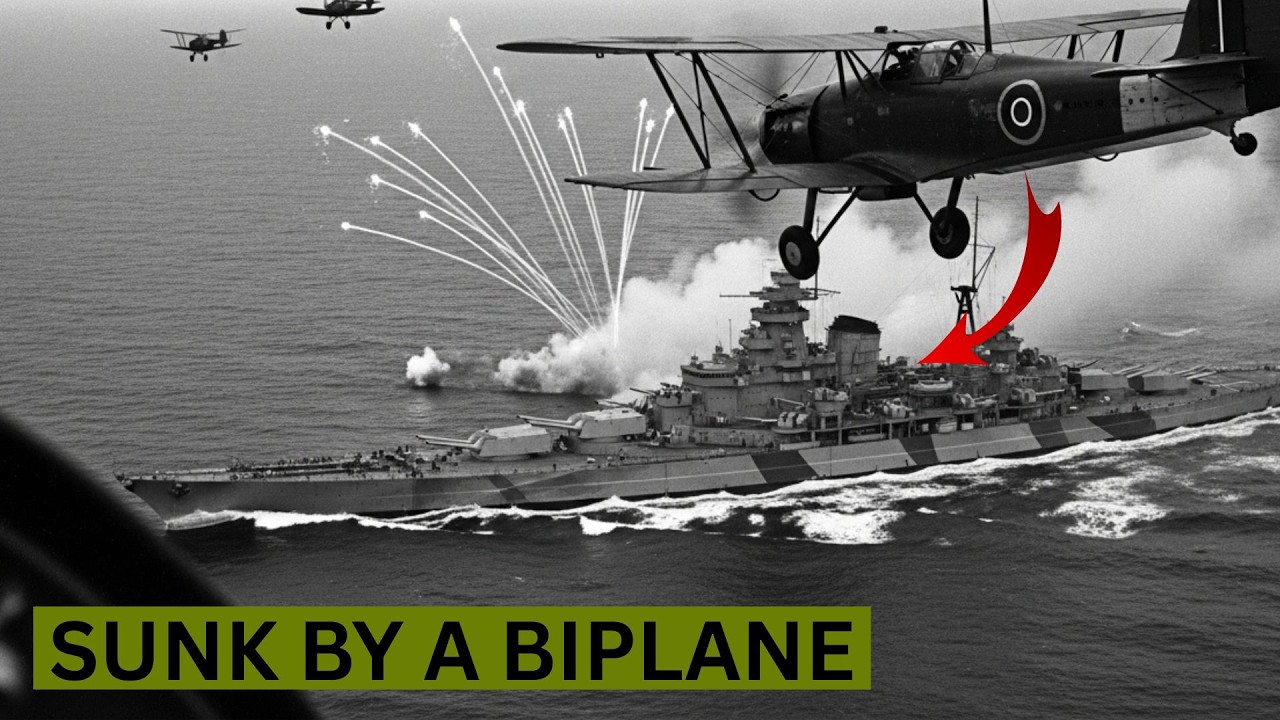

It is 27th May 1941 and the Atlantic Ocean churns beneath a sky the color of wet slate. Aboard HMS Ark Royal somewhere west of Breast. The flight deck crew watches a fairy swordfish biplane lumber into position. The aircraft looks absurd. A relic from the previous war. All canvas and wire struts and an open cockpit where the pilot sits exposed to wind that could freeze a man’s face solid.

The torpedo slung beneath its belly weighs more than a small car. In 90 minutes, this antiquated contraption will the most powerful warship Germany has ever built. The Bismar, a floating fortress of 50,000 tons displacement, armed with guns that can obliterate a target 15 mi distant, will be rendered helpless by technology that belongs in a museum.

The torpedo will strike the battleship stern, jamming her rudders at 12° to port, condemning her to steam in endless circles whilst the Royal Navy closes in for the kill. By dawn on 28th May, the Bismar will rest on the Atlantic floor, taking over 2,000 men with her. The weapon that sealed her fate was not sophisticated. It was not new.

What made it devastating was something the Germans never anticipated. Something so simple that its very crudess became its strength. The British had turned an obsolete aircraft into a delivery system for a weapon the enemy could not defend against, exploiting a vulnerability in German naval architecture that Berlin’s engineers never imagined would matter.

This is the story of how Britain weaponized slow flight and ancient torpedoes to destroy the pride of the criggs marine and why the trick worked again and again turning Germany’s most formidable battleships into floating coffins. The problem Britain faced in 1939 was existential. The Royal Navy had ruled the waves for centuries, but that supremacy rested on a fiction everyone pretended to believe.

British battleships were older, slower, and in many cases outgunned by the vessels Germany and Italy were launching. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, had limited new construction, leaving Britain with a fleet built largely before the Great War, whilst Germany, unconstrained by the treaty until rearmorament began in earnest, could build from scratch with modern metallergy and design principles.

HMS Hood, the pride of the fleet, displaced 47,000 tons and could manage 29 knots. But her armor was fatally thin on the deck, vulnerable to plunging fire. When she faced the Bismar in the Denmark Strait on 24th of May, 1941, a single salvo from the German ship’s 15-in guns penetrated her magazines.

She exploded and sank in less than 3 minutes. of her crew of 1,418 men, three survived. The Royal Navy’s problem was not merely technological, but mathematical. Germany could build faster than Britain could respond. Each new Bismar class battleship represented years of industrial effort, expertise, and resources Britain could not match, while simultaneously maintaining convoy escorts, cruiser patrols, and anti-ubmarine operations across the globe.

Surface engagements between battleships were rare, hugely expensive in fuel and ammunition, and catastrophically risky. Losing a single capital ship meant losing not just the vessel, but hundreds of trained officers and crew who could not be quickly replaced. Britain needed a way to neutralize German battleships without risking her own in gun duels she might not win.

Conventional carrierbased aircraft offered one solution, but in 1939, British carrier aviation lagged behind American and Japanese capabilities. The Ferry Swordfish, which entered service in 1936, had a top speed of approximately 138 mph, making it slower than most fighters from the previous decade. It could not outrun anything.

It could barely outrun a stiff headwind. The solution emerged not from cuttingedge innovation but from stubborn practicality. The ferry aviation company based in Hayes Middle Sex had designed the swordfish as a torpedo bomber reconnaissance aircraft and anti-ubmarine platform. Its open cockpit fabriccovered airframe and fixed undercarriage made it look laughably obsolete even when it was new.

What the designers at Ferry understood and what the fleet air arm would exploit ruthlessly was that the Swordfish flew too slowly to matter to modern air defense systems. German battleships bristled with anti-aircraft guns, rapid fire weapons designed to track and destroy fast-moving targets. The predictive fire control systems calculated where a diving stooker or speeding fighter would be in the next few seconds, adjusting aim accordingly.

A swordfish approaching at 90 knots in a shallow glide fell outside those parameters. It was so slow that gunners overcompensated, firing where they thought the aircraft would be, only to watch tracer rounds arc uselessly ahead of a target that hadn’t arrived yet. The technical specifications of the Swordfish reveal an aircraft built for reliability over performance.

Wingspan measured 45 ft 9 in, fuselage length just over 36 ft. Empty weight came in at roughly 4,700 lb with a maximum takeoff weight around 9,200 lb when carrying a torpedo. The power plant was a Bristol Pegasus radial engine producing 690 horsepower, enough to haul the aircraft and its weapon into the air, but hardly enough for dramatic maneuvers.

Maximum range with a torpedo load was approximately 546 mi, requiring carriers to close within striking distance of their targets. The crew consisted of three men, pilot, observer, and telegraphist/air gunner, all exposed to the elements. In Arctic conditions, pilots reported ice forming on their goggles mid-flight.

Production numbers remain somewhat uncertain due to wartime recordkeeping, but estimates suggest approximately 2,400 swordfish were manufactured between 1936 and 1944. Built at Fair’s facility in Hayes and later at Blackburn Aircrafts factory in Sherburn in Elmer, Yorkshire, the torpedo itself deserves attention. The standard fleet airarm aerial torpedo was the Mark 12, an 18-in diameter weapon approximately 17 ft long, weighing around 1,600 lb.

The warhead contained 388 lb of torpex, an explosive roughly 50% more powerful than TNT by weight. dropped from low altitude, ideally between 50 and 100 ft. The torpedo entered the water, stabilized, and ran on a preset depth and course toward its target. The challenge lay in getting close enough to release it. Torpedo attacks required aircraft to fly straight and level at predictable altitude for the final approach, making them hideously vulnerable.

The Swordfish’s solution was to approach so slowly at such low altitude that defending gunners simply could not adjust their aim fast enough. The operational deployment of Swordfish against German capital ships reads like a case study in exploiting enemy assumptions. The first major success came at Toronto on the night of November 11th, 1940, where 21 swordfish from HMS Illustrious attacked the Italian fleet at anchor.

They sank the battleship Conte Davour and severely damaged Letorio and Kaio Dilio, effectively crippling Italy’s surface fleet for months. The attack demonstrated that obsolete biplanes could achieve what battleship guns could not. Germany paid attention but drew the wrong conclusions, believing faster, more modern aircraft posed the real threat.

The Bismar operation revealed the flaw in that reasoning. After sinking HMS Hood, Bismar and her consort, Prince Yugen made for occupied France, pursued by much of the home fleet. On the evening of 26th May, swordfish from Ark Royal located the battleship steaming south. 15 aircraft launched into deteriorating weather, flying through rain squalls and clouds so thick that navigation became guesswork.

The attack commenced at approximately 20047 hours. Bismar’s anti-aircraft batteries opened up, filling the sky with flack, but the Swordfish bored in at wavetop height, slow enough that the battleship’s fire control systems struggled to track them. One torpedo, possibly dropped by Lieutenant Commander John Moffett’s aircraft, struck Bismar’s stern.

The explosion jammed both rudders and damaged the steering gear beyond repair. Bismar could no longer maneuver. She could only steam in wide circles whilst destroyers harassed her through the night and battleships closed the distance. By morning, HMS King George V and HMS Rodney pounded her into scrap metal. The psychological impact on the creeks marine was profound.

Germany’s most modern battleship designed to be invulnerable had been crippled by fabriccovered bipplanes. The official German naval history downplayed the torpedo hit, attributing the loss to the subsequent battleship engagement, but the facts remain undeniable. Without that jammed rudder, Bismar would have reached air cover from occupied France.

If you are finding this interesting, a quick subscribe helps more than you know. The comparative analysis between British, German, and American approaches to torpedo aviation reveals starkly different philosophies. Germany never developed an effective carrierbased torpedo bomber partly because the Graph Zeppelin, Germany’s only aircraft carrier, never entered service.

The Luftvafer focused on dive bombers like the Ju87 Stooker, which required clear skies and precise bombing to achieve hits against maneuvering ships. American torpedo bombers like the Douglas TBD Devastator, were faster than the Swordfish, capable of 206 mph. But that speed made them vulnerable to fighters and required longer, more exposed attack runs.

At the Battle of Midway in June 1942, 41 Devastators attacked Japanese carriers without fighter escort. Only six returned, and they scored no hits. The slow Swordfish, attacking at night or in foul weather when fighters could not effectively intercept, achieved a survival rate that faster aircraft could not match.

German attempts to counter the swordfish threat focused on increasing anti-aircraft firepower rather than addressing the fundamental fire control problem. The Turpets, Bismar’s sister ship, carried an expanded anti-aircraft suite, including additional 20 mm and 37 mm rapid fire guns, but the fundamental issue remained.

Fire control systems designed for fast targets could not effectively track slow ones. The Shanho and Gnisau operating from Breast in 1941 and early 1942 faced repeated swordfish attacks. Whilst the aircraft rarely achieved hits against the heavily defended harbor, they forced the battleships to remain in port or sorty only with extensive air cover, negating their value as commerce raiders.

The channel dash of February 1942 when both ships and the Prince Yugen sprinted through the English Channel to return to Germany saw Swordfish from RAF Coastal Command launch a desperate attack in broad daylight. All six aircraft were shot down with no torpedo hits achieved, demonstrating that the Swordfish was no miracle weapon in unsuitable conditions.

Its strength lay in operating when and where enemy defenses were weakest, exploiting weather, darkness, and the limitations of fire control technology. The impact and legacy of the Swordfish extend far beyond the headline grabbing sinking of the Bismar. The aircraft remained in frontline service until the end of the war, long after contemporary wisdom suggested it should have been retired.

Its final major action came in 1945. still hunting yubot in the Atlantic. The lesson it taught was about asymmetric warfare, exploiting enemy weaknesses rather than matching their strengths. The Bismar’s loss forced Germany to adopt a more cautious posture with its remaining capital ships. The Turpits spent most of the war hiding in Norwegian fjords, venturing out only rarely, eventually destroyed by RAF Lancaster bombers carrying Tallboy earthquake bombs.

In November 1944, the Shanho was sunk by HMS Duke of York and accompanying destroyers off Norway’s North Cape on the 26th of December 1943 after being slowed by torpedo hits from destroyers. The Gnisau was damaged by RAF bombing in Keel and eventually scuttled. Germany’s surface fleet built at enormous cost achieved relatively little in part because the threat of obsolete British bipplanes forced them into defensive postures that negated their offensive potential.

The Swordfish influenced postwar aviation in unexpected ways. Its success demonstrated that slow, stable platforms had value in naval warfare, particularly for anti-ubmarine work where loiter time and sensor operation mattered more than speed. Modern helicopters fulfill a similar role, flying slowly over water, hunting submarines with sonar and torpedoes.

Surviving examples of the swordfish can be seen at museums including the Imperial War Museum Duxford, the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yilton, and the Royal Navy historic flight maintains airworthy examples that still fly at displays. Each one represents a triumph of pragmatic engineering over theoretical elegance. A reminder that wars are won not by the most advanced technology, but by the most effectively applied.

It is 27th May 1941 and somewhere on the Atlantic floor, the Bismar rests in darkness. Her guns are silent. Her crew are gone. The rudder that jammed at 12° to port still points uselessly into the black water. The torpedo that struck her stern was not a wonder weapon. The aircraft that delivered it was not a technological marvel.

What made the combination devastating was the simplest of tricks. Flying so slowly, so low, and so unexpectedly that the enemy’s sophisticated defenses became liabilities rather than assets. Germany built battleships to rule the seas. Armored fortresses equipped with the most advanced fire control systems, the most powerful guns, the strongest steel.

Britain built fabriccovered biplanes held together with wire and powered by engines that belonged in the previous decade. One approach cost billions of Reichkes marks and years of industrial effort. The other cost thousands of pounds and could be assembled in a factory in Hayes Middle Sex. The battleships are at the bottom of the ocean.

The biplanes are in museums preserved as examples of the most improbable success story in naval aviation history. The British did not outbuild Germany. They did not out armor her. They outthought her, exploiting a vulnerability so fundamental that German engineers never imagined it needed addressing. You cannot shoot what you cannot track.

And you cannot track what moves too slowly for your systems to follow. The Swordfish turned Germany’s best battleships into floating coffins. Not despite being obsolete, but because of it. Sometimes the slowest aircraft wins the race and sometimes the oldest weapon delivers the killing blow. The Atlantic remembers the ocean keeps its secrets, but the lesson remains.

In war, sophistication is no substitute for simply understanding what your enemy cannot defend against.