We are accustomed to thinking that there was a clear moral divide in World War II. There were the Nazis with their death camps and gas chambers. And there were the allies, the liberators who brought civilization and humanism to Europe. The British army was particularly proud of its image as gentlemen at war, observing the rules of fair play, even in hell.

But in 1944, this image was shattered by the armor of a single machine. A weapon so cruel that German officers called it unbritish and considered it a war crime. A weapon that turned its operators into suicide bombers. Captivity was out of the question for them and execution on the spot became the [music] unspoken norm.

This is the story of Churchill Crocodile, a tank that the British created by stepping on their own pride. A machine that solved problems not with tactics, but with primitive terror. And to understand why a nation of gentlemen decided to burn their enemies alive, we need to go back 2 years to a beach littered with corpses, where old British tactics [music] died along with thousands of soldiers.

On August 19th, 1942, the Allies descended on DEP as part of Operation Jubilee, a dress rehearsal for the future invasion of Europe. Among the 6,000 paratroopers and 58 tanks, three experimental vehicles named Boore, Beetle, and Bull landed on the shore. These were Churchill Oaks, the [music] British’s first attempt to combine heavy armor with flamethrower weapons.

And the war tested their strength in the first minutes of battle. The first tank sank [music] before reaching the shore. The landing ramp was lowered too early, and the 40tonon vehicle slipped into the straight 100 m from the beach. The second lost its flamethrower fuel tank when it hit the coastal pebbles. The third broke its track and came to a standstill at the water’s edge.

None of them accomplished their mission, but the crews continued fighting until the end of the day, turning the immobilized [music] vehicles into firing positions. All three tanks remained on DeF Beach, but the disaster [music] was even greater. Of the 58 Churchill tanks sent against the German fortifications, not a single one returned.

The concrete bunkers of the Atlantic Wall proved invulnerable to standard weapons, and the British command realized the obvious. To break through Hitler’s defenses, they needed weapons capable of reaching the enemy where shells could not. Behind concrete walls, in the slits of embraasers, [music] in the winding trenches where infantrymen died before they could take a single step.

A few days after DEP, German newsre showed a beach littered with burnedout churchills. Gerbles called it a warning to all who dream of a second front. He was right about one thing. The Atlantic Wall could not be breached by standard methods. The question was whether there were any non-standard methods. The Atlantic Wall stretched for 2,400 km [music] from Norway to the Spanish border, a continuous chain of bunkers, pill boxes, and machine gun nests capable of grinding down any landing force.

Tank shells left only potholes in the reinforced concrete. Infantry perished at the embraasers under heavy fire. [music] And the leaf boy hand flamethrowers with which the assault groups were armed had a range of only 35 m, a suicidal distance if machine guns were firing at you. 10 seconds of fuel behind you and almost certain death on approach to [music] the target.

The Oil Warfare Department, a secret agency headed by Sir Donald Banks, created back in 1940 to turn British oil reserves into a defensive weapon, had been looking for a solution for 3 years. Its engineers mounted flamethrowers on trucks, light Bren [music] carriers, and even ships.

The most promising seemed to be the Katrris, a flamethrower mounted on a heavy truck chassis capable of shooting flames 100 m. It looked impressive in tests. In practice, it turned out to be a deadly trap [music] for its own crew. The thin plating could not even withstand rifle bullets, [music] and the fuel tank turned the machine into a funeral p at the first hit.

The problem [music] was fundamental. In order to carry enough fuel for serious combat, the vehicle had to have armor [music] capable of withstanding return fire. And in order not to become a defenseless target after using up its fire mixture, it had to retain its main armament. There was simply no vehicle in the British arsenal that could meet these requirements.

By the beginning of 1943, the British had tried everything. [music] flamethrowers on trucks, on transporters, on ships. Nothing worked. To break the deadlock, they needed more than just an engineer. They needed someone capable of reinventing the very [music] concept of a flamethrower tank. And such a person existed, except that the army had kicked him out two years earlier for his unbearable personality and habit of telling generals they were idiots.

The solution came from a man whom the British army had twice thrown out and [music] twice brought back because they couldn’t do without him. Major General Percy Hobart had a reputation as both a genius and an unbearable personality with the latter regularly outweighing the former in the eyes of his superiors.

His sister was married to Montgomery, [music] but family ties did not help his career. They harmed it. Two powerful people under one family roof generated more conflicts than alliances. In 1943, Churchill personally pulled Hobart out of another disgrace and entrusted him with a task that no one else could be trusted with, to create an arsenal of machines capable of breaking through the Atlantic Wall.

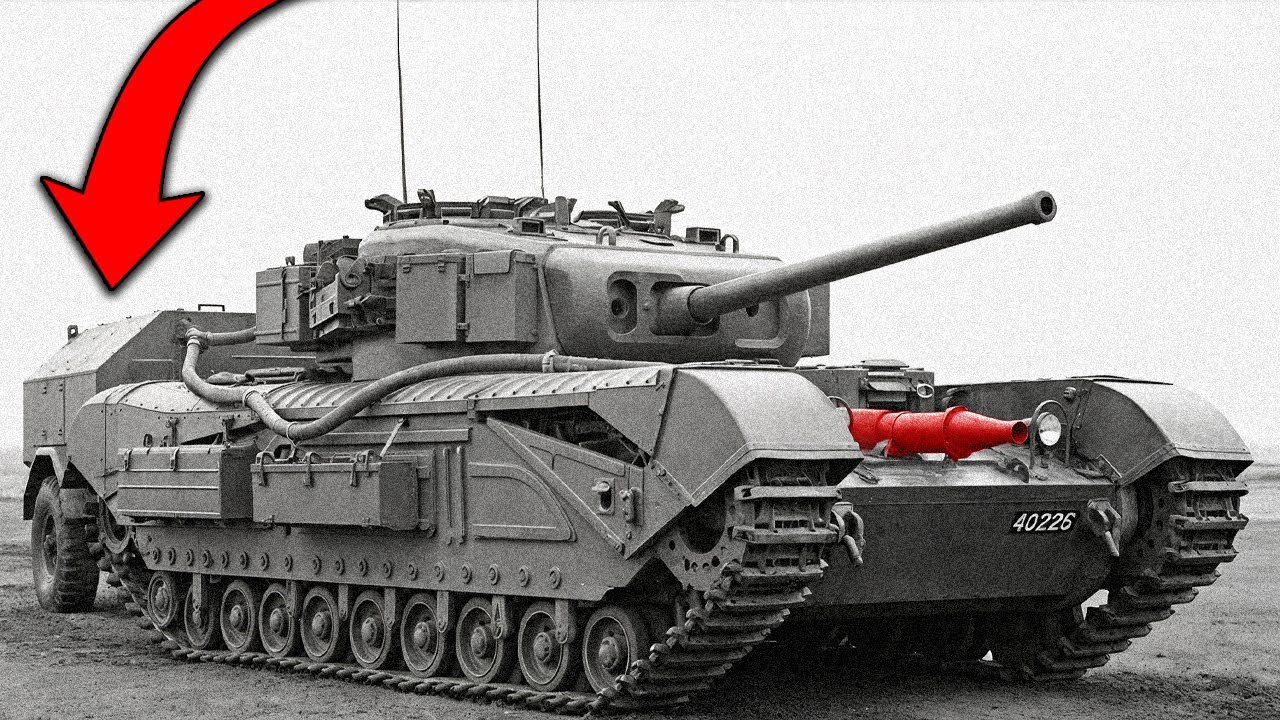

The soldiers would call them Hobart Circus. Officially, it was the 79th [music] Armored Division. In the fall of that year, Hobart was shown a prototype flamethrower tank at the testing ground, a clumsy contraption made from a Churchill tank, an [music] armored trailer, and a system of pipes running under the chassis.

The general watched as the machine crawled into position. A spark flashed from the nozzle and a jet of flame shot out with a guttural roar, reaching a 100 meters and covering the training bunker with a solid wall of fire. In a few seconds, the concrete box turned into a furnace. Hobart had seen enough. He immediately put pressure on the Ministry of Supply and the project, which had been bogged down in bureaucratic approvals for years, was given the green light.

The crocodile became the crown jewel of his freak show [music] and its design reflected the brutal logic of engineers who had to solve an [music] unsolvable problem. They moved the fuel outside the tank into a six-tonon [music] armored trailer on two wheels that could hold 400 gall of thickened fire mixture.

This substance had nothing in common with ordinary gasoline. It adhered to concrete, metal, and human skin and continued to burn even in water because it contained an oxidizer within its structure. Five cylinders of compressed nitrogen forced it through an armored pipe laid under the tank’s bottom to the flamethrower in the front plate, and the jet shot 140 m, ejecting 18 L/ second.

81 second volleys were enough to turn any fortification into hell. But the crocodile’s main advantage was not its flamethrower. The tank retained its standard 75 mm gun and remained a fullyfledged combat vehicle. The British had acquired a weapon against which there was no defense. Concrete melted, trenches [music] turned into furnaces, and garrisons became living torches.

But every advantage requires a sacrifice, and those who volunteered to operate these machines would soon learn why the Germans would hate them more than any other enemy in this war. Every advantage came at a price, and the Crocodile’s designers knew this better than anyone. The trailer, 6 1/2 tons on two wheels behind the tank, became an obvious target for any anti-tank weapon.

Its armor could withstand bullets and shrapnel, but not shells. The crews learned to maneuver so as to cover the trailer with the vehicle’s hull. But in the chaos of battle, this was not always possible. One lucky shot and 1,500 L of flammable mixture turned into a funeral p. The crocodile’s technology was considered so secret that damaged vehicles were ordered to be destroyed at any cost.

Even with air [music] strikes on their own if there was no other way, it was unacceptable for the trailer or flamethrower system to fall into German hands, and this order was strictly enforced. But it was the crews who paid the highest price. Those who sat in the crocodile understood the unspoken rules of the game from day one.

The Germans hated [music] flamethrowers with a fury that went beyond ordinary military cruelty and captured tankers were shot on the spot. This was documented and was no secret. The commanders did not hide the truth from the newcomers. It was better to know in advance than to harbor illusions. Among the crocodile crews, there was an unspoken [music] rule.

The word capture was not spoken aloud. It was not out of superstition. There was simply nothing to talk about. The people who drove these machines into battle knew that for them there was only victory or death. The war left them no third option, and they accepted this with the grim calm of professionals doing a [music] job that few are capable of.

On June 6th, 1944, the crocodiles of the 141st Royal Armored Regiment landed on the coast of Normandy in the first [music] wave of the landing. It was the vehicle’s baptism of fire, and it did not disappoint. In the first weeks of fighting, the crews developed tactics that turned the flamethrower from a weapon of destruction into an instrument of psychological warfare.

The crocodile would approach a fortified position at firing range and deliver a short demonstration volley, not at the embraaser, but nearby so that the garrison could see what awaited them. The jet of flame roared like a jet engine and struck a 100 meters away, leaving a strip of burning earth behind it.

If the defenders did not raise a white flag, the next volley was fired into the defender’s position. Often the first volley was enough. However, the real demonstration of its capabilities took place 3 months later on the other side of France at the walls of a city that the Americans could not take. breast held out for 5 [music] weeks. 40,000 German soldiers under the command of paratrooper general Herman Bernhard Ramka, a veteran of Cree and North Africa and one of the most stubborn commanders in the Vermacht, turned the old French forts into impregnable

fortresses. Hitler personally ordered Ramka to hold out until the last bullet and he carried out the order with grim diligence. American artillery and aircraft pounded the fortifications day after day, but the garrisons continued to resist. General Bradley requested assistance from the 79th Division, and Squadron B arrived at breast [music] with 15 crocodiles.

Fort Mont towered over the surrounding area like a concrete fist, a 12 m wide moat, 18 m high walls, and a garrison that repelled assault [music] after assault. Captain Cobden did not wait for headquarters to agree on the next plan of attack. He climbed out of his Churchill under mortar fire and crawled [music] forward to assess the possibility of the moat and the approaches to the fort with his own eyes.

A few minutes later, he returned with a route in mind and led his platoon to the gates, which still seemed impregnable. The British worked methodically. Sapper tanks broke through the concrete. Crocodiles flooded them with fire, and the flames flowed inside along the corridors, finding every crack, every embraasure, every turn.

Some garrisons surrendered after the first demonstration volley. those who had heard from their surviving comrades what the roar of the crocodile behind the wall meant. On the third day, Ramky personally fired the last shell from the gun, a theatrical gesture that changed nothing. Following him, the remnants of the garrison came out of the fort’s [music] gates with their hands up.

In a week, 40,000 German soldiers surrendered near Breast, and a significant number of them preferred captivity after seeing or hearing what flamethrower tanks were capable of. The Germans learned quickly after the first clashes with the crocodiles. Instructions were issued to Vermach units. Tanks with a distinctive silhouette, the squat Churchill pulling an angular two- wheeled trailer were to be destroyed first at any cost by any means available.

Anti-tank guns concentrated their fire on these vehicles, ignoring other targets. The trailer became their Achilles heel. One successful hit was enough to ignite 1,500 lers of fuel mixture at once, turning the tank and its crew into a funeral p in the middle of the battlefield. But fear did not only breed tactical adaptation.

It bred hatred, and hatred demanded an outlet. Soldiers who saw their comrades burned alive in bunkers and trenches [music] had no desire to take prisoners. The crews of disabled crocodiles who were [music] unable to escape or die with their vehicles were shot on the spot. This was documented by British intelligence and was no secret to those who served in the flamethrower units.

Revenge for burned comrades became an unspoken norm. Fear melted into cruelty that no one could control. Even among the British themselves, the crocodile evoked mixed feelings. The German accusation of unbritishness hit the mark more accurately than one would like to admit. Burning people alive, even enemies, even in battle, contradicted something deep in the self-awareness of a nation that had built its identity [music] for centuries on ideas of fair warfare and rules that could not be broken. But the war of 1944

knew no rules and those who wanted to win it could not afford the luxury of doubt. In May 1945, the crocodiles of the seventh Royal Tank Regiment were given a task for which there were no textbooks or regulations. Bergen Bellson, a liberated concentration camp where 60,000 living skeletons lay among 13,000 unburied corpses.

Typhus spread at a catastrophic rate, claiming 500 lives a day, even after the arrival of the Allies. Doctors and nurses did everything they could, but the disease was embedded in the barracks themselves, in the walls, in the floors, in every crack of the wooden buildings. The only way to stop the epidemic was to destroy the source of the infection.

The crocodiles burned the camp to the ground. Barracks after barracks, methodically and ruthlessly, they burned the typhus out of Bergen [music] Bellson, not as a weapon of war, but as a tool to save those who were still alive. It was [music] the last job for which the flamethrower tanks were intended in Europe.

250 crocodile kits were kept in reserve for the invasion of Japan, but the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki made that invasion unnecessary. The machine sat in storage for several years until 1950 when they were sent to Korea. The last war for the last dragons. By 1951, the crocodiles were finally decommissioned, and the era of flamethrower tanks ended as mundane as the service of any obsolete weapon.

Today, one crocodile stands on the parade ground of Fort Montberry embraced, a gift from Queen Elizabeth II to the city it once helped liberate. Others are scattered in museums from Bobington to Kubanka. Silent exhibits behind fences past which tourists pass without lingering. Armored relics of an era when war had not yet learned to be ashamed of its own face.

154 people were killed [music] by fire. 5,000 who surrendered without a fight. These figures from Normandy still raise a question to which there is no easy answer. what to call a weapon that saved more lives than it took, including enemy lives. Today, the crocodile stands behind a velvet barrier [music] in the Boington Museum, and school children run past it to the tiger in the next hall.

It looks more impressive. A few seconds at the name plate, a quick photo on a phone, and on they go. No one lingers. No one smells the stench that permeates the crew’s overalls. No one hears the roar that made the garrison surrender. The Germans called this machine unbritish and shot its crews as war criminals.

The British responded with fire that neither concrete trenches nor pleas for mercy could save them from. Both sides believed they were right. Both sides were people who war had forced to cross a line that existed only in peace time. Here’s what’s interesting. Flamethrowers were banned. Conventions, protocols, international agreements.

Humanity decided that burning people alive was unacceptable. [music] But thermobaric bombs which burn the oxygen in the lungs remain in arsenals. Napom was poured onto the jungles of Vietnam 20 years after Normandy. And phosphorus shells are still used today. They’re just called illumination shells. Maybe it’s not about the weapon itself.

Maybe it’s about how close you see the person you’re killing. The crocodile worked at a distance of 100 m. Its crews looked through viewing slits [music] at what their weapons were doing. Today the drone operator sits on another continent and for some reason this seems more acceptable to us.

So what is more frightening? Fire that can make the enemy surrender or a missile that leaves no such choice?