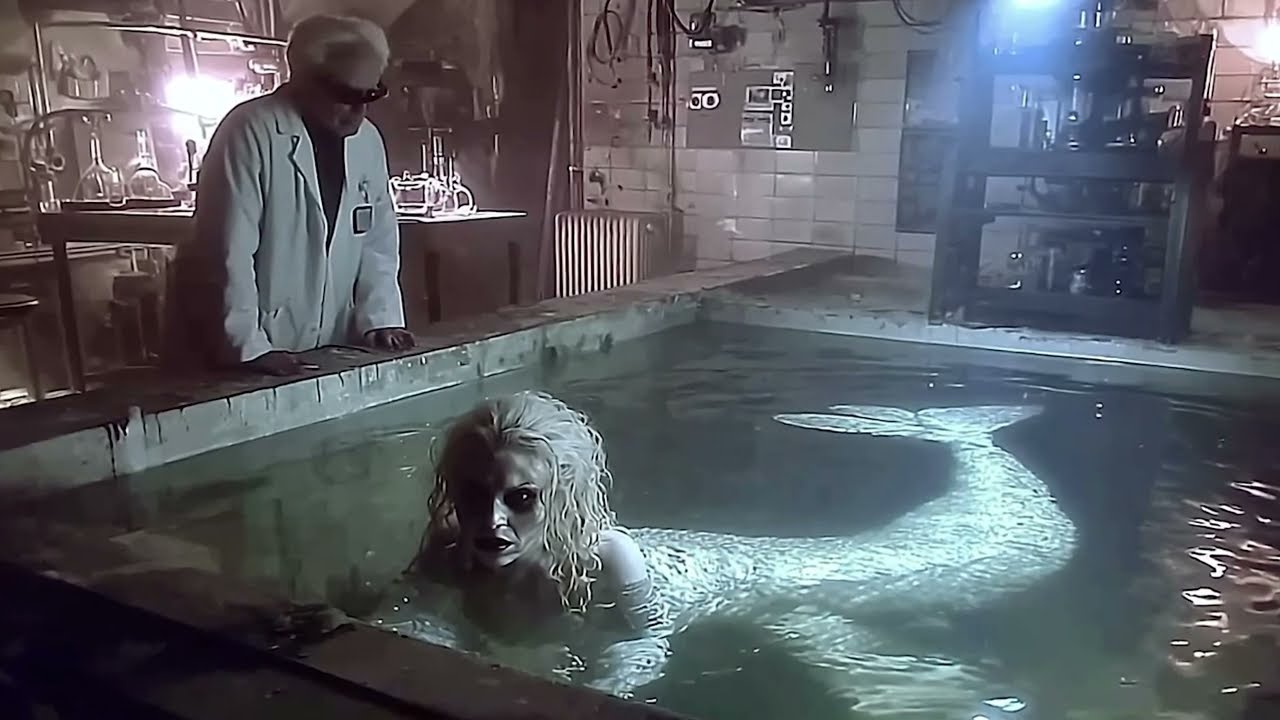

Last spring, everything changed. The eldest female, whom I’d fed for nearly five decades, drew in the sand for the first time. She traced maps—coastlines, population centers, lines connecting humans and her kind. She showed me images of nets, cages, and tanks, of her people hunted, captured, dissected. She drew scenes of retreat, survivors fleeing to deep water, isolated groups hiding from humans.

She pointed at the cove, at herself, at the few remaining companions. “This is what became of us,” she was saying. “We are survivors.”

Her drawings faded with the tide, but the message remained. She was teaching me history—not just biology, but memory, trauma, extinction. She showed me the decline: food sources vanishing, water warming, injuries from nets and propellers. She showed me a skull, the remains of a juvenile lost to illness or injury, the consequences of a population too small to thrive.

The Medical Interlude

Sometimes, she let me help. I cleaned wounds, applied ointment, offered antibiotics. She watched, learned, tried to treat her companions herself. But trust came slowly, and medicine could only do so much.

One young member was injured badly, likely by human technology. I did everything I could—cleaned the wound, bandaged, medicated—but it wasn’t enough. She died, and the mourning that followed was profound, echoing through the cove and through me.

Afterward, the survivors became quieter, thinner, more cautious. The grief was visible in every movement.

The Weight of Witness

The eldest female aged. Her movements slowed, her scars stood out. She had been coming to the cove for longer than I’d known her—perhaps seventy or eighty years. When she dies, only one will remain. When that one dies, this family line will vanish.

She knew this. She began documenting her existence through me, carving a small stone with the image of her kind and mine, separated by a fish—a record of friendship, or at least trust. She gave it to me, and it sits on my desk now, beside decades of handwritten logs.

Her final drawings were about the future: the ocean empty of her kind, darkened by human activity, depleted of fish and kelp. She asked me, “What comes next?”

The Dilemma

I wrestle daily with the question: do I keep their secret, letting them live out their years in peace, or do I speak up, try to find others, seek protection for them? Telling anyone risks exposing them to the same dangers that decimated their ancestors. But silence means their extinction goes unnoticed, their story untold.

One morning, I drew in the sand myself: her, her companion, myself, and other humans. I drew a question mark, seeking permission. She responded with two images—one of the cove, peaceful and protected, surrounded by a circle; the other of the ocean beyond, scattered with question marks. She pointed at these, then at herself and me. “Search. Find.” She was telling me to look for others, but to keep her secret.

The Routine

So I continue the routine. I walk the trail at dawn, bring fresh fish, sit on the rock. I watch the ocean change—warmer, noisier, emptier. I keep logs, photographs (never of them), the carved stone, and this story.

I am 68 years old, carrying a secret that weighs more with each passing day. I am the witness to a vanishing species, trusted by beings who have every reason not to trust humans. I feed them, protect them, document them, and wonder how long it will be before the cove is empty.

The Testimony

If you read this, know that I am breaking my silence in a limited way. I am not revealing the location of the cove, nor enough detail for anyone to find it. I am sharing the truth, hoping someone will search for others, hoping this is not just a story of extinction but a call to action.

The eldest is dying. The last companion will follow. The cove will be empty soon, but I will keep walking the trail, bringing fish to an empty beach, because the memory is all I have left.

The ocean is changing, and so is the world. What do we owe to a species we nearly destroyed? What responsibility do we carry for their survival? What should I do with the knowledge that I may be the last human who ever speaks with them?

I have no answers. Only the routine, the walk, the fish, the weight of the secret, and the hope that somewhere out in the Pacific, others like them still survive.