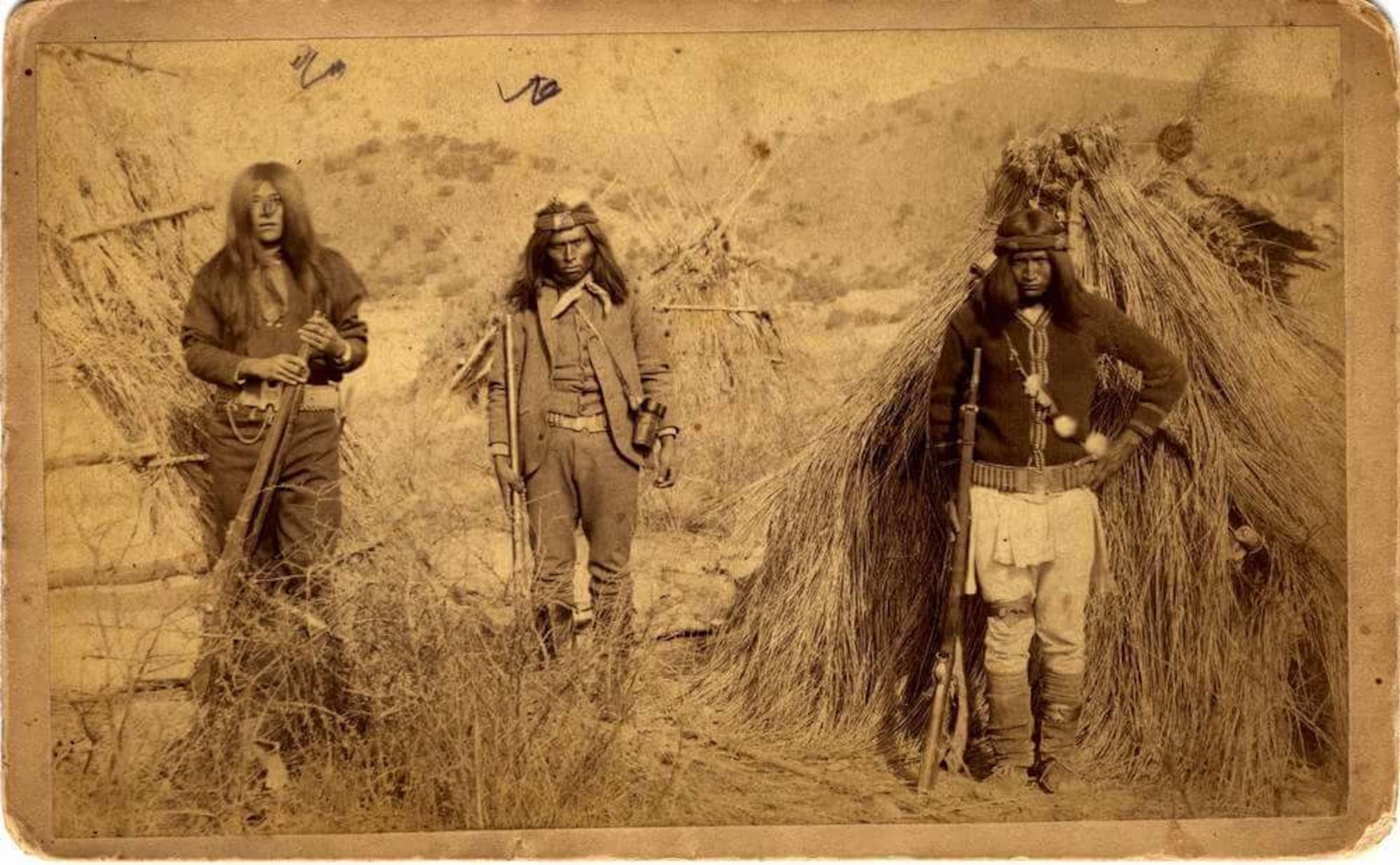

The Shadow War: Inside the Secret Apache Units the U.S. Government Buried for 80 Years

History is often written by the victors, but it is also edited by them. For over eighty years, a specific chapter of the American experience in World War II has been meticulously suppressed, hidden away in classified vaults across Fort Huachuca, Andrews Air Force Base, and the National Archives. It is a story not of traditional battlefield glory, but of the weaponization of ancient cultural practices, the systematic destruction of the human psyche, and a military program so dark that it challenged the very moral foundations of the nation it sought to protect. This is the history of the Shadow War Initiative—the secret recruitment and deployment of Apache warriors who were trained to become “ghosts” on foreign soil.

The Midnight Telegram

On the morning of December 8, 1941, less than twenty-four hours after the smoke began to clear from the wreckage of Pearl Harbor, a telegram arrived at the San Carlos Apache reservation in Arizona. It was standard War Department issue, but its request was unprecedented: the immediate presence of tribal council members at Fort Huachuca for a matter of “national security and cultural preservation.”

By nightfall, twelve Apache elders had made the journey through the Sonoran Desert. They were led into a windowless concrete room, illuminated by a single bulb. Across from them sat three men in Army uniforms, their name tags removed and rank insignia stripped away. The officer in charge, known to history only as “The Colonel,” placed a leather folder on the table. He didn’t open it. Instead, he made a proposal that would never appear in any official war record: he wanted the Apaches to help win the war by teaching American soldiers the art of psychological terror.

Joseph Tissosce, the tribal chairman, studied the officer. His response, recovered from a single declassified fragment decades later, set the tone for the nightmare to follow: “Our grandfathers knew how to make an enemy afraid of the dark. If you want us to teach your soldiers that art, you must understand it comes with a cost. Once a man learns to move like the wind and kill like the mountain lion, he does not easily return to being a man who sleeps peacefully.”

Creating the Ghosts: The Box Canyon Facility

By January 1942, the program had its first volunteers. They were taken to a newly constructed facility thirty miles northeast of Fort Huachuca, situated in a box canyon that had once been traditional Apache hunting grounds. The location was chosen to tap into something primal. Of the 147 men who reported for training, only 63 would finish. The rest simply disappeared from military records, their families receiving vague telegrams about “classified transfers.”

The training was unlike anything in conventional boot camps. It combined ancient Apache guerrilla tactics with emerging psychological warfare techniques. The men were taught the “fear walk”—the art of stalking an enemy position for hours, moving objects, creating unidentifiable sounds, and leaving cryptic markings to suggest that something inhuman was passing through. The goal was to break the enemy’s will long before the physical confrontation began.

Lieutenant Robert Chen, one of the few non-Apache officers allowed to observe the training, wrote in a 1942 journal entry: “Today I watched something that made me question whether we are the good guys in this war… By the time you actually engage, the enemy is already psychologically defeated. They are fighting ghosts, and ghosts cannot be killed.”

The Pacific Theater: The Silent Ones of Mindanao

The first deployment occurred in June 1942, with twelve men inserted behind Japanese lines in the jungles of Mindanao, Philippines. While their official mission was intelligence gathering, their reality was “hyper-aggressive psychological operations.” They conducted targeted assassinations and psychological sabotage designed to create maximum terror.

The impact was immediate and devastating. The diary of Lieutenant Yamamoto Kenji, a Japanese officer recovered after the war, describes an encounter where twenty of his men were found dead without a single shot being fired. “We found Sergeant Nakamura hanging from a tree at dawn… no blood on the ground beneath him. Around the tree were markings we could not identify… my commanding officer has ordered us to abandon this position. The men are terrified. They speak of demons and spirits.”

What Yamamoto didn’t know was that only two Apache soldiers had been responsible for the collapse of his entire battalion. They used traditional stealth combined with subsonic frequency devices and chemical compounds designed to induce hallucinations and paranoia when absorbed through the skin.

The Ardennes and the Ghost Soldiers of the Forest

As the war progressed, these shadow units were deployed to every major theater. In the frozen forests of the Ardennes during the Battle of the Bulge, a German battalion reported being systematically hunted by “ghost soldiers.”

A letter from Oberleutnant Hans Richter to his wife described the horror: “Marta, I do not think I will see you again. We are being hunted by something that defies explanation… The Americans have unleashed something from the old world… I saw one of them just a glimpse in the moonlight. He was covered in markings and his eyes reflected the light like an animal’s. I know now why our men are deserting. It is not cowardice; it is survival instinct.”

Three days later, the entire German battalion surrendered without a single direct engagement—the first time in the war such an event occurred. The intelligence reports from the surrendering troops were immediately classified and removed from the normal chain of documentation.

The Cost of the Shadow: Post-War Disappearances

As the war ended, the military faced a problem it hadn’t anticipated: the men they had transformed into shadow warriors couldn’t simply “turn off” their conditioning. They had been psychologically altered to operate outside all rules of civilized combat.

The solution was cold and pragmatic. Of the 237 men who completed the training, only 68 appear in any post-war military records. The rest vanished. Their families were told they died in combat, but no bodies were ever returned, and no graves were ever marked. They remained ghosts by design.

The few who did return were sent to a secret rehabilitation facility in the mountains of New Mexico. A surviving letter from Thomas Naich to his brother in 1946 tells a chilling story: “They tell us we are being helped, but this place is a prison… I think they are trying to make us forget, but you cannot forget what you have become… They want to erase what they created. If you receive notice that I have died, do not believe it.”

Naich’s official death certificate states he died of pneumonia. No hospital records confirm his presence at any facility. He was twenty-six years old.

The Cold War and the “Night Wind” Continuation

The program didn’t end with World War II; it simply went deeper underground. The onset of the Cold War created a new demand for operatives who left no “fingerprints.” Between 1948 and 1963, a continuation program code-named “Night Wind” recruited over a hundred additional Apache operatives. These men were deployed to Korea, Vietnam, Guatemala, and Iran.

In Korea, stories of the “wind that kills” terrified Chinese and North Korean troops. In Vietnam, Green Beret Captain Raymond Teller reported finding an entire Viet Cong company—120 men—dead in a clearing with no bullet wounds or signs of combat. “Every single one of them looked absolutely terrified,” he wrote. “Their eyes were wide open, their faces frozen in pure horror.”

By the 1960s, the technology had evolved. The military was testing “Whisper Agent,” a chemical compound that induced acute anxiety and auditory hallucinations, and acoustic weapons that produced subsonic frequencies capable of inducing cardiac arrest.

The Legacy of the Shadows

The reservations in Arizona and New Mexico remain places of collective trauma. Elders speak in hushed tones about the men who went away and the ones who came back “changed”—men who couldn’t sleep indoors, who spoke languages no one recognized, and who seemed to exist between two worlds.

In 2004, a former operative using the pseudonym “David Knighthorse” briefly came forward, describing an underground facility in the Four Corners region where he was taught to tap into “ancestral memory” through drugs and sensory deprivation. His story was quickly scrubbed from the internet, and he hasn’t been heard from since.

The Shadow War Initiative was effective—perhaps too effective. It proved that the most powerful weapon in any arsenal is not a bomb or a bullet, but fear. By weaponizing ancient traditions and modern science, the U.S. government created a force that could win wars in the shadows, but it did so at the cost of the souls of the men who served.

As we look back at the 80th anniversary of these events, the files remain largely sealed, and the “Heritage Warrior” budget items continue to appear in unredacted slips, suggesting the program may still exist in some form today. The ghosts of the Shadow War still walk, waiting in the classified darkness for a history that may never be fully allowed into the light.