BREAKING: Helicopter Captures MASSIVE BIGFOOT on Mountain Ridge, Unbelievable Video!

The Ridge That Looked Back

Chapter 1: Blue Sky, Perfect Lift

Sarah Hris had been paragliding for six years—long enough to know the Cascade foothill thermals the way she knew the creases in her own palms, not long enough to lose the electricity of stepping off a ridge and trusting nylon and physics to turn falling into flight. She taught high-school biology in Enumclaw, Washington, which meant her weekdays belonged to fluorescent lights and lab goggles, and her weekends belonged to the sky—quiet, clean, uncomplicated. On this late-September Saturday everything was textbook: high pressure parked over the region, steady southwest winds, unlimited visibility under a blue so sharp it almost stung. She checked forecasts three different ways, cross-referenced the forum chatter, even called the ranger station to confirm there were no access restrictions. Nothing in the data suggested danger. Nothing ever does.

.

.

.

The launch site on the western slope of Stampede Pass sat at 4,800 feet, a fire scar turned natural amphitheater—bare rock and scrub that warmed quickly and kicked off reliable thermals once the sun climbed. Two other pilots were there when Sarah arrived: Derek, mid-fifties, gray beard, the kind of guy who could turn “wing loading ratio” into a sermon; and Travis, younger, a raft guide with a permanent sunburn and a newer wing. They laid out their gliders with the quiet, practical choreography of people who knew the cost of skipping a step. Lines checked. Carabiners locked. Brakes tested. The small talk stayed small.

Derek launched first, orange-and-white canopy inflating cleanly, then he ran and stepped into space and immediately got lifted south. Travis followed, just as smooth. Sarah clipped in last and tapped her helmet mount to confirm the GoPro was recording—habit born from a close call two years earlier when she’d had a partial collapse low to the ground and nothing to review but her own shaky memory. Now she filmed everything, hundreds of hours she never watched, because footage was proof and proof was comfort.

The first step off the ridge was always faith. Her mind understood pressure differentials and angles of attack; her body still remembered what falling meant. Then the wing bit, the lines went taut, and she climbed. The ground slid away. The world opened. Below her, forest rippled dark green, broken by clear-cuts that looked like scars, logging roads like pale stitches. Mount Rainier rose on the southern horizon, glacier-white and indifferent. Up here, everything felt clean: pull right, turn right; pull both brakes, slow down. No politics, no emails, no parent-teacher conferences—just cause and effect.

Around nine, her thermal weakened. The vario’s cheerful beeps turned to a more frequent warning cadence that said sink. She turned northeast toward a ridge she’d flown past dozens of times without really seeing—heavily forested slopes and a bare rocky spine along the crest, too steep and remote for casual hikers. It was one of those backcountry features that existed in endless quantities in Washington: difficult, inconvenient, and therefore mostly ignored. Sarah glided toward it, scanning terrain the way pilots do—landing options, wind tells, obstacles. The ridge itself was too narrow for a safe touchdown, but she spotted a small clearing on the eastern slope, maybe sixty meters across. A backup plan. Just in case.

That’s when she saw the first figure.

Chapter 2: Something Standing Where Nothing Should

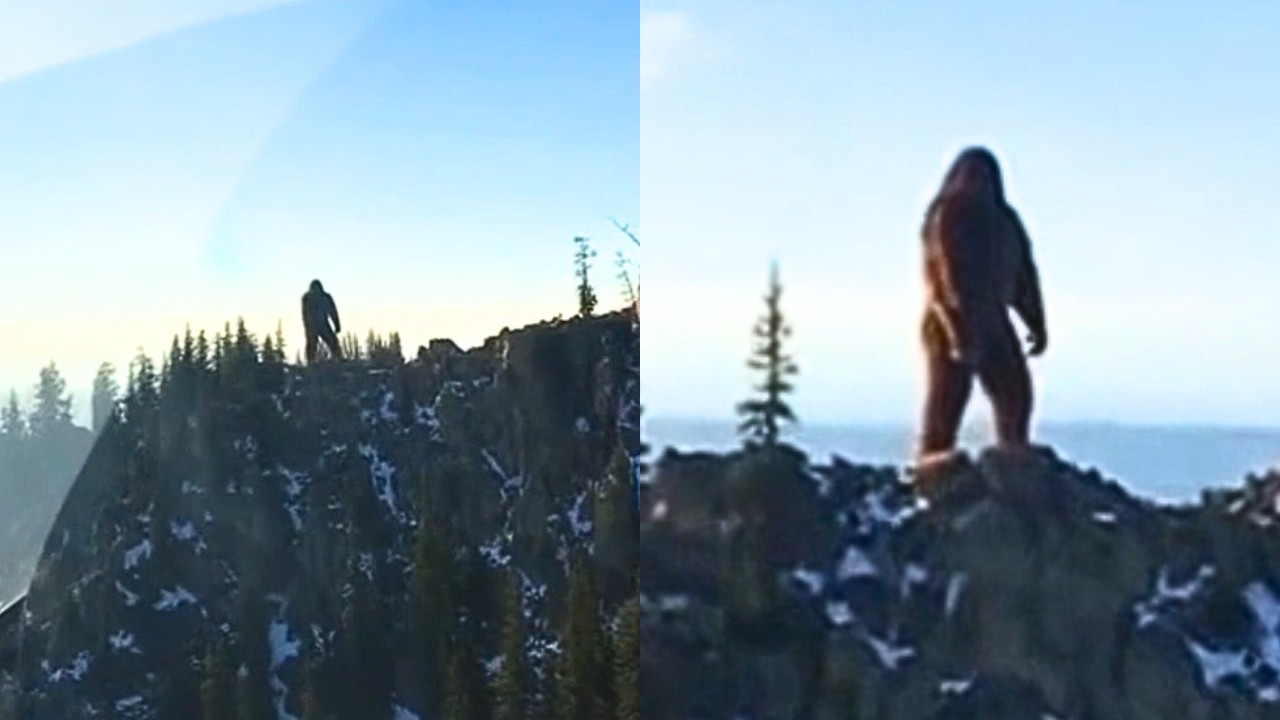

At first her brain refused to label it. It was just a wrongness in the landscape, a shape that didn’t match rock or tree or shadow, a dark upright mark on the southern end of the ridge. She entered a gentle spiral, bleeding altitude to improve her angle, telling herself it had to be a bear on its hind legs or a stump catching the light strangely. But the longer she looked, the more the shape insisted on itself. It was too tall, too broad, too proportioned like a body instead of a trunk. And it wasn’t moving—not foraging, not shifting the way an animal does when it’s unsure. It was standing as if standing was an act of attention.

She was still descending when the second one rose to full height. It had been crouched behind a rock outcrop, hidden from her earlier angle, and when it straightened Sarah felt her hands tighten involuntarily on the brake toggles. This one was larger, its shoulders hunched forward, head seemingly fused to its torso without a visible neck. For a moment, both figures remained perfectly still. Even at more than a mile away, she understood with a cold certainty that they were watching her. Not staring blankly. Tracking. Following her glide across the sky with a focus that made the hairs on her arms lift under her sleeves.

Her rational mind tried to build a scaffold of explanations. Shadows. Perspective. Bears. People in bulky gear. But the closer she drifted, the less the figures resolved into anything reasonable. Arms hung too long. Chests too wide. Posture slightly forward in a way that suggested a center of gravity different from a human’s. The dark texture looked like hair, not fabric. And the stillness—the measured absence of fidgeting—felt like intelligence rather than camouflage.

Sarah fumbled for her radio. “Derek? Travis? Either of you still in the air?” Only static answered. She tried again, voice sharp now, naming her position, describing the ridge, but Derek and Travis had been working thermals south for an hour. Out of range. Possibly already on the ground. She was alone in a wide sky above a ridge that suddenly didn’t feel empty.

Her altitude dropped to five hundred feet above the crest. She realized with irritation and worry that she’d drifted closer than intended—her attention had stolen her discipline. She checked her instruments, corrected her heading, and made a deliberate decision: she would turn her head, put them in the GoPro’s field of view, and capture whatever she could. Proof mattered. Proof would let her breathe later.

At three-quarters of a mile she could see more. The smaller figure’s head looked oddly peaked, cone-shaped in profile, while the larger one’s skull had a pronounced ridge like a gorilla’s—except taller, longer. The bigger one moved its head slightly, tracking her descent. She felt the urge to turn away and return toward familiar terrain, but another part of her—the teacher, the scientist, the woman who trained teenagers to test hypotheses and gather data—insisted she couldn’t just look away. If these things were real, they were the biggest biological story of her life.

She adjusted her course to pass directly over the ridge.

The air was stable now, thermals fading into late morning calm. That meant she was committed to a steady descent. She’d pass above the figures in minutes, maybe one hundred and fifty feet over their heads. Close enough that the camera might catch details the human eye could hold but the mind didn’t want to believe.

At a quarter mile, they moved.

Both turned at once, almost synchronized, stepped backward off the ridge crest, and vanished down the western slope into the trees. One second they were there—dark, enormous, upright—and the next they were swallowed by forest as if the ridge had never held anything living at all. Sarah exhaled a harsh, frustrated sound. She was close and still had nothing she could guarantee would convince anyone. The camera had recorded their disappearance, yes, but the footage would likely be grainy, small, debatable.

She needed to land. She needed to review the video while memory was fresh. She needed to confirm to herself that she wasn’t about to become one of those pilots who told a story everyone politely nodded at and quietly forgot.

Chapter 3: The Landing and the Pixels

The clearing she’d spotted earlier rose toward her faster now. She set her approach, pulled brake, flared late because her mind was still on the ridge, and landed harder than usual—feet hitting, stumbling, wing collapsing behind her in a rush of fabric. The sudden stillness after flight made the world feel loud in its quiet. She stood breathing hard, looking back up at the ridge crest. Nothing. Just rock and scattered trees and a strip of sky that refused to admit it had hosted anything strange.

Packing the wing was muscle memory: lines gathered, fabric folded, everything stuffed into her pack. Sweat dampened her shirt. The sun was higher now, heat pooling in the clearing, and she kept glancing up at the ridge as if it might reassemble itself into figures if she stared long enough. Once the pack was cinched, she sat on a flat rock at the clearing’s edge and pulled out her phone. No signal—expected. She unclipped the microSD from the GoPro and slotted it into her phone with the adapter she kept in her flight kit, hands shaking in a way that irritated her. She wasn’t a jittery person. She was trained. Experienced. Rational. And yet her body was acting like it knew something her mind didn’t want to name.

Two hours and fourteen minutes of footage loaded. She scrubbed forward to the moment she first noticed the ridge. There they were—two dark shapes on rock, upright and wrong. Then the second one stood, movement unmistakably alive. But the resolution was terrible at that distance, the camera’s exposure favoring sky over ground, the figures reduced to a handful of pixels. She zoomed, and the image dissolved into blocky grain. She scrubbed closer, watched them grow slightly larger, then watched them step back and disappear. She replayed it, again and again, adjusting brightness, trying to coax detail out of a camera that had been built to capture wide landscapes, not a hidden truth.

The footage proved something was there. It did not prove what it was.

Sarah saved screenshots anyway. She told herself she’d review on her computer later with better tools, maybe pull more from the raw file. The sensible move was to hike out now. Go home. Calm down. Let daylight and software work. But another impulse rose—a stubborn, insistent need to anchor the pixels with physical reality. If those figures had moved down the western slope, they would have left tracks. Disturbed moss. Broken branches. Something tangible to pair with the video. Something that couldn’t be explained away as a camera artifact.

The ridge was only half a mile. She had water, food, a first-aid kit. Weather was perfect. The terrain was steep but doable. She set a waypoint at the clearing on her GPS, shouldered her pack, and started uphill toward the trees.

Chapter 4: The Smell and the Track

The old-growth forest swallowed her quickly. Douglas fir and western red cedar towered like columns. The understory was open enough for navigation—ferns, moss, rotting logs—and she could see the gray line of the ridge through gaps in branches. The slope demanded attention; her pack shifted and snagged on limbs. About a hundred meters in, the smell hit her like stepping into a different room.

Thick musk. Primate-house funk. Wet dog. Something stale and mammalian that didn’t belong in clean mountain air. It saturated the space so suddenly she stopped and breathed shallowly through her mouth. She turned slowly, searching for a carcass, a bear den, anything that could explain it. Nothing. The smell seemed to come from upslope, from the ridge itself. And the forest had gone quiet. Not peacefully quiet. Unnaturally quiet. No birds. No squirrel chatter. Only her own breathing and the soft scuff of boots on duff.

Every predator-avoidance instinct she had screamed to leave. She tried to bargain with it. Ten more minutes, she told herself. Fifteen at most. Quick look. Evidence. Then gone.

She climbed again, careful, quieter, though the forest never lets you be silent. Ferns brushed her legs. Her pack scraped bark. The smell thickened until she could taste it at the back of her throat. She stepped over a fallen log, worked her pack free from a snag, and on the other side she saw it: a footprint pressed into bare dirt where the ground had been disturbed.

It was enormous—sixteen inches long at least, eight inches wide, sunk deep. Five toe impressions, each tipped with a blunt claw mark. The overall shape was humanoid: heel, arch, ball. But the proportions were wrong. Too wide. Toes too long. The depth implied weight that made her stomach tighten. She photographed it quickly with her phone, placed her boot beside it for scale, took multiple angles, brushed debris away to reveal the full outline. The print was crisp. Recent. It hadn’t softened into the earth yet.

More prints appeared nearby, a track line climbing upslope toward the ridge crest. The stride was absurd—five feet between impressions, too long for a normal human gait on steep terrain. Sarah followed the line until the ground turned rocky and stopped holding detail. Six tracks in total, each one like a signature pressed into the world.

Her heart hammered now, not from exertion but from confirmation. The figures hadn’t been tricks of perspective. They had mass. They had weight. They had walked here. And she was walking into the same space they had chosen.

She pushed through thinning trees and emerged onto the rocky spine of the ridge, sunlight bright enough to make her squint. She recognized the outcrop where one figure had crouched, the open section where the other had stood. From here she could see down to the clearing where she’d landed, and the realization came sharp and sour: from this ridge, the figures could have watched her pack her wing, watch her sit and review the footage, watch her start hiking toward them. They’d known she was coming long before she found the tracks.

She photographed disturbed moss on rock, scraped lichen, shallow depressions that looked like crouching points. She tried to be methodical, scientific, as if discipline could protect her from fear. The camera clicked. Her hands shook. She kept telling herself this was discovery, this was evidence, this was the kind of thing you read about in journals and documentaries.

Then she felt it—a low vibration in her chest, like a sound below the range of clear hearing. It was there and then it was gone, as if something had exhaled a warning and swallowed the rest.

Sarah spun, scanning the ridge. Empty. Trees and rock and sky. She tried speaking, voice small. “Hello. I’m leaving. I’m going now.” The words sounded stupid, but they gave her something to do besides freeze.

She turned downhill and started back toward the clearing, faster than she should have moved on that slope.

Chapter 5: The Dead Screen

Halfway down, the vibration came again—closer now, behind her, sustained for five seconds. She didn’t look back. She forced herself into a fast walk instead of a run, clinging to the idea that running would make her prey. The smell thickened again, as if whatever carried it had shifted position while she climbed. The clearing came into view through the trees, bright and open, and relief pricked at her eyes.

She stumbled into the clearing, spun, and stared at the treeline. Nothing moved. But the smell was everywhere now, heavy and close enough to feel like breath. She grabbed her pack, checked her phone to orient herself toward Forest Road 27—and the phone died in her hand. Not a low-battery shutdown. Just black, sudden, absolute.

She hit the power button. Nothing. Plugged in her battery pack. Nothing. The device was a dead slab. Annoying, she told herself. Bad timing. She still had her dedicated GPS unit clipped to her harness. She pulled it out, pressed power, waited for the startup. The screen flickered once and went dark. She tried again. Nothing. Dead too.

The forest seemed to lean in.

No phone, no GPS, no radio contact. She looked up at the sun, trying to orient by light like it was 1850 instead of 2024. She set off anyway, choosing west by instinct and solar position, telling herself electronics fail sometimes. Telling herself she wasn’t lost. Telling herself she was overreacting.

After twenty minutes, the sun felt wrong. The angle didn’t change the way it should. She turned slowly, searching for landmarks, and the trees gave her nothing. Everything looked the same. The silence returned—no birds, no insect buzz, dead air.

Then the vibration sounded again, longer, and she realized there were two sources: one to her left, one to her right, not quite synchronized. A call-and-response. A surrounding motion. The sound ended and the quiet that followed was worse.

Sarah changed direction and moved downslope toward a creek she could hear, because water meant a line to follow, a path that couldn’t vanish into indecision. She reached the creek, knelt, drank quickly, and a rock the size of a softball arced through the air and splashed twenty feet upstream. She stared at the ripples. Rocks didn’t throw themselves. The message was unmistakable: move.

She started downstream. Rocks came at intervals, landing near her, never hitting—warning shots, herding, correction. She kept moving, boots slipping on wet stones, breath coming in harsh gasps. The creek funneled into a narrow canyon. Walls rose. Light dimmed. Her footsteps echoed. The sound ahead of her came again—downstream this time. One behind. One in front. She was boxed in.

She tried climbing out. The rock turned slick and vertical. She wedged into a narrow chimney and inched upward, pack scraping stone, hands searching for purchase. Fifty feet above the creek she heard movement on the rim—gravel shifting, a heavy presence passing over the slot of sky. A dark shape blotted blue for a heartbeat. Something was up there looking down at her.

Her body made a decision before her mind could argue. She pushed out of the chimney and fell.

She tumbled down the slope, bouncing off rock and brush, pack battering her, and hit the creek hard enough to drive the air from her lungs. She surfaced coughing, eyes stinging, and looked up to see a silhouette on the canyon rim—massive, hunched, watching with a stillness that felt like observation rather than attack.

She splashed downstream as fast as she could, not caring about noise anymore. The canyon opened. She collapsed on a gravel bar, shaking, everything hurting. She checked her gear and felt a cold wave of loss: her helmet was gone. The GoPro with it. The footage—her only clean proof—gone into rock and water and forest.

She lay there trying not to break, trying to breathe through pain and anger, when movement upstream made her sit up.

Two figures stood on the gravel bar sixty yards away.

Chapter 6: The Circle

In late-afternoon light, there was no denying them. The larger one was at least nine feet tall, broad enough to look like a walking wall, arms hanging past its knees, hair so dark it absorbed the day. The smaller one was still enormous, maybe seven and a half feet, more erect, its posture less hunched. They stood still, watching her with patience that felt alien—like time meant something different to them. Sarah forced herself to stand. She backed away slowly downstream. They didn’t move. She backed farther. Still nothing.

Then they began walking, unhurried, their steps eating distance with deceptive ease.

Sarah turned and ran, splashing through the creek, slipping on stones, lungs burning. She rounded a bend and burst into an old clearcut—open ground, low brush, stumps like broken teeth. For a moment she thought openness would save her. It didn’t. The two figures stopped at the treeline and watched. Then a third stepped out across the clearing. Then a fourth. Then a fifth. They arranged themselves in a loose circle, silent, patient, containing her without rushing.

Sarah turned slowly, trying not to hyperventilate. They weren’t charging. They weren’t roaring. They were simply there, like a gate closing. The largest figure—directly in front of her—had a skull shape that caught the fading light, a pronounced ridge, a slightly forward lean that suggested enormous strength held in reserve. Its eyes reflected light in a way that reminded her of animals—tapetum lucidum—yet the focus behind them felt too sharp, too deliberate.

She thought of all the missing-person stories she’d heard, all the old jokes about people vanishing in the mountains, all the comfort humans take in believing the wilderness is empty except for the animals listed on a signboard. She stood in the circle and understood what “apex predator” really meant: not violence, not frenzy, but control.

The largest one lifted an arm and pointed downstream.

Sarah didn’t understand at first. It held the gesture. The other four shifted, stepping aside to open a clear corridor through the circle. The message was simple in the way all true warnings are: Go. Now. Don’t come back.

Sarah walked, then ran, moving through the gap as if the air might harden behind her. She glanced back once and saw them still standing, watching, not following. The pointing arm lowered. The circle remained like a boundary line she had been allowed to cross.

She ran until the clearcut disappeared behind trees, until her legs buckled, until darkness forced her to stop and find shelter under a cedar root mass. She spent the night shivering and sleepless, listening to the low vibrations call and answer through the forest around her. They didn’t approach. They didn’t touch her. They simply existed in the dark with the confidence of beings that owned the terrain.

When dawn came, she followed downhill instinctively until she heard the sound of an engine—human, mechanical, blessed—and found Forest Road 27. She walked south until her truck appeared at the trailhead widening, and she cried with relief as if her body had finally been given permission to react.

Chapter 7: The Cost of Proof

The truck started on the first turn. She drove down toward Enumclaw with hands that wouldn’t stop trembling. She didn’t go home. She went to the police station and told a tired officer she needed to report an encounter in the mountains. The officer listened, skepticism hardening into the familiar shape of a conclusion. “Bear,” she said finally. “Multiple bears. Standing on hind legs. Smell. Vocalizations. It happens, especially if you startled them.”

Sarah tried to explain the ridge. The tracks. The circle. The pointing. The coordinated movements. The electronics dying in her hands like something had reached through the air and pinched them off. The officer offered a charger. After twenty minutes, Sarah’s phone powered on. She navigated to her photos—only to find the files corrupted, unreadable. The officer’s look shifted from skeptical to gently concerned. She suggested rest, hydration, maybe therapy. Dehydration and stress could do strange things to perception.

Sarah left feeling worse than when she arrived. She went to the hospital, got scrapes cleaned, took an X-ray that showed nothing broken, and declined the implied diagnosis that what happened was “in her head.” In her apartment, she sat staring at a dead phone and the absence of evidence. She had been close enough to smell them, close enough to be surrounded, close enough to be spared, and still she had nothing she could put in someone else’s hands.

Over the next weeks she unraveled quietly. She called in sick. Then she resigned. She sold her paragliding gear. She moved to Arizona for open landscapes where nothing could hide in trees because the trees were scarce. She built a life around visibility. And still, she couldn’t fully escape the lesson the ridge had given her: the world is bigger than what we’ve cataloged, and some things are skilled at staying unconfirmed.

Years later, she saw a news article about a missing paraglider in the Cascades—last seen launching near Stampede Pass. Equipment found. No pilot. Search suspended. The familiar geography on the map made her hands go cold. She thought about calling someone, saying something, but what could she offer besides a story and a single blurry screenshot? Silence won by default.

Then an email arrived from a University of Washington anthropologist, Dr. Jennifer Martinez, referencing witness patterns, other pilots, other electronics failures, indigenous stories about “stick people” and “wild men” that sounded less like myth and more like long-term observation. For the first time in a decade, Sarah felt the weight in her chest shift—because she wasn’t alone.

When Dr. Martinez asked her to be interviewed for a documentary project, Sarah stared at the blinking cursor in an empty reply field and understood the real consequence of being spared. Survival isn’t free. Sometimes it creates obligation. You carry the warning. You decide whether to pass it on.

She typed, hands steady for the first time in years, and hit send before fear could rewrite her life back into silence. Outside her Arizona window the mountains were bare and honest. But she knew other mountains weren’t. Other ridges looked back.