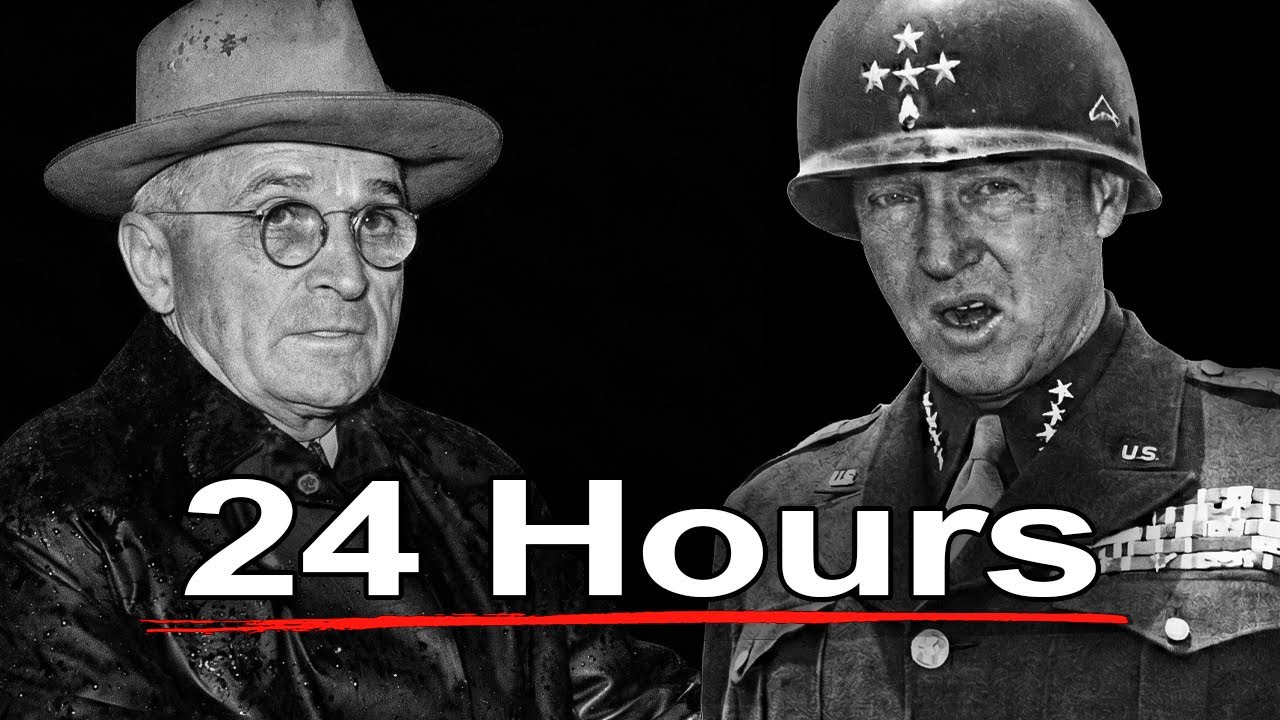

July 1945, President Harry Truman sat in his private quarters after a long day negotiating the fate of postwar Europe with Stalin and Churchill. He opened his diary and wrote about the American general who was causing him the most trouble, not in Germany, in the newspapers. Truman wrote that he had to use every bit of credit he had to keep from telling Patton what he thought of him.

He grouped Patton with Kuster and MacArthur, glory hounds who had no regard for the men they led. You can almost feel the pen digging into the paper. This wasn’t a president analyzing a subordinate. This was a man venting pure, unfiltered rage. In another entry, Truman wondered how America could produce steady, reliable leaders like Eisenhower and Bradley, while also producing failures like Patton. failures.

The general who had just liberated France faster than anyone thought possible. The general whose third army had broken the German line at the bulge. A failure. This wasn’t military criticism. [clears throat] This was personal hatred. And it would shape everything that happened next. To understand why Truman feared Patton, you have to understand how insecure Truman’s position was in 1945.

Truman had been president for less than 4 months. He had inherited the office when Roosevelt died in April. He was the understudy who had been shoved onto the stage, governing in the shadow of a dead giant, knowing that half of Washington was whispering that he wasn’t up to the job. His political footing was fragile.

The Democratic Party establishment viewed him as a placeholder. Republicans smelled blood. The 1948 election was already being discussed and Truman was not guaranteed his party’s nomination. Then there was Patton. George Patton was the most famous general in America. His face had been on the cover of Time magazine.

News reels showed his tanks liberating France. He was quotable, theatrical, and beloved by millions of Americans who saw him as the warrior who won the war. And powerful voices were urging Patton to run for office. In letters to his wife, Beatatrice, Patton discussed how to use his influence to change the course of history.

His name was being floated by conservative columnists as a potential presidential candidate, a general who could speak bluntly about the communist threat, a hero who could challenge the politicians who were giving away Eastern Europe. Truman understood what a patent presidential campaign would look like. It would be built on attacking everything Truman stood for.

the cooperation with Stalin, the demobilization of American forces, the trust in the United Nations. Patton wouldn’t just be a rival candidate. He would be an existential threat to Truman’s entire foreign policy. Truman faced an impossible situation. He couldn’t fire Patton outright. Firing America’s most celebrated general would create a political firestorm.

Republicans would accuse Truman of persecuting a war hero. Veterans groups would be outraged. The press would demand explanations. Worse, firing Patton would make him a martyr. A private citizen, Patton could say whatever he wanted. He could write books, give speeches, testify before Congress, run for president.

As long as Patton wore the uniform, he was subject to military orders. He could be told where to go, what to say, and who to talk to. The army could control him. But a civilian patent, [clears throat] uncontrollable. Truman needed Patton contained, not fired, not martyed, contained. The solution was elegant.

\

Keep Patton in Germany. Keep him in uniform. Keep him away from Washington, away from Congress, away from the American people. let him rot in obscurity until everyone forgot about him. By October 1945, the containment strategy was in place. Patton had been stripped of Third Army command and assigned to the 15th Army, a paper organization with no troops, no mission, and no purpose except writing historical reports.

For a man who lived for the roar of battle and the smell of diesel, this wasn’t a new assignment. It was a padded cell. They were burying the most dynamic leader of the war under a mountain of paperwork. If you’ve seen the previous episode on this channel, you know how Eisenhower engineered this exile. What that episode didn’t cover was what happened next, the travel ban.

Patton immediately requested permission to return to the United States. He wanted to see his family. He wanted to meet with officials in Washington. He wanted to address the American public. Every request was denied. The official reasons varied. Administrative needs in Europe, ongoing historical documentation, responsibilities that couldn’t be delegated.

But when you look at the timeline, these denied requests form a clear and systematic pattern. October 1945, Patton requested 30 days leave to return to the United States, denied. Eisenhower cited the need for Patton’s presence during the transition period. November 1945. Patton requested a transfer to help with the occupation of Japan. Denied.

The War Department said his skills were needed in Europe. Later that month, Patton requested a brief trip to Washington to consult with War Department officials. Denied, he was told to submit his recommendations in writing. Each denial came with a reasonable bureaucratic explanation. Taken individually, they seemed routine.

Taken together, they revealed a systematic effort to keep George Patton out of the United States. Patton understood what was happening. They were keeping him muzzled. As long as he remained in uniform in Germany under military authority, he couldn’t speak freely. He wrote to Beatatrice in late November that he was considering immediate retirement, but he worried anything he said afterward could be attributed to revenge.

Then he found a better solution. In late November 1945, Patton began telling his closest staff about his decision. It was a conversation held in hushed tones. The most famous general in the United States Army was essentially plotting a mutiny. He would request one more leave to return to America, a standard 30-day leave, nothing suspicious.

Once on American soil, he would submit his resignation from the army, effective immediately. The timing was critical. If he resigned while still in Germany, the War Department could delay processing the paperwork indefinitely. They could claim administrative issues. They could keep him in uniform and under orders for months.

But if he resigned after arriving in America, he would be a civilian within days, free to speak, free to travel, free to tell the American people exactly what was happening in Eastern Europe. Patton planned to spend January 1946 organizing a national speaking tour. He would visit major cities. He would address veterans groups.

He would testify before Congress if asked. He had already drafted the speeches. Among Patton’s papers were draft speeches for what he called his truth tour. The speeches were explosive. Patton planned to tell Americans that [clears throat] the Yaltta agreements had been a betrayal, that Roosevelt had given Stalin everything he wanted in exchange for promises Stalin never intended to keep.

He would describe Soviet atrocities in Eastern Europe, the mass deportations, the executions, the puppet governments being installed at gunpoint. He would reveal the dark reality of the occupation that his intelligence officers had documented. He would argue that the United States had won the war against Germany only to hand half of Europe to an enemy just as dangerous.

That American soldiers had died to liberate France while Stalin enslaved Poland. And he would call for immediate action. Confront the Soviets while American forces were still strong. Push them out of Eastern Europe before they consolidated control. Arm the resistance movements. fighting communist occupation. This wasn’t just criticism of Soviet policy.

This was a direct attack on everything Truman was trying to accomplish. If Patton gave these speeches, the American public would have turned against the White House overnight. The United Nations, the cooperation with Stalin, the post-war order, all of it would be under assault from America’s most famous war hero. Truman couldn’t allow that to happen.

In early December 1945, something unexpected happened. The War Department approved Patton’s leave request. 30 days in the United States beginning December 10th, 1945. Why the sudden reversal? The administration likely realized that denying him was becoming dangerous. Newspapers were starting to ask why America’s most famous general couldn’t visit his own country.

It was smarter to bring him close than to leave him angry in Europe. The logic was simple. They could manage Patton better in Washington than in Germany. If Patton came home, they could pressure him to retire quietly with full honors, or threaten consequences if he spoke out, a private meeting, a gentle reminder about his pension, a suggestion that public criticism would tarnish his legacy.

They didn’t know about the resignation plan. They didn’t know about the speeches. They thought they were bringing home a tired general ready to fade away. They were wrong. Patton scheduled his flight for December 10th. He spent December 9th packing his papers and preparing for departure.

He told his staff that by January he would be a civilian and then nothing could stop him from telling the truth. He had 24 hours left in Germany. December 9th, 1945. Patton decided to spend his last day in Germany on a hunting trip. At 11:45 a.m., his staff car was traveling near Mannheim. A US Army truck pulled out from a side road directly into their path. The collision was low speed.

Everyone else involved, the drivers, the passengers, even Patton’s chief of staff, walked away without a scratch. There were no enemy tanks, no artillery bargages, just a foggy road, a moment of bad luck, and a dull thud that accomplished what the entire German Vermacht never could. He lay paralyzed in the back seat 24 hours before his flight to freedom.

The speeches would never be given. The resignation would never be submitted. The truth tour would never happen. The one man who could have challenged Truman’s entire foreign policy was silenced on the eve of his escape. Patton lay paralyzed in a hospital bed for 12 days. His wife flew from America to be at his side.

Messages poured in from generals and soldiers around the world. From the White House, there was almost nothing. No presidential envoy visited Patton’s bedside. Truman sent a telegram to Beatatrice. official, bureaucratic, and utterly cold. No personal warmth, no acknowledgement of what Patton had done for the country.

When other generals faced medical crisis, presidents sent representatives. When political allies were hospitalized, Truman made public shows of support. For the man who had helped win the war in Europe, there was cold silence. While Patton lay fighting for his life, the government he served simply turned its back.

The contrast was noted by Patton staff, by military observers, by anyone paying attention. On December 21st, 1945, George Patton died from complications of his injuries. He was 60 years old. The official cause of death was pulmonary edema and heart failure. The real cause was a broken neck suffered in a freak accident on a quiet Sunday morning.

Within two years, everything Patton planned to warn Americans about came true. Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe became permanent. Communist governments were installed in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and East Germany. The Iron Curtain descended exactly as Patton had predicted.

Truman’s cooperation policy collapsed. By 1947, he announced the Truman doctrine, containment of Soviet expansion. The policy Patton had advocated [clears throat] in 1945, repackaged two years later. The Cold War lasted 45 years. Millions died behind the Iron Curtain. Trillions were spent on containment. and George Patton, [clears throat] the one man who had tried to warn America in time, died in a German hospital bed one day before his escape.

Whether the accident was truly an accident has been debated for decades. No evidence of conspiracy has ever been proven. The timing remains suspicious to anyone who knows what Patton was about to do. What’s certain is that Harry Truman got exactly what he needed. The problem had solved itself. The speeches were never read. The rallies never happened.

The storm that was about to break over Washington simply dissipated. And the general who saw the future was buried in Luxembourg, surrounded by the soldiers who had followed him across Europe, silenced forever.